← Explore

Provocation

Bodies as Systems; the Body in Systems

Speakers:

Laura Forlano, Louise Hickman

Profile:

Laura Forlano

Laura Forlano, a Fulbright award-winning and National Science Foundation scholar, is a writer, social scientist and design researcher. She is an associate professor of design at the Institute of Design, and affiliated faculty for the College of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology, where she is director of the Critical Futures Lab. Forlano’s research is focused on aesthetics and politics at the intersection between design and emerging technologies.

Curatorial Frame:

Louise Hickman and Laura Forlano explore how the knowledge, activism, and practices of crip- activists, crip-engineers, and scholars might reframe AI, and demand more from it. Both insist that if we look to these communities as inventive hackers of digital technologies, then we might find that we have never been short on imaginaries, or modes of interdependence. Hickman and Forlano will lead this session alongside a human live-captioner to show different kinds of skills, mutuality, and care possible within sociotechnical infrastructures. But, all technological infrastructures are prone to failure. What if we were, to take up technology as an affirmative kind of failure? Their provocations push for a deep consideration of difference, and a renewed focus on the role of the body in our built technological systems.

Soundbite:

“For four years from 2018 to 2022, I used one of the world’s first automated systems for delivering insulin in order to manage and control my blood sugar. I identify, research, and write as a disabled cyborg. I’m cyborg not because of my body being partly made of machines—the insulin pump and sensor system—but because of my knowledge of cyborg knowledges, practices, and politics.”

Laura Forlano, providing her backstory

Takeaway:

Forlano’s methods are worth underscoring. Her auto-ethnographic field notes blur autobiographical observations of health and wellness with the log of her maintenance regime. “This includes my use of synthetically produced hormones, insulin, my machine, an insulin pump, an assortment of digital and analog parts including sensors, tubing, charging cables, alcohol swabs, insertion devices, needles, and the like,” she notes.

Takeaway:

One issue with fields like User Experience and Interaction Design as—solutionist—they romantacize preferable outcomes. The disabled cyborg approach touted by Forlano sees “failure rather than perfection as the default setting” and recognizes that design oversights have tangible repercussions for edge-case users. “There may not be a single place to put the blame,” says Forlano.

Soundbite:

“Perhaps it’s not so unusual to talk about computational technologies as disabled. For example, it’s a common colloquial expression when talking about computing: your account has been disabled. But we rarely understand disability to be a property of both humans and machines.”

Laura Forlano, setting up a conversation about ‘crip human-computer interaction’ (HCI)

Soundbite:

“Often, I am not sure whether I am taking care of the devices or they are taking care of me. A turn towards a more relational more-than-human or posthuman subjectivity, that sees humans and machines as intimately entangled rather than discrete entities as they have been traditionally conceived.”

Laura Forlano, on interdependence

Precedent:

Pancreas at the Pool

In 2015, Forlano reached out to Sky Cubacub of Rebirth Garments, a fashion designer that creates QueerCrip garments with disabled people, in order to design a custom-made bathing suit that accommodates her insulin pump. “This piece allowed me to think more about the invisibility of diabetes as a disease in tandem with the visibility of the machines that I use to control my blood sugar,” she explains.

Soundbite:

“I was struck by the ways in which the choice of materials including cement, spandex, and rubber suggested an alternative narrative about computing in contrast to the shiny metal and glass of the latest line of mobile phones, tablets, and computers.”

Laura Forlano, on collaborating with Itziar Barrio on a series of sculptures

Precedent:

Forlano previews three realizations of her disabled cyborg perspective that are currently being made in collaboration with the visual artist Itziar Barrio. One translates the alert and alarm data from her smart insulin pump into movements that symoblize the years of sleep deprivation Forlano endured; another is a cement abstraction of an arm wrapped in what appears to be a blood pressure monitoring cuff. “The work is a reminder of the human labour that makes these automated systems work,” explains Forlano.

Soundbite:

“5:20 pm Sensor connected. 5:06 pm Sensor warm-up. 7:01 pm Calibrate now. 7:30 pm BG required. 7:31 pm Alert on low.”

Laura Forlano, sharing a stream of alert and alarm data transcriptions she transcribed from her smart insulin pump

Soundbite:

“AI, like all technological systems, is disabled. But our design processes are still overwhelmingly skewed towards optimization, perfection, efficiency, success, and a happy path. We vastly underestimate and minimize the ways in that they may fail, leaving others to suffer the consequences.”

Laura Forlano, on human hubris and technological delusions

Profile:

Louise Hickman

Louise Hickman is a research associate at the Minderoo Centre of Technology and Democracy, University of Cambridge. She holds a PhD in Communication from the University of California, San Diego, and her research draws on critical disability studies, feminist labour studies, and science and technology studies to examine the historical conditions of access work.

Soundbite:

“What value do we place on autobiographical encounters with technology? When I was two years old I started wearing a hearing aid. When I was sixteen I started using an electric wheelchair. More recently, in the last two months I’ve started using a white cane. I’ve named my white cane Gregory Bateson.”

Louise Hickman, introducing herself and her assistive technologies

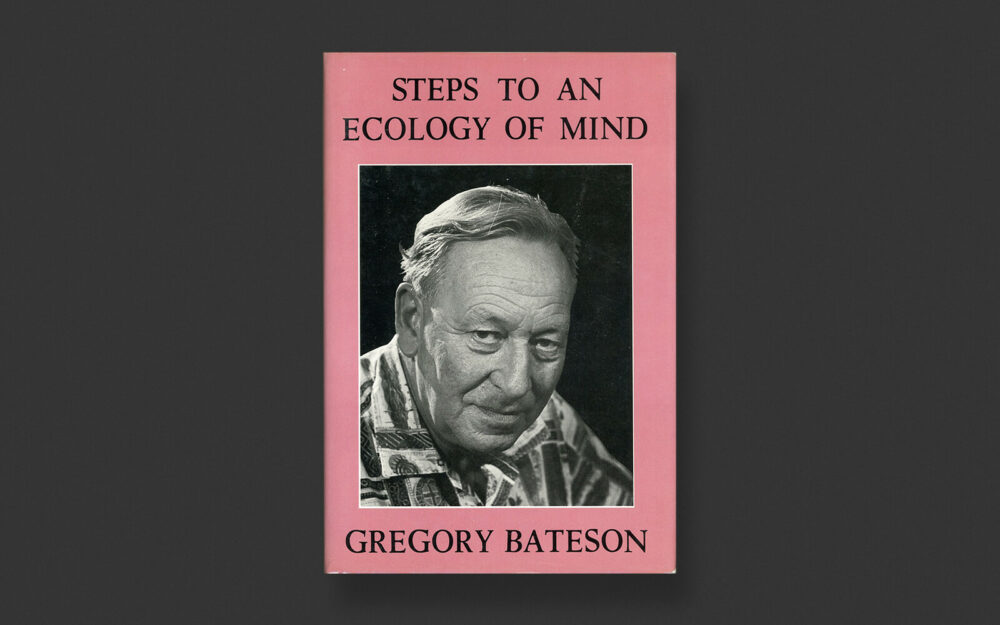

Precedent:

Hickman’s cane is named after British anthropologist and social scientist Gregory Bateson. The cited cane analogy is from Bateson‘s 1972 collection of essays Steps To An Ecology of Mind, where he writes [assistive technology] “is a pathway along which differences are transmitted under transformation, so that to draw a delimiting line across this pathway is to cut off a part of the systemic circuit which determines the blind person’s locomotion.”

Soundbite:

“Gregory Bateson asked his students one day: Where does the body start and where does the vision begin? Is it at the bottom of the cane? Is it halfway up? Is it at the tip? Or is it the path of travel? What he was asking his students to think about was the feedback loop and debunking the idea that the brain is the place of cognition.”

Louise Hickman, unfolding Gregory Bateson

Soundbite:

“How do stenographers build dictionaries? How do they code speech when it is happening in real-time? Everytime a stenographer produces a word it’s based on their own embodiment with their keyboard, laptop, and dictionary.”

Louise Hickman, situating (and explaining) stenography

Precedent:

In the LUX-commissioned short film Captioning on Captioning (2020), Hickman and the disabled artist Shannon Finnegan—an EYEBEAM resident at the time—meet with Hickman’s longtime collaborator and real-time writer Jennifer to reveal the machinations of access work. Over the course of four recorded Zoom sessions, the three discuss dictionary building, transcription errors, and speech-to-text latency, as Jennifer demos her use of the Case CATalyst stenography software. “By inverting the invisibility of real-time writing, we edited the film to show discrete moments of care, vulnerability, and intimacy,” Hickman writes on her website.

Soundbite:

“German sociologist Max Weber kept coming up as Darth Vader. Again and again my stenographer repeated the brief for Weber, but all that appeared on screen was Vader. Darth Vader, Darth Vader, Darth Vader.”

Louise Hickman, discussing “technological failure” with a personal anecdote: When her real-time writer Jennifer lost her laptop, she also lost the vocabulary she had been building with Hickman over two years.

Soundbite:

“Stenographers have ownership over their dictionaries—they’re not part of the datasets used for training AutoAI captioning services. In that sense, the politics of transcription become this local system the stenographer can be the gatekeeper of.”

Louise Hickman, on authorship and labour in an increasingly automated real-time economy

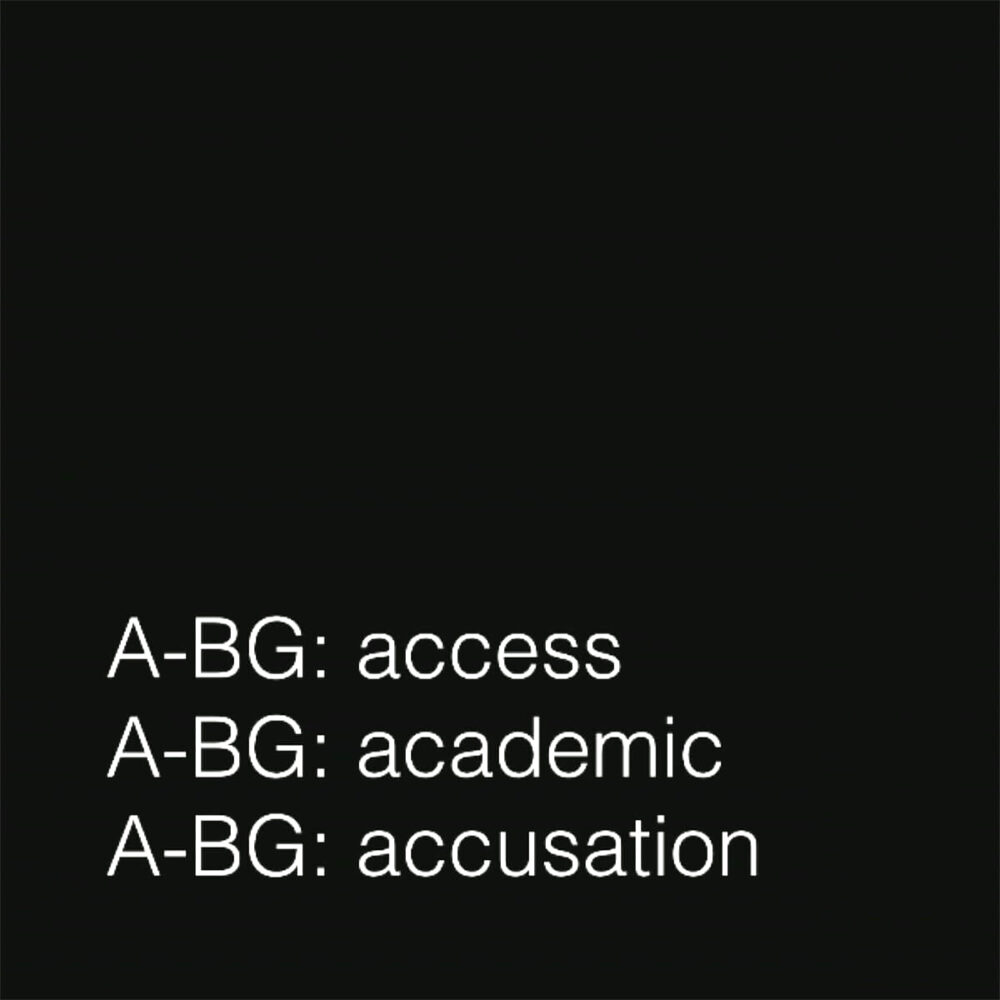

Precedent:

“There’s not one same dictionary for the entire cohort of stenographers,” explains Hickman. Underscoring the intimacy of a stenographer’s vocabulary, Hickman shares several steno briefs that, depending on dictionary, have widely different meanings: ‘A-BG,’ for example, can mean ‘access,’ ‘academic,’ or ‘accusation,‘ while ’PHA’ can mean ‘machine,’ ‘mental anguish,’ or ‘parole.’ “This is what I mean with stenographers having a relationship with their software,” notes Hickman.

Takeaway:

The word ‘universal’ often precedes the word access, but Hickman’s argument undermines the idea that some kind of totalizing access could ever be granted. Her nuanced discussion about the organic relationships that evolve between speakers and their stenographers—their mutual crafting of custom vocabularies—spells out a much more bespoke notion of access. Access is not some magic policy that levels the playing field, access provides time, space, and resources to support folks as they make their own way—on their terms.

Precedent:

Hickman harkens back to the bygone stenography devices and namechecks the Digitext-ST (Steno Translator) as a key benchmark. Invented in 1987 by Jerry Lefler, the clunky device was the first real-time shorthand machine for stenographers. “I’m a complete nerd, I want this in my house,” Hickman beams while telling the audience about its capabilities.

Soundbite:

“My thinking about the steno brief is really about captioning as a political economy. The choices that we make to interpret information and provide access. A deaf person in the Netherlands, for example, is entitled to 160 hours a year of access to a trained transcriptionist. That’s rationing of access, on a state level.”

Louise Hickman, on the politics of access

Process:

Midway through her talk, Hickman invites participants to stand up and inspect the captioning stations installed on either side of the stage. “This is about embodiment,” she reminds the audience, encouraging everyone to centre themselves around the screens. “I want you to check on everyone around you, and check about access—whether they can see, whether they have space.” As the audience follows, Hickman points out that host Autumn School has pathways to access built into it—and invisible labour that makes them run. Offstage, out of sight, speech-to-text translators Luisa and Christina labour to provide real-time captioning. “I’m naming them to recognize there are these other people in the room who are producing the access,” says Hickman.

Photography: Silke Briel

Photography: Silke Briel

Soundbite:

“Access work is intimacy work. As AI is exceedingly taking over access work—real-time captioning, for example—I’m interested in the distribution of that intimacy, how it becomes fragmented and contested.”

Louise Hickman, pondering intimacy when access work is automated