All

“Cloud Walkers” Pairs Asian Video and Installation Artists with Architects, Speaking to “Climate, Imagination, and Hyperlinks Alike”

“Cloud Walkers,” an exhibition speaking to “climate, imagination, and hyperlinks alike,” opens in Seoul. Pairing Asian video and installation artists with architects, its contributors include Lawrence Lek, A.A. Murakami, Tromarama, and Samson Young. Curated by June Young Kwak, the show cultivates dialogues across mediums and epochs, as exemplified by the placing of LuYang’s hyper-digital DOKU Hello World (2021) in Đoàn Thanh Hà’s (traditional) Floating Bamboo House (image).

Gruesome Deaths of her Digital Avatars an Act of Black Joy and Freedom, Martine Syms Says

“Seppuku with a chef’s knife. Crippling, fatal allergies. Diarrhea so explosive she rockets into the sky like a rag doll, then dies from the fall. Then, somehow, she gets up and keeps walking.”

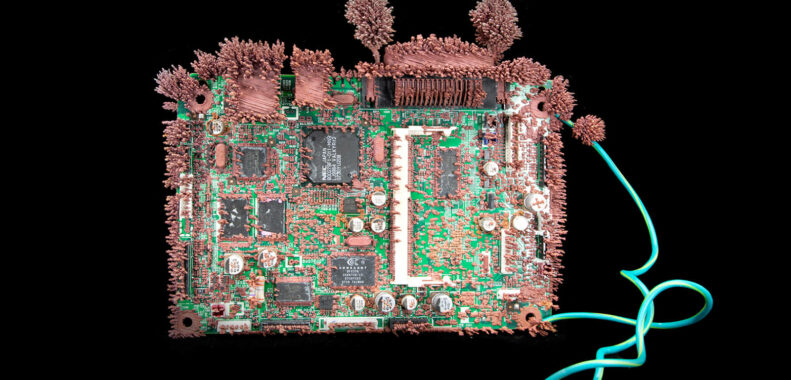

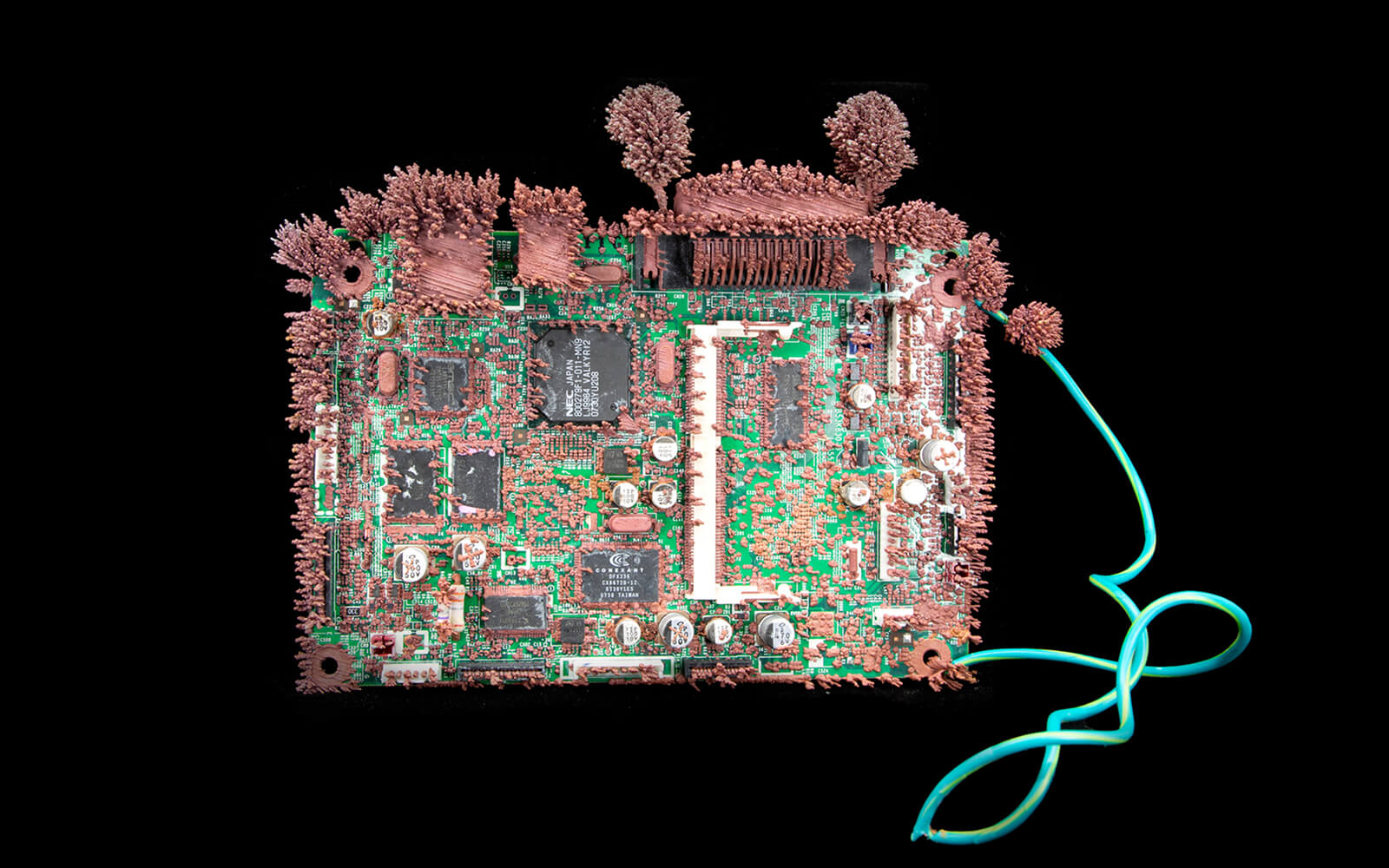

Imagining a future on a rapidly changing planet, “The New Earth” opens at Public Works, Chicago. Ten artists including Jeremy Bolen, Susan Goethel Campbell, Sam Rolfes, and Kat Jarvinen provide “a testing ground for addressing the preeminent issues of our time,” from AI to climate change. Jarvinen’s Feral Devices (2021, image), for example, disrupt waste cycles and assumptions about technological decay in search for “alternative realities for those things we throw away.”

Carbon Capture Won’t Fix the Climate Crisis, New Report Says

“Of the 13 projects examined for the study—accounting for about 55% of the world’s current operational capacity—seven underperformed, two failed, and one was mothballed.”

Featuring contributors including Ant Farm, Joan Jonas, and Jacques Cousteau, “Who Speaks for the Oceans?” opens in New York. Looking to challenge the legacy of “colonial, racialized, gendered, and terra-centric” ocean histories, the collected works foreground nonhuman perspectives and ecological responsibility. In Ursula Biemann’s video installation Acoustic Ocean (2018, image), for example, the artist-researcher documents her efforts to record the sonic ecology of marine life.

From 15th Century painting to NFTs: “Meta.Space: Spatial Visions” opens at Francisco Carolinum in Linz, Austria, gathering over 30 artists that examine “social, real, and imaginary space.” Next to the virtual worlds of late luminary Herbert W. Franke, for example, towers the site-specific ‘crypto sculpture’ by Alexander Grasser and Alexandra Parger. Open Architectures (image) is a wooden model of one of 50 community structures built collaboratively via interactive NFT.

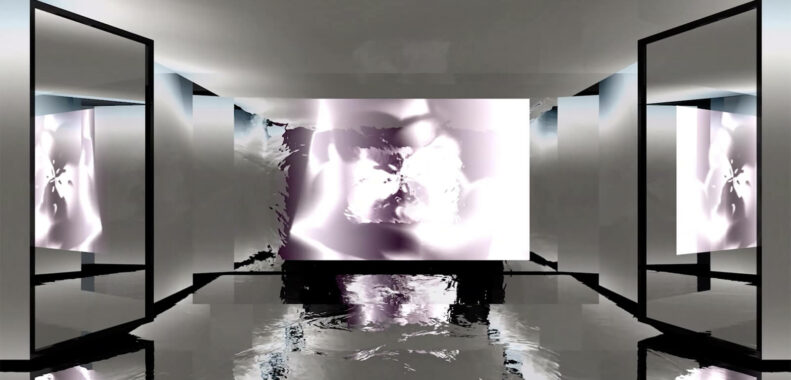

Leaning into notions of immateriality and the technological sublime, “Digital Art Waves” opens in Paris. Featuring artists including Kika Nicolela, Manfred Mohr, Quayola, and Nicolas Sassoon, whose contributions range from prints on paper and metal to video and NFTs. Sabrina Ratté, for example, reconstitutes her reflection-heavy 2016 CGI video piece Wintergarden, which “straddles the line between abstract architecture and an enclosed garden,” as an NFT (image).

August 2022

August 2022

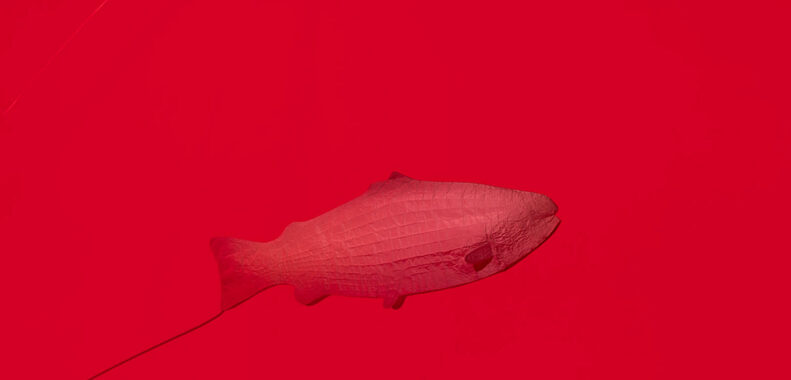

“Undamming Rivers,” a retrospective of food and environmental crisis-focused artist duo Cooking Sections, opens in Stockholm. The exhibition presents three iterations of the artists’ ongoing research on the impact of fisheries (image: Salmon: A Red Herring, 2020), as well as a new project exploring the removal of hydro dams. The curators note that both topics are poignant in Sweden, where widespread “salmon-breeding programs were established to compensate for habitat loss and migration obstacles.”

Bloomberg Journalists Quip about Irony of the Taliban’s Newfound Use of Internet Technologies and Platforms

“As much as they might aspire to go back to a medieval world, WhatsApp comes in handy.”

Korean artist duo Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho’s solo exhibition “Seoul Weather Station” opens at Art Sonje Center in Seoul, presenting two new works that tackle the planet’s collapsing ecosphere. The large-scale immersive installation To Build a Fire (2022) shows anthropocentric shifts from a nonhuman perspective—a four-legged robot—while Mobile Agora (2022) offers a participatory platform for critical climate conversations as part of the artist-run World Weather Network (WWN).

1960-1968

“What fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly.”

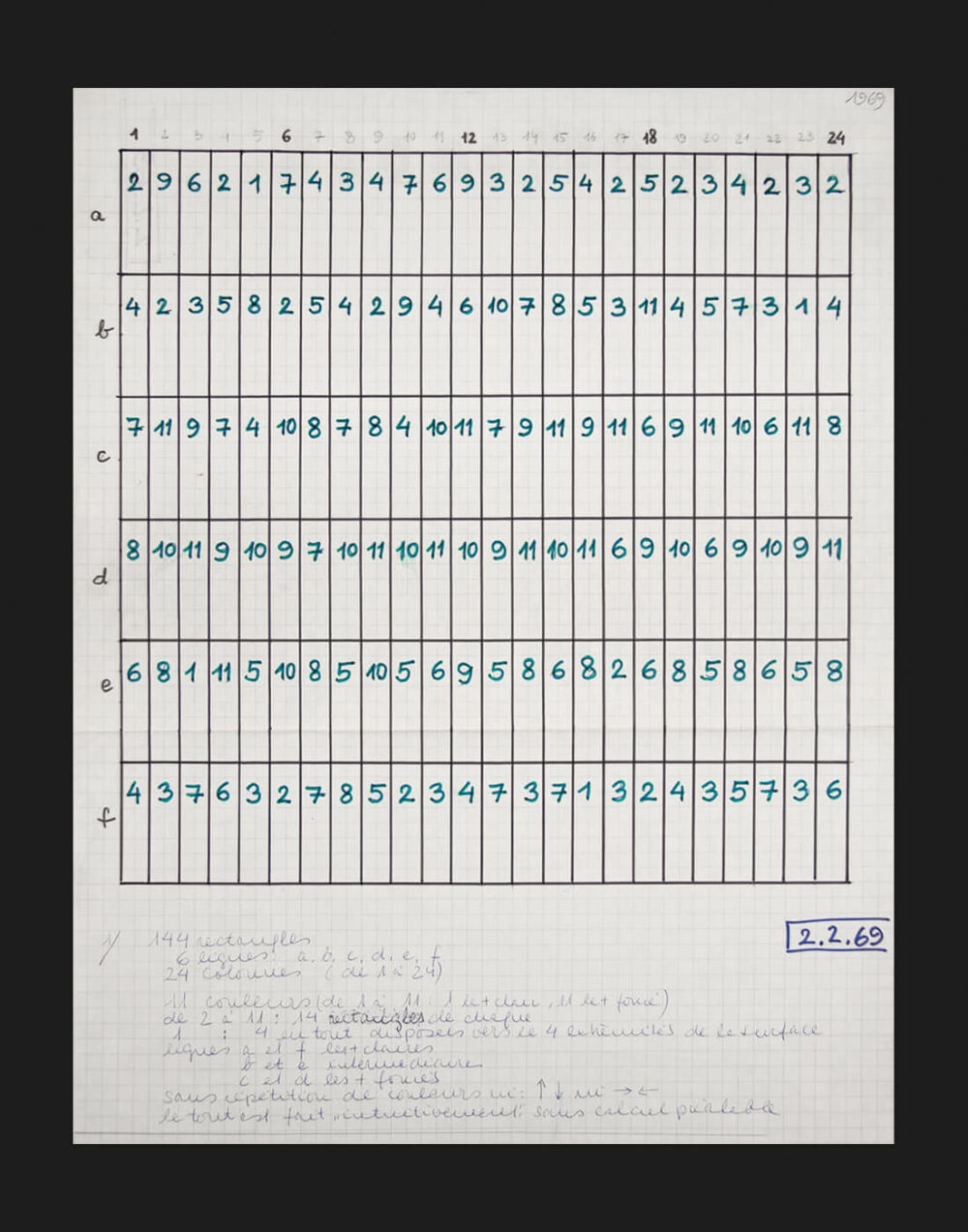

Before she had access to an electronic computer, Molnar worked with what she called the machine imaginaire, an imaginary computer or “a computer without a computer.”1 Molnar already knew what computers were, and what they could do, from books and magazines. While popular literature on computers focused on the looming question of artificial intelligence, the ‘electronic brain’ that might one day replace the human (a concern more rooted in science fiction than reality), what fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly, and on a scale infinitely larger than a human could do alone. Perhaps what she found most appealing was how the computer crunched numbers and made decisions without the interference of what Molnar called “cultural ready-mades”—bias that might influence a human’s decision-making process. The idea was this: while an artist might make decisions according to principles of “good form” or “good composition” they learned in art school, the computer started with a clean slate, and could therefore make ‘objective’ decisions.

In the early 1960s, as the electronic computer remained expensive and out of reach, Molnar emulated its objectivity by hand-writing simple ‘programs’ to generate series of pictures. The machine imaginaire algorithms used basic combinatorial mathematics, the area of math concerned with problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite or discrete system. Like a scientist conducting an experiment, she would alter only one variable or parameter in each iteration or variation, such as the choice of color or the angle of inclination of line segments. To make these changes, she often employed a rudimentary random-number generator: a roll of dice or the flip of a coin.

Molnar argues that her shift from machine imaginaire to machine réelle, in 1968, was not a radical break but rather a continuation of the same method with different tools. The digital computer, she wrote in Leonardo, was able to “facilitate the execution of this time-consuming procedure.”2 Using the computer was, put simply, more accurate and more efficient than executing programs by hand.

While 1968 is framed as such a pivotal moment in Molnar’s career, there are very few extant works from this period that bear visible traces of the computer. Skeptics might even say that her role as a pioneer of computer graphics has been exaggerated. Perhaps the reason Molnar’s earliest experiments are fuzzy to history is because we’re not looking for the right kind of evidence.

Let’s return to Molnar’s first encounter with the computer that I discussed in the context of her friendship with the composer Pierre Barbaud. On Barbaud’s invitation, Molnar visited the mainframe computer at Bull–General Electric in Paris. She went in wanting to experiment with random color distribution, but quickly found that they only had the hardware for monochrome graphics. So Molnar developed a program that generated a list of numbers (referred to as a listing in French), each corresponding to a color. Then, like a game of Paint By Numbers, she colored a grid of squares by hand according to these results. The image is not a plotter drawing; in its process, it is closer to the work of Jean-Claude Marquette, working across town in the other Groupe de l’art et informatique, who also used a listing to fill quadrille paper, which he then transposed to paint on canvas. Molnar, however, quickly tired of this method, and wouldn’t do it again. That was when she sought out the computer lab at Orsay, the Centre de calcul interrégional de calcul électronique (CIRCE), which had two different kinds of plotters; here, she could not only design pictures with computers but actually execute them computationally as well.3

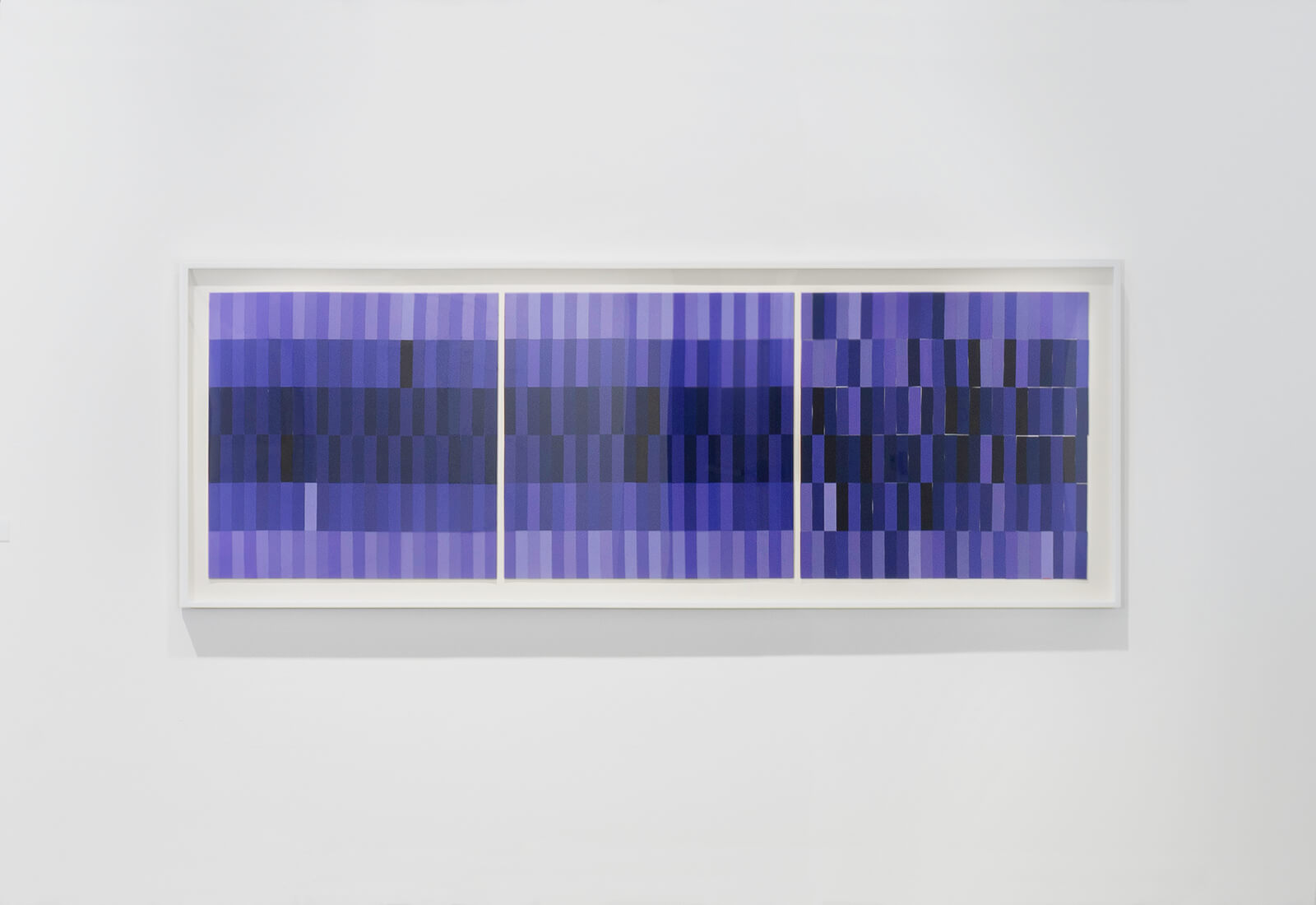

Molnar reminds us, however, that just because she started using a computer in the late 1960s doesn’t mean that she never made anything by hand again. It’s always been a back-and-forth for her—an idea that she crystalized in her recent artist’s book Main/Machine (Hand/Machine). David Familian, curator of the “Variations” exhibition, recently asked me about a triptych of collages in the show that Molnar made in 1969, 144 Rectangles. Did I know whether she used a computer here, or just a flip of a coin, to determine the placement of each purple rectangle? I shared Molnar’s anecdote about the listing—that some of her works, especially from this early period of computation, utilized the computer but were ultimately still handmade. It was a sort of “extension of the machine imaginaire,” David observed, “but instead of using a coin, she was using a computer.”

In other words, it would be reductive to divide Molnar’s work into pre- and post-computer art, with 1968 serving as a major turning point. The digital computer entered Molnar’s practice not with a bang, but gradually. We might even say that each step forward was followed by two steps back, until she figured out how the machine would best serve her interests. While Molnar has never presented herself as a ‘generative’ artist—this label is relatively recent, though not one she has explicitly rejected—the term feels especially appropriate here, for it acknowledges that an artist can work with systems and algorithms without necessarily using a particular technological tool. To focus on the generative is to focus on the artist’s process, which is what matters the most anyway.

References:

(1) Baby, Vincent. “Introduction à la « machine imaginaire » / Introduction to the ‘imaginary machine.’” In Vera Molnar: Pas froid aux yeux, edited by Vincent Baby and Francesca Franco. Paris: Bernard Chauveau Editeur, 2021.

(2) Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185.

(3) Conversation with the author, Oct 10, 2021

Chinese Metaverse Company Appoints Female Robot CEO

“We believe AI is the future of corporate management. Our appointment of Ms Tang Yu represents our commitment to truly embrace the use of AI to transform the way we operate our business, and ultimately drive future growth.”

Art Historian Zsofi Valyi-Nagy Unpacks Vital 1960s Period When Vera Molnar Started Using Computers to Make Art

“What fascinated Molnar about computers was more practical than speculative or futuristic. It was their capacity to compute, and to do so accurately, quickly.”

Out Now: Dan McQuillan’s “Resisting AI” Pushes Back against Algorithmic Governance

Dan McQuillan

Resisting AI

Copper Wire Theft Epidemic Now Hits EV Chargers

“They took the copper out of it. They actually cut it while it was charging somebody’s car.”

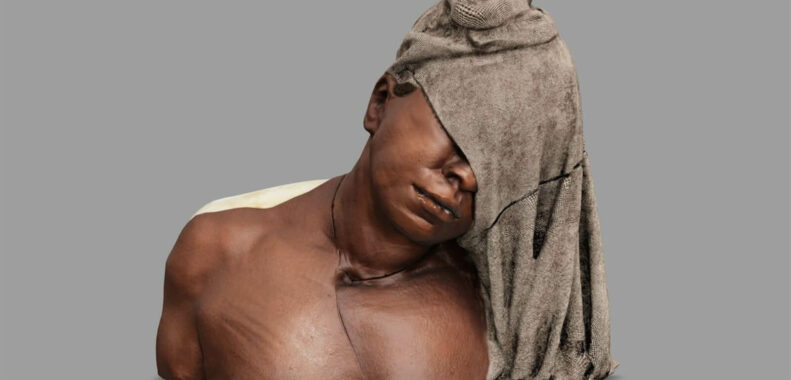

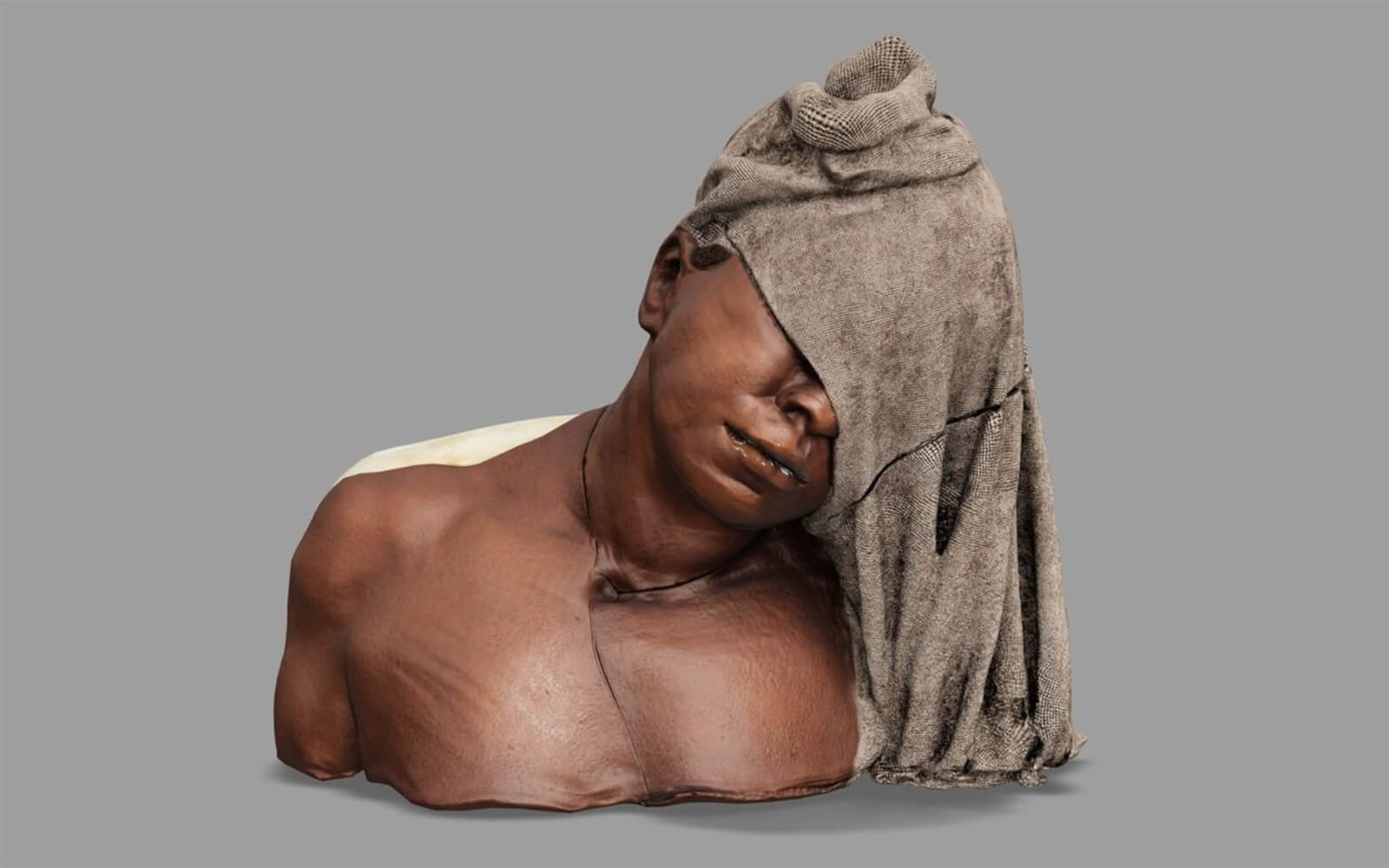

“Future Bodies,” a group exhibition examining corporeality and femininity in the digital age, opens in Amsterdam. Curator Anne de Jong brings together eight artists including Salomé Chatriot, Auriea Harvey (image: Pelops I, 2022), Lynn Hershman Leeson, Cassie McQuater, and Addie Wagenknecht, presenting positions from different generations. “New media has proven to be a feminist tool for artists to push the boundaries of identity, body, and space,” writes de Jong.

Elizabeth Preston Details How Scientific Care Standards “Privilege Animals with Backbones”

“Lab rats have rights … The same is true of scientists working with mice, monkeys, fish, or finches. These protected animals share one thing in common: a backbone.”

For almost a decade I’ve taught a class where we recreate artworks from the past in order to have a better understanding of the roots of computational art—each week we focus on a different practioner. Without fail I begin each semester with Vera Molnar’s work, because it offers us a chance to explore randomness and order but also, it’s a great class opener because her work is warm and ultimately about a kind of conversation with machines. Usually beginners get excited when they see the random() function; they create glitchy, frenetic and madening compositions where everything on screen rearranges itself every frame. But Vera’s work invites slowness and contemplation—it invites us to converse with randomness, to nudge a vertex over here, to delete a line over there, to push and pull at geometry until we agree or not, and begin again.

Zach Lieberman is a Brooklyn-based artist, researcher and educator. His projects have won the Golden Nica from Ars Electronica, Interactive Design of the Year from Design Museum London as well as listed in Time magazine’s Best Inventions of the Year. He creates artwork through writing software and is a co-creator of openFrameworks, an open-source C++ toolkit for creative coding and helped co-found the School for Poetic Computation, a school examining the lyrical possibilities of code.