Making

Mirror

Stage

Nora N. Khan and HOLO ‘make a magazine in public’ via production notes, research snippets, and B-roll material.

Released in spring 2022, HOLO 3 features 16 luminaries exploring the profound implications of AI and computational culture.

© 2022 HOLO

Labyrinthine TXT “3” featuring words from Harold Cohen’s paper “What is an image?” (1975) is a generative type experiment by NaN.

Ten years ago, this very season, the first outlines of a yet to be named print magazine were being sketched—counter-intuitively so, as the first iPad had just been released and fast-paced digital publishing was all the rage. This new imprint would also be a misfit in other ways: neither art, design, science, nor a technology magazine, it was conceived as something in between—a magazine about disciplinary interstices and hybrid creative practices that are tricky to pin down. More interested in research, process, and entangled knowledge, it should not only explore but embody how niche developments influence other fields and, eventually, shape popular culture. Smart, methodical, and beautiful, the magazine should also have a lot of heart—and speak to many people.

Thousands of copies later, we’re still amazed at how HOLO resonated. It’s been described as “heavyweight in scope and literally” (Monocle), an “essential tool” (Jose Luis de Vincente) and an “extraordinary record” (Casey Reas), “that links discourse past, present, and future” (Nora O’Murchu). Over the years, HOLO visited the studios of interdisciplinary luminaries such as Ryoichi Kurokawa, Vera Molnar, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, and Katie Paterson; it featured analysis by erudite thinkers including James Bridle, Georgina Voss, and Geoff Manaugh; and experimental designers like Moniker, Coralie Gourgeochon, and Karsten Schmidt added touches that push what you can do in print (e.g. why wouldn’t you visualize every glyph on every page on intricate character distribution maps, or use reader-generated input to ‘grow’ cover art?). In short: the magazine had become a research vessel, encouraging all aboard to explore new territory through experimentation and collaboration. Thus far, we filled two hefty compendiums that each mark a point in time.

HOLO 3 will follow in that same tradition. But it will also break new ground—it has to. Similar to how the first issue filled a void in the blog and publishing sphere, the next one will have to speak to current needs. HOLO 2.5—this website—is an important step in that direction (read more about our online publishing intentions here). It’s the online home we long felt HOLO needed, and a framework that will help us situate and evolve the printed magazine.

Going forward, HOLO will be published annually, synthesizing a year’s worth of observations into a timely theme. Hence, the lion’s share of pages will be dedicated to the magazine’s research section—rigorous investigations that have always been at HOLO’s heart. Other sections will become more dynamic and move faster as we reimagine them on this site: Stream, the magazine’s year-in-review fold-out timeline, has already become a living archive; Encounters, our signature series of long-form interviews, will follow soon. This diversification of our editorial activities—sustained focus on the one hand, agility and nimbleness on the other—will allow us to bring you more content more frequently. Most importantly, it will make HOLO a better magazine.

HOLO 3 will be published in the summer of 2021. Until then, we’ll use this space to share production notes, research snippets, B-roll material, and select stuff from the bin—after all, a lot of work has been done already and some of it in vain. We hope you’ll follow along as we venture into uncharted territory—to explore both disciplinary interstices and HOLO’s new printed form.

HOLO 3 will become available as part of a new Reader account model to be launched in early 2021. If you previously ordered HOLO 3 together with HOLO 2, you will receive your copy automatically. For details on the new model—and how to become a HOLO Reader—see The Annual and our note on HOLO blog.

HOLO’s transformation begins with its core architecture—the ‘spaces’ that organize content into thematic and/or functional sections and provide the editorial framework of the magazine. They dictate not only how we navigate—and fill!—a publication; they set the pace for how things flow from page to page.

In HOLO 1 and 2, the architecture reflected what the magazine was designed to do: meet creative practitioners in their studios and explore emergent themes. Both issues (Model 1) feature two sizeable clusters of Encounters (A1, A2)—long-form interviews and studio visits—separated by a sprawling research section, Perspective (B), containing essays, surveys, and commentary. More complementary, Grid (C) set foot into nascent hybrid spaces—digital art galleries, creative incubators at scientific institutions—while Frames (D) examined emergent tools and tech. Stream (F) compiled news gathered during production and closed each issue by situating it in time.

With HOLO 3, we’re outgrowing that rigid formula. Years into navigating disciplinary interstices, we began to notice—and question—some of the hard lines we’d drawn in our magazine (e.g. why are artists and designers segregated from, for example, curators, researchers, and toolmakers?) Eager to build bridges within the magazine’s architecture, we became increasingly interested in aligning things with an overarching theme. Hence, a lot of work went into streamlining and consolidating—from tightening studio visits while expanding the space for inquiry (Model 2) to tying Grid and Frames closer to the research section (Model 3). The work on HOLO 2.5 was pivotal—as it came into focus, so has HOLO 3. The more we leverage this expanded online space for episodic interviews, profiles, and news, the further future print editions can lean into a single unifying theme (Model 4). Like a yearbook, “The Annual” will dig deep into a pressing topic, drawing on and responding to the stories we now share on HOLO.mg.

If anything, this production diary is a testament to just how much our thinking around print evolves with our online publishing. Take HOLO 3’s rejiggered framework, for example: in the previous entry, we argued that “the more we leverage this expanded online space for interviews, commentary, and news, the further future print editions can lean into a single unifying theme.” Energized by this new editorial architecture—see the aforementioned entry for fancy flow charts—we were eager to “dig deep into a pressing topic.” We hit a wall, instead: how can we pick a single theme with so many simultaneous urgencies? What’s the longevity of a timely research topic in light of mutating global crises and rapidly evolving tech? And, when examined within a thematic framework, wouldn’t AI, blockchains, the climate collapse (and a host of other forces shaping culture) yield a different periodical each year? That got us thinking.

What if, instead, we turned the annual publishing cycle into a research method, one that looks beyond a single topic and more at the state of things at large? Perhaps, this… Annual could bring together a wide range of luminaries to comment on ‘emerging trajectories’ across an expanse of entangled fields? Offering a yearly reality check, they could help us parse the present moment and better understand what lies ahead. We were intrigued!

But who’d get to be in this illustrious circle? In the past, we prided ourselves in carefully matching topics and contributors rather than soliciting ideas through open calls. It yielded the cohesiveness and journalistic flavour that, we’d argue, readers have come to appreciate about our magazine. But there’s something to be said about openness and making room for perspectives other than our own. Ten years into running HOLO in the same (fixed) configuration, it was high time for new and different voices to lead the way.

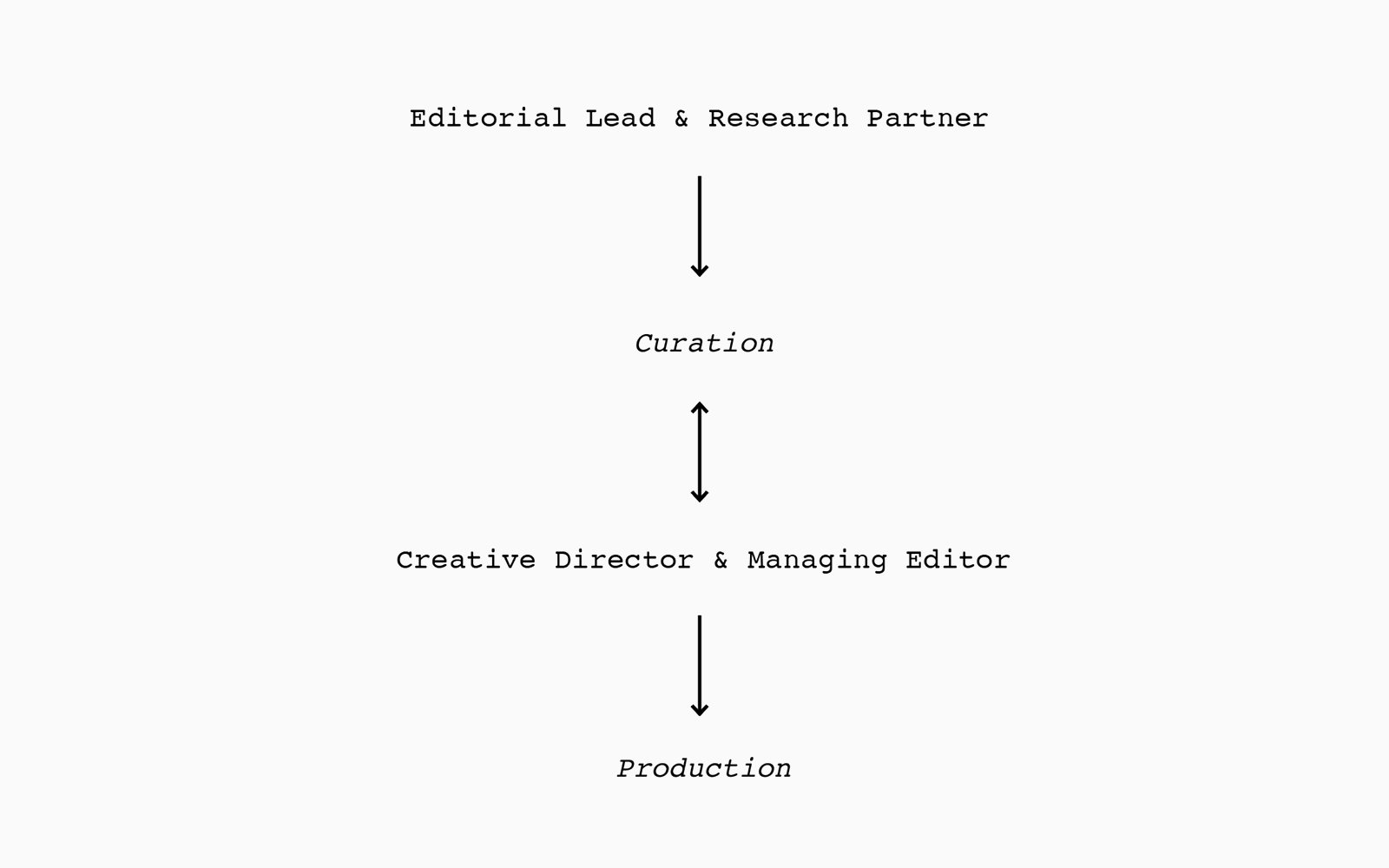

Going forward, each Annual will be spearheaded by a different Editorial Lead working alongside a Research Partner of their choice. Whereas the former will act as the chief tastemaker who finesses every page, the latter—an expert, a collective, an institution—will infuse niche knowledge and forge new connections along the way. Together, they set the Annual’s agenda, select contributors, and invent formats, all while sharing production updates here. We—Alex, Filip, and Greg—will remain hands-on, of course, and support production throughout the process.

Who will lead this year’s Annual? Over the holidays, we reached out to a few choice candidates, all trailblazers whose work we admire and who’d shine in this role. Their responses did not disappoint: after reviewing a stack of excellent proposals, we are thrilled to announce that an extraordinary talent has joined our team—and that we’ve entered production mode. We’ll name names in the coming days and are excited to hand over this production diary to our new collaborator soon.

Despite our expanding online efforts, HOLO’s print edition remains at the heart of what we do. Reimagined as a rotating research framework the HOLO Annual will explore disciplinary interstices with renewed focus and fresh voices in the mix. Every year, a guest Editorial Lead in close collaboration with a Research Partner will develop an agenda around pressing questions and invite a wide range of luminaries to respond. Today, we are proud to announce that Nora N. Khan will steer the 2021 HOLO Annual as Editorial Lead.

Nora N. Khan is a writer of criticism on digital visual culture and the philosophy of emerging technology. Her research focuses on experimental art and music practices that make arguments through software, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. She is a professor at Rhode Island School of Design, in the Digital + Media program, where she teaches critical theory and artistic research, writing and research for artists and designers, and the history of digital media. She’s also the curator behind “Manual Override,” the ambitious 2020 exhibition at NYC’s The Shed, that invited artists including Morehshin Allahyari and Martine Syms to “subvert the values of invasive technological systems.”

Nora first ‘blipped’ on our radar during her tenure with Rhizome, New York, where she shaped the internet and digital art imprint’s voice as editor and lead of its special projects arm. Over the years, we followed her thinking and commentary in top-tier art publications such as Artforum, Flash Art, Mousse, and 4Columns as well as several books. In Seeing, Naming, Knowing (2019), she parsed the logic of predictive algorithms and machine vision, and for Fear Indexing The X-Files (2017), she and co-author Steven Warwick binge-watched the entirety of the 90s sci-fi series and ruminated on its various phobias.

Right: In her most recent book, Seeing, Naming, Knowing (2019, The Brooklyn Rail), Nora parses the logic of predictive algorithms and machine vision

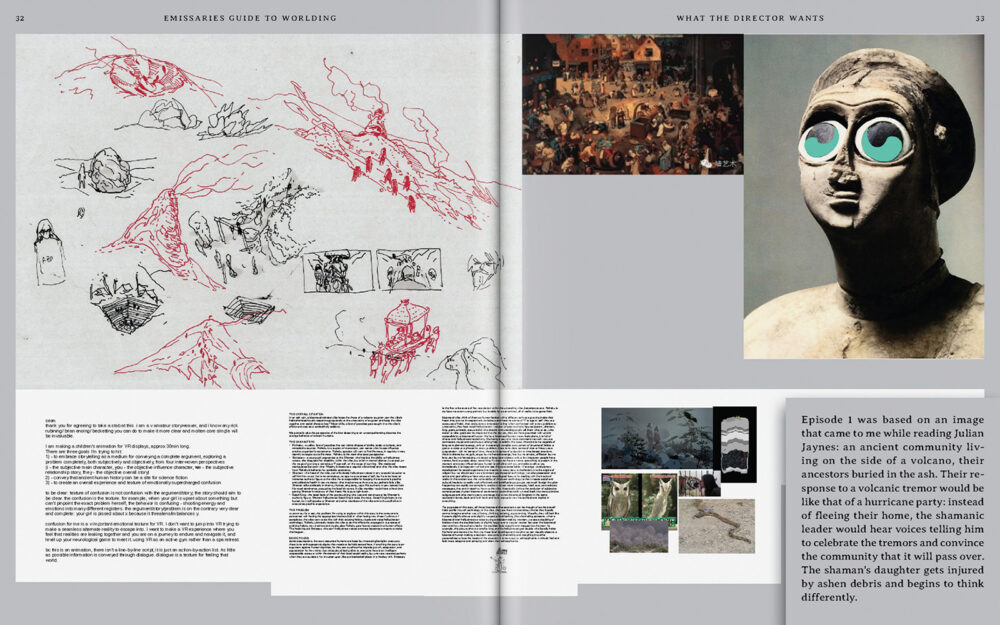

However, it’s her idiosyncratic collaborations with artists in the HOLO-verse that really captured our attention: she framed Casey Reas’ machine hallucinations in Making Pictures with Generative Adversarial Networks, worked alongside Sondra Perry, Caitlin Cherry, and American Artist on the installation A Wild Ass Beyond: ApocalypseRN, and meditated on Ian Cheng’s mythical simulations in Emissaries Guide to Worlding. And then there are weird and wonderful collusions that are a little harder to categorize: a virtual influencer that chronicled Unsound festival (with Team Rolfes), a libretto script for an opera about fiber-optic technology (with Bill Kouligas and Spiros Hadjidjanos), and fictions for an mixed reality installation about microbes (with Tuomas Laitinen). This transdisciplinary savviness in experimenting with narrative and format matches great with our ambitions for The Annual.

Nora joined our team in February, after outlining a bold vision in response to a private call we circulated amongst several of our favourite writers and editors. “How do we speak about technology as reflection of anxieties?” she asked in her proposal and argued: “Serious journalistic research ‘reveals’ the works of a system; artworks investigate the logic of machine learning; critics narrate the reveals.” It’s been non-stop brainstorming ever since. “I’ve drawn on my long, strange and winding travels through art editorial rooms, in and out of collaboration in art–technology spaces, to expand and hopefully deepen its scope,” she wrote in one of her emails. Similarly, under her leadership, The Annual will create (more) space for vital questions and expand the conversation.

We wholeheartedly welcome Nora to the HOLO team! In just a few short weeks her voice has enriched our thinking, offering fresh perspective, generous reflection, and incisive curiosity. We’re excited to support Nora realize her vision, knowing the HOLO Annual couldn’t be in better hands.

I am thrilled to join HOLO as the Editorial Lead for this year’s Annual. I’m Nora; I’m an editor, writer, critic, teacher, and curator. For ten years on, I’ve been editing and writing about the cultural impacts of technology, with a focus on developing what Sara Watson describes as “constructive technological criticism.” My hope has always been to expand the terms of what writing about and through technological and mediated culture can be. I’m particularly excited to join the thoughtful team at HOLO in producing the Annual to continue such work.

In working with, writing about, and teaching artists, technologists, and all in between, I keep returning to the importance of carefully weighing the language we use about technology. Right there—that “we”—is a bad tic that’s entered my own writing, influenced by years of reading technological criticism and essays that posit a “We” of our collective relationship to techne. As we are flooded cognitively by algorithmically-generated and human-generated discourse, I am especially interested in tracking, noting, the ways criticality is abraded by not just platforms, but also by the frameworks and terms of critique on offer. Even as critical analyses of the stakes of “new and emerging technologies” have become more common, sought out, and lauded as very necessary, there is ever the language of magic and enchantment entering alongside, almost hand in hand with developments in AI and machine learning.

Myths unfold in real-time alongside critical ‘reveals,’ unveilings, and clarifications. Binaries around understanding or misunderstanding proliferate. Cultural gaps between the humanities and the sciences expand even as artists and interdisciplinary practitioners work to collapse them. Many examples of extreme computational power increasingly claim space outside of, or beyond, language, critique, and historical understandings of power, sovereignty, and narrative. In this year’s Annual, we’ll engage with the new responsibilities that critics, theorists, programmers, technologists, and artists have to make sense of the mess, to cut through the confusion and obfuscation ever unfolding around computation. In the process, maybe we’ll even find ways to not say “the intersection of art and technology,” and revel instead in all the ways that technology has always drawn on artistic research, and artistic production has been technological or systematic.

The process of thinking through should take place in public, and is made more rich by being in public. Over the next few months, I hope to share the thinking and conversations around the development of the Annual as a print publication and archive, along with emerging experiments, works, and framings. I will talk through these tensions, between legibility and obfuscation, right here on the blog. We’ll talk about the debates and questions driving the issue, and how they’re being explored on the editorial and research side. I want you to be witness to the process of developing the frame and core themes for this year’s Annual, and to that end, I hope to be in conversation with you, and hear your thoughts. Please feel free to e-mail me here at nora@holo.mg about anything that sparks your interest in these posts.

Next up on the blog: an announcement of our Research Partner. The Research Partner is a vital part of the development of our theme: they are a sounding board and challenge. I will share reflections on my conversations with them, and further down the line, the invited artists, scholars, thinkers who will appear in the issue. Whether we will be talking through predictive methods and histories of algorithms, or broader cultural myths of the role of technology and creative practice, this blog will be a form of representing process in public, of making the collaborative process of producing a magazine—so often hidden in the back alleys, in shadows—fully legible. I’m delighted to share the process with you. Let’s begin.

In taking on the charge for this year’s Annual, I’ve tried to consider what it is one even might want to read in this year, of all years. What do we need to read, about computation, or AI ethics, or art, systems, emergence, experimentation, or technology? Where do we want to find ourselves, at any muddy intersections between fields, as we bridge so many ongoing, devastating crises?

I suspect I might not be alone in saying: it has been immensely, unspeakably difficult this year, to work, to write, and to think clearly and deeply about a single thing. To locate that kernel of interest that may have easily driven one’s writing, thinking, reviewing, in any other year. Such is the impact of grief, collective trauma, and loss: we put our energies into mental survival, not 10,000 word essays about ontology or facial recognition.

And yet many of us have persisted: giving talks, filing essays, publishing books, putting on shows while masked in outdoor venues, projecting work onto buildings, playing raves in empty bunkers, speaking on panels with people we’ll never meet. I have watched my favourite thinkers show up, to deliver moving performance lectures, activating their theory within and through this moment.

There was beauty, still. Watching poets and thinkers show up on screens to read from their work, addressing the moment, mirroring it, demanding more from it, in the middle of so much heartbreak. We watched Wendy Chun speak on “theory as a form of witness.” We watched Fred Moten and Stefano Harney challenge us to abandon the institution, abandon our little titles and little dreams of control. People we read, we continued to think with and alongside them. We tried to find ways to put their ideas into practice in our day to day.

This isn’t to valorize grinding despite crisis, but instead see the work as something done in response to and because of the crushing pressure of neoliberalism, technocracy, and surveillance, as all these forces wreak havoc in the collective. Maybe some of you have found something moving in this effort. I found it emboldening.

Right: Critical theorist and Black studies scholar Fred Moten, Professor at New York University and author of In the Break (2003), and other books.

Like most begrudging digital serfs, each day I also consumed way more content than I could ever handle. I followed the algorithm and was led by its offerings, trying to make sense of what is offered. As a critic tends to do, I also found myself tracking patterns. Patterns in arguments, patterns in semantic structures, patterns in phrases traded easily, without friction, between headlines and captions.

I found myself frustrated with the loops of rhetoric within the technological critiques I’ve made myself for a while now. In 2020, into 2021, there are ever more frantic discussions of black-boxed AI, “light” sonic warfare through LRADs used at protests, and iterative waves of surveillance flowing in the wake of contact tracing. Debates repeat: about human bias driving machine bias, about the imaginary of the clean dataset. Each day has a reveal of a new fresh horror of algorithmic sabotage. Artistic interventions, revealing the violence and inner workings of opaque infrastructure—seemed to end where they began.

It felt more important, this year, to connect our critiques of technology to capitalism, and to understand certain technologies as a direct extension—and expression—of the carceral state. I cracked open Wendy H.K. Chun’s Updating to Remain the Same (2016) and Simone Browne’s Dark Matters (2015) and Jackie Wang’s Carceral Capitalism (2018) again, and kept them open on my desk most of the year. When I read of both police violence and hiring choices alike offloaded onto predictive algorithms, I open Safiya Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression or Merve Emre’s The Personality Brokers. There were gifts—like Neta Bomani’s film Dark matter objects: Technologies of capture and things that can’t be held, with the citations we needed. I learned the most out of centering critical theory/pop sensation Mandy Harris Williams (@idealblackfemale on Instagram) on the feed.

I looked, in short, for the wry minds and voices in criticism, in media studies, in computational theory, in activism, and who also flow easily between these spaces and more, who have been thinking about these issues for a long time. A few had quieted down. Others had never really stopped tracking the patterns or decoding mystification in language. For years in the pages of HOLO, writers and artists have been investigating issues that have only built in intensity and spread: surveillance creep, digital mediation, networked infrastructure, and the necessary, ongoing debunking of technological neutrality.

We started this letter with noting patterns. Language patterns are the root of this Annual’s editorial frame. The language of obfuscation and mysticism, in which technological developments are framed as remote, or mystical, as partially-known, as just beyond the scope of human agency—crops up in criticism and discourse. One hears of a priestlike class in ownership of all information. Of systems that their creator-engineers barely understand. Of a present and near-technological future that is so inscrutable (and monumental) that we can only speak of the systems we build as like another being, with its own seeming growing consciousness. A kind of divinity, a kind of magic.

Right alongside this mythic language is also the language of legibility and technology’s explainability. A thing we make, and so, a thing we know. These languages are often side by side in the media(s) flooding us. Behind the curtain is the little man, the wizard, writing spells, in a new language. Legions of artists have worked critically with AI, working to enhance and diversify and complicate the Datasets. We’ve read about the diligent work of unpacking the black boxes of artificial intelligence, of politicians demanding an ethical review, to ‘make legible’ the internal processes at play. Is legibility enough? Legibility has its punishments, too. In 2020, Timnit Gebru, Google’s former Senior Research Scientist, asked for the company to be held accountable to its AI Ethics governance board. This resulted in Gebru’s widely publicized firing, and harassment across the internet. The horror Gebru experienced prompted critical speculation and derision about AI Ethics, a refinement in service of extraction and capitalism. It’s almost like … the problems are systemic, replicated, trackable, and mappable across decades and centuries.

As we are trawled within these wildly enmeshed algorithmic nets, how do we draw on these patterns, of mystification and predictive capture, to see the next ship approaching? To imagine alternatives, if escape is not an option? What stories and myths do we need to tell about technology now, to foretell models we need and can agree on wanting to live through and be interpreted by?

To start to answer this question, over the past month, we have asked contributors to respond to one of four prompts, themed Explainability and Its Discontents; Enchantment, Mystification, and Partial Ways of Knowing; Myths of Prediction Over Time; and Mapping and Drawing Outside of Language. They have been asked to think about models of explainability, diverse storytelling that translates the epistemology of AI, and myths about algorithmic knowledge, in order to half-know, three-quarters know, maybe, the systems being built, refined, optimized. They’ve been asked to consider speculative and blurry logic, predictive flattening, and the cultural stories we tell about technology, and art, and the space made by the two. Finally, to close the issue, a few have been asked to think about ways of knowing and thinking outside of language, in search of methods of mapping, pattern recognition, and artistic research that will help us in the future.

We can’t do this thinking and questioning alone. In the last weeks, we’ve gathered a first constellation of forceful responses—and the momentum is building. We are thrilled to begin to map these spaces of partial and more-than-partial knowing, and see what emerges, along with you all.

Each issue asks for the guest editor to choose a Research Partner, an interlocutor “who brings niche expertise and a unique perspective to the table.” I took this to mean a person who will be able to engage with the emerging frame, then provide feedback in a few sessions, as the magazine takes form. I first listed all my dream conversationalists, whose research and thinking I was drawn to. This list was long. It covered many possible expressions of research, from experimental and solitary to collaborative, hard scientific to qualitative and artistic research, computational to traditional archival research. There were literary researchers, Twitter theory-pundits, long-standing scholars in all the decades of experiments-in-art-and-technology, curators and editors who ground their arguments in original research.

As my editorial frame evolved into four distinct prompts, it seemed clear that the Partner would also need to confidently, easily critique the frame. They’d ideally provide prompts and encouragement from their perspective, expertise, practice, and scholarship,to help push the frame and broaden it.

I also realized that the HOLO Research Partner would have to pose a real challenge to my own thinking, and counter the clear positions and takes that come from being too far in (too far gone?) a dominant critical discourse about technological systems, which can often speak to itself (See: opening note). They’d sit outside of the inertia that can set in, as a field of inquiry and a mode of practice becomes known well, lauded, praised. (I think, here, of calls in which funders ask for guidance to “the most innovative work being done of all the innovative work being done in art and technology.”) As I wrote in my opening letter, this year has so swiftly turned us to embrace what we want to hear, take in, to what we still hunger to explore.

This is really when I thought of Peli Grietzer, a brilliant scholar, writer, theorist, and philosopher based in Berlin. Peli received a PhD from Harvard in Comparative Literature under the advisorship of Hebrew University mathematician Tomer Schlank. Peli’s work borrows mathematical ideas from machine learning theory to think through the ontology of “ambient” phenomena like moods, vibes, styles, cultural logics, and structures of feeling. Peli also contributes to the experimental literature collective Gauss PDF, and is working on a book project expanding on their “sometimes-technical” research, as they call it, entitled Big Mood: A Transcendental-Computational Essay on Art. He is also working on the artist Tzion Abraham Hazan’s first feature film.

I first ran across Peli’s writing and thinking through his epic erudition in “A Theory of Vibe”, published in 2017 in the research and theory journal Glass Bead. The chapters published were excerpted from their dissertation (which it sounds like they are currently turning into a book). I then virtually met Peli in 2017, over a shaky group call, in which a few Glass Bead editors and contributors to Site 1: The Artifactual Mind, called in from Paris and Berlin. Sitting in New York at Eyebeam on those old red metal chairs, I took frantic notes as Peli spoke. I struggled to keep up. It was exciting to be exposed to such a livewire mind. As it goes in these encounters, I felt my own thinking evolving, sensing, with relief, all the ways literary theory and criticism, and philosophical writing on AI could overlap in a way that many camps could start to speak to one another.

Most folks have noticed the distinctly generous qualities of Peli’s work, and have an experience reading “A Theory of Vibe,” too. The experience might begin with its opening salvos:

• An autoencoder is a neural network process tasked with learning from scratch, through a kind of trial and error, how to make facsimiles of worldly things. Let us call a hypothetical, exemplary autoencoder ‘Hal.’ We call the set of all the inputs we give Hal for reconstruction—let us say many, many image files of human faces, or many, many audio files of jungle sounds, or many, many scans of city maps—Hal’s ‘training set.’ Whenever Hal receives an input media file x, Hal’s feature function outputs a short list of short numbers, and Hal’s decoder function tries to recreate media file x based on the feature function’s ‘summary’ of x. Of course, since the variety of possible media files is much wider than the variety of possible short lists of short numbers, something must necessarily get lost in the translation from media file to feature values and back: many possible media files translate into the same short list of short numbers, and yet each short list of short numbers can only translate back into one media file. Trying to minimize the damage, though, induces Hal to learn—through trial and error—an effective schema or ‘mental vocabulary’ for its training set, exploiting rich holistic patterns in the data in its summary-and-reconstruction process. Hal’s ‘summaries’ become, in effect, cognitive mapping of its training set, a kind of gestalt fluency that ambiently models it like a niche or a lifeworld.

Through this playful use of Hal, readers are asked to consider and hold the “summaries” Hal makes, the lifeworld it models, to understand how an algorithm learns:

• What an autoencoder algorithm learns, instead of making perfect reconstructions, is a system of features that can generate approximate reconstruction of the objects of the training set. In fact, the difference between an object in the training set and its reconstruction—mathematically, the trained autoencoder’s reconstruction error on the object—demonstrates what we might think of, rather literally, as the excess of material reality over the gestalt-systemic logic of autoencoding. We will call the set of all possible inputs for which a given trained autoencoder S has zero reconstruction error, in this spirit, S’s ‘canon.’ The canon, then, is the set of all the objects that a given trained autoencoder—its imaginative powers bounded as they are to the span of just a handful of ‘respects of variation,’ the dimensions of the features vector—can imagine or conceive of whole, without approximation or simplification. Furthermore, if the autoencoder’s training was successful, the objects in the canon collectively exemplify an idealization or simplification of the objects of some worldly domain. Finally, and most strikingly, a trained autoencoder and its canon are effectively mathematically equivalent: not only are they roughly logically equivalent, it is also fast and easy to compute one from the other. In fact, merely autoencoding a small sample from the canon of a trained autoencoder S is enough to accurately replicate or model S.

From here, we climb the summit to Peli’s core claim:

• […] It is a fundamental property of any trained autoencoder’s canon that all the objects in the canon align with a limited generative vocabulary. The objects that make up the trained autoencoder’s actual worldly domain, by implication, roughly align or approximately align with that same limited generative vocabulary. These structural relations of alignment, I propose, are closely tied to certain concepts of aesthetic unity that commonly imply a unity of generative logic, as in both the intuitive and literary theoretic concepts of a ‘style’ or ‘vibe.’ […] One reason the mathematical-cognitive trope of autoencoding matters, I would argue, is that it describes the bare, first act of treating a collection of objects or phenomena as a set of states of a system rather than a bare collection of objects or phenomena—the minimal, ambient systematization that raises stuff to the level of things, raises things to the level of world, raises one-thing-after-another to the level of experience. […] What an autoencoding gives is something like the system’s basic system-hood, its primordial having-a-way-about-it. How it vibes.

It’s a heady journey, taking many re-reads to sink in. While I wouldn’t dare to try to capture Peli’s dissertation, “Ambient Meaning: Mood, Vibe, System,” I link it here instead for all to dive into, along with an illuminating interview with Brian Ng in which the two scholars debate core concepts in the work. Peli walks through the concept of autoencoders, and the ways optimizers train algorithms for projection and compression, and does so in an inviting, clear manner. This way, when we get to the real challenges of modeling and model training, we’re prepared.

Peli notes to Ng that they understand vibe as “a logically interdependent triplet comprising a worldview, a method of mimesis, and canon of privileged objects, corresponding to the encoder function, projection function, and input-space submanifold of a trained autoencoder.” They labor to create understanding of “a viewpoint where the ‘radically aesthetic’ — art as pure immanent form and artifice and so on — is also very, very epistemic,” noting, further, the ways folks like Aimé Césaire created “home-brew epistemologies […] where the radically aesthetic grounds a crucial form of worldly knowledge.” We eventually get to an exciting set of claims about the cognitive mapping involved in attending to, as Peli writes, the “loose ‘vibe’ of a real-life, worldly domain via its idealization as the ‘style’ or ‘vibe’ of an ambient literary work,” and that, further:

• Learning to sense a system, and learning to sense in relation to a system—learning to see a style, and learning to see in relation to a style—are, autoencoders or no autoencoders, more or less one and the same thing. If the above is right, and an ‘aesthetic unity’ of the kind associated with a ‘style’ or ‘vibe’ is immediately a sensible representation of a logic of difference or change, we can deduce the following rule of cognition: functional access to the data-analysis capacities of a trained autoencoder’s feature function follows, in the very long run, even from appropriate ‘style perception’ or ‘vibe perception’ alone.

I admire the ease with which Peli moves through genres and periods, weaving between literary theory and computational scholarship, helping us, in turn, move from the knottiest aspects of machine learning to the ways literary works might learn from analogies with computation. His scholarship is as generous as it is challenging. Throughout, we’re asked to consider common metaphors and analogies used in machine learning studies. The more traditionally literary-minded are challenged to consider proof of concept in a mathematical analogy, and what artificial neural networks—not particularly the most interesting models of thought—might promise literary theory and critical studies. As we move into realms where folks are frequently moving between cognitive theoretic models, discussions of artificial neural networks, and theory, and criticism, this is a powerful guide. We’re also asked to seriously consider how literary works move towards a ‘good autoencoding’ and in what traditions of aesthetic practice we might understand aesthetics as a kind of autoencoding. Peli creates a language through which we can move back and forth from cherished humanist concepts to the impulses of experimental literature, and to appreciate computational modeling as it helps us to map language out to its edges.

Back in April of 2020, I joined Peli for the third Feature Extraction assembly on Machine Learning, supported by UCLA, described as an exploration of the “politics and aesthetics of algorithms.” We had a fun couple of hours talking about the lifeworlds and strange logics of ML and predictive algorithms, with a group of artists and organizers at Navel in Los Angeles. I was struck, then, re-reading A Theory of Vibe three years later, how vital and alive its arguments, claims, its simultaneous experimentation and coherence, felt. In my many readings of this essay, I admired how Peli probed for unstated and unconsidered perspectives, pointed out blind spots, and how their questions were rooted in a set of exploratory hypotheses about the nature of art, and what computation allows us to see about the nature of art. They seemed a perfect interlocutor for this Annual.

As the Annual’s Research Partner, Peli has been remarkable and generous and good-humored. He is adept at the cold read, helps me make incisive cuts, always offers zoomed-out criticality. He’s helped us raise the stakes of the editorial frame, exposing us to writers and thinkers we’d not have met easily or fluidly otherwise, from computational linguists to researchers studying the computational mind to philosophers who speak through Socratic argument over our Zooms. It’s been thrilling to invite and get to know thinkers from his intense and rare circles.

Our main task, in working together, has been discussion of each prompt around prediction and fantasies of explainability and opacity, and the roles of language in mystification and mythologizing of technology as remote. As a result, the frame is more challenging, more provocative, pushing our respondents to think along broader timescale and social scales, and challenge themselves.

Over the next weeks in this Dossier, we’ll have a number of representations of our research conversations—a close-reading of Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI, along with snippets from our conversations about the Annual—together. They’ll be gestural excerpts of the deeper conversations underway. We’re sharing ideas and discussing them in tender forms with Peli. His openness, care for thought, and a genuine enthusiasm about unexplored concepts or lesser-theorized angles has only strengthened the possibilities of this issue. Thank you, Peli!

On a final note, a massive editorial project like this Annual requires intensive research and consideration of the wider intellectual and artistic field in which the artists, writers, and thinkers invited are working. I encourage editors to try and find someone who challenges their ideas and positions, and even questions the desire to go with the safer frame. Be in conversation with someone who pushes you intellectually, who will engage enthusiastically with the deeper philosophical and critical possibilities of writing and publishing. The Annual is better for this exchange and relationship—or, forgive me—this very vibe that Peli brings.

We’ve evolved to essentialize, to make representations of complexity, putting outsized pressure on the efficacy of those translators of meaning: metaphors, stories, carrier narratives.

In a very early conversation with Research Partner Peli Grietzer, we talked about the earliest, and blurriest, version of what this issue of the HOLO Annual could be. What did the ongoing debates around explainability and perfect legibility of black-boxed technologies—debates we’d often been enmeshed in—too often leave out?

Walking down a sunny street in Berlin, Peli relayed anecdotes of all the ways we know things halfway, and live with partial knowledge. This partial knowing is essential to our ways of navigating the world. We talked about animist spirits and gods. Peli mentioned spirits of rivers, part of a host of half-human and human-like beings which we’ve lived alongside for millennia. I think of bots and artificial intelligence, both “stupid,” in Hito Steyerl’s words, and a little- to much-less-stupid each day, as denizens of this realm of partial knowledge. We interact, speak, and form relationships with representations of people and things that we barely know.

Cognitively, we need to not know every single detail about complex phenomena unfolding around us. If we were to know and understand every computational decision being made on our laptop as it happens, we would barely be able to function. We’ve evolved to essentialize, to distill down, to make representations of complexity, putting outsized pressure on the efficacy of those translators of meaning: metaphors, stories, carrier narratives.

The political implications of thinking through these ways of knowing and not-knowing are far-reaching. Consider how the brutal realities of algorithmic supremacy are often contingent upon its mystification and its remove. We can map a growing hierarchy of computational classes of ‘knowers’ versus those without knowledge, those with more access to the workings of technology, those with partial access, and those with nearly none.

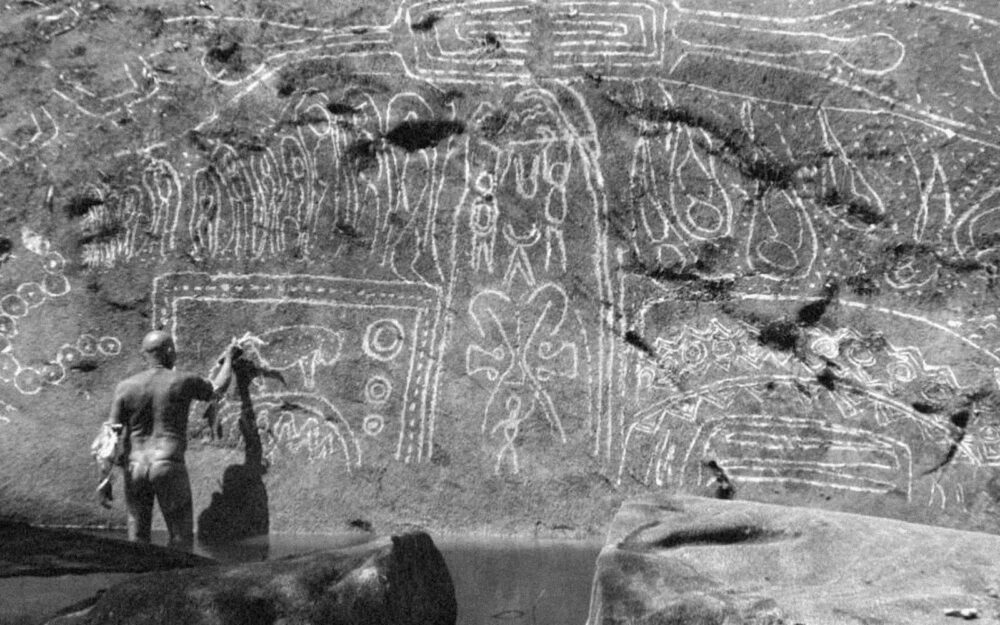

In sending out our first prompt, Enchantment, Mystification, and Ways of Partial Knowing, we hoped for our contributors to help us understand all the ways in which we don’t understand. Together, they have widened the frame to include ‘ways of partial knowing’ that have been exercised historically. What ways have we ‘half-known’ and ‘half-understood’ the appearance of new intelligence, human-like or not, throughout our evolutionary history? What ways of partial knowing do we exercise all the time? What knowledge processes are necessarily partial? In this frame shift, can we place speculative stories, myths about the growing body of artificial intelligence or algorithmic knowledge, in all its obfuscation and enchantment, in parallel to grand narratives of technology?

In responding to Enchantment, Mystification, and Ways of Partial Knowing, we asked the following authors and artists to pick up and pursue threads they’ve not had space for in their practice before. We also asked each to consider alternative styles, forms, and designs to express their ideas through.

Huw Lemmey is a novelist, artist, and critic living in Barcelona. He is the author of three novels: Unknown Language (Ignota Books, 2020), Red Tory: My Corbyn Chemsex Hell (Montez Press, 2019), and Chubz: The Demonization of my Working Ar6se (Montez Press, 2016). He writes on culture, sexuality, and cities for the Guardian, Frieze, Flash Art, Tribune, TANK, The Architectural Review, Art Monthly, Pin-Up Magazine, and L’Uomo Vogue, amongst others. He writes the weekly essay series utopian drivel and is the co-host of Bad Gays.

Elvia Wilk is a writer living in New York. Seven years ago, we began our time as contributing editors to Rhizome. We have been in loose communion over ideas over the years, often meeting at strange festivals and conferences in strange hotels. Elvia’s recent novel Oval, published in 2019 by Soft Skull Press, is in part a send-up of the artworld of Berlin. Her work has appeared in publications like The Atlantic, Frieze, Artforum, Bookforum, n+1, Granta, BOMB, and the Baffler, and she is a contributing editor at e-flux journal. Her book of essays called Death By Landscape will be published in 2022, also by Soft Skull.

Nicholas Whittaker is a doctoral student in the Philosophy department at the City University of New York Graduate Center. They work on understanding and propagating the conditions of possibility of black abolitionism as a world-ending enterprise. As they write, this work takes them through investigations into and celebrations of film, music, digital culture, language (and its limits), love, and black social and intellectual life. Their work (including forthcoming pieces) can be found in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, the Point, the Drift, Aesthetics for Birds, and the APA Blog.

Thomas Brett is an artist working in hybrid processes of film, animation and video games. Central to his practice is the transformative capacity of physical artefacts and their conversion to virtuality or myth. Through analogue construction and their digital capture, Thomas crafts worlds from these objects; producing hidden narratives of character and space reconfigured in tremulous ontology.

Nora N. Khan and Peli Grietzer on Models of Explanation, Explainability Towards What End, and What to Expect from Explainable AI

This year’s HOLO Annual has emerged in part through conversation between Nora Khan and Peli Grietzer, the Annual’s Research Partner. They discussed Nora’s first drafts of the “unframe” for the Annual (in resisting a frame, one still creates a frame) around prompts of Explainability, Myths of Prediction, Mapping Outside Language, and Ways of Partial Knowing, over months. Once drafts started rolling in, they discussed the ideas of contributors, the different angles each was taking to unpack the prompts, and the directions for suggested edits. They came together about four times to work on unknotting research and editorial knots. A deeper research conversation thread weaves in and out, in which Peli and Nora deconstruct the recent blockbuster Atlas of AI, by Kate Crawford.

The research conversation bubbles underneath the Annual, informing reading and finalizing of essays and commissions, and its effects finding a home in the unframe, all the edits, and the final works. The following excerpt is taken from the earlier stages of the research conversation, which began back in February and March of this year. Nora and Peli discussed the emerging frame of prompts before they were sent out to contributors. They walked through each to problematize the framing. A fuller representation of the research conversation will be published in the HOLO Annual.

Nora: Let’s talk about explainability. Explainable AI is one impetus for this prompt, and the issues involved in it. On one side, you hear this argument, frequently, in speaker circuits and keynotes, that once the black box of AI is open, all the naive, feeble-minded users of technology will somehow have a bit more agency, a bit more understanding, and a bit more confidence in relation to AI that is barely understood by its engineers. In my weaker moments, I’ve made the same argument. Another line of argument about explainability as a solution is grounded in the notion that once we understand an AI’s purpose, its reasoning, we’ll be blessed with an idealized model of reality, and receive, over time, a cleaned-up model of the world that’s been eradicated of bias.

Peli: Even before one gets to different humanistic or social ideals of explainability, there are already ambiguities or polysemies in terms of the more scientific conversation on explainability itself. One aspect of explainability is just: we don’t understand very well why neural network methods work as well as they do. There are a number of competing high level scientific narratives, but all are fairly blurry. None of them are emerging in a particularly solid way. Often you think, well, there’s many important papers on this key deep-learning technique … but find the actual argument given in the paper for why the method works ‘is now widely considered’ inaccurate or post hoc. So there’s an important sense of lack of explanation in AI that’s already at play even before we get to asking ‘can we explain the decisions of an AI like we explain the decisions of a person’—we don’t even know why our design and training methods are successful.

I would say stuff like, as an engineering practice, Deep Learning is poorly scientifically understood. It’s currently one of the least systematic engineering practices, and one of the ones that involve the most empirical trial and error, and guesswork. It’s closer to gardening, than to baking. Baking is probably more scientifically rigorous than deep learning. Deep learning is about the same as gardening, where there are a lot of principles that are useful but you can’t really very well predict what’s going to work, and what’s not going to work when you make a change. I probably don’t actually know enough about gardening to say this.

Anyway, that’s one sense in which there’s no explainability. One could argue that this sense of explainability pertains more to the methods that we use to produce the model, the training methods, the architectures, and less to the resulting AI itself.. But I think these things are connected in the sense in which, if you want to know why a trained neural network model tends to make certain kinds of decisions or predictions, that would often have something to do with the choice of architecture or training procedure. And so we’d often justify the AIs decisions or predictions by saying that they’re a result of a training procedure that’s empirically known to work really well. Then the question is, okay, but why is this the one that works really well? And then the answer is often, “Well, we don’t really know. We tried a bunch of different things for a bunch of years and the architecture and training procedures end up working really well. We have a bunch of theories about it from physics or from dynamical systems or from information theory, but it’s still a bit speculative and blurry.”

So there’s this general lack of scientific explanation of AI techniques. And then there are the senses that are more closely related to predictive models, specifically, and how one describes a predictive model or decision model in terms of all kinds of relevant counterfactuals that we associate with explanation or with understanding.

Nora: It seems this prompt can be tweaked a bit further to ask contributors, what are the stakes of this explainability argument, and what are some of its pitfalls? And further, what kinds of explainability, and explanation, do we even find valuable as human beings? What other models and methods of explainability do we have at play and should consider, and how do we sort through competing models for explainability? I figure this could help better understand the place of artists and writers now who are so often tasked, culturally, with the “storytelling” that is meant to translate and contextualize and communicate what it is that an AI produces, does, how it reasons, in ways that are legible to us.

In one of your earliest e-mails about the Annual, you mentioned how you are much more interested in finding paths to thinking about alternatives to the current order, rather than, say, investing in more critique of AI or demands for explainable AI to support the current (capitalistic, brutal, limiting, and extractive) economic order. It really pushed me to reconsider these prompts, and the ways cycles of discourse rarely step back to ask, but to what end are we doing all of this thinking? In service of who and what and why? I really want to offer contributors the option to critique this concept of explainability in technology, through this specific push in AI: what some have called the flat AI ethics space. When we ask, “What if we can just explain what’s inside of the black box?” we might also ask, to what end?

Making the “decision-making process” of a predator drone more “legible” to the general public seems a fatuous achievement. Even more so if it is an explanation in service of a capitalist state or state capital, and we know how that works.

Peli: Let’s take another example. Say, my loan application got rejected. I want to understand why I got rejected. I might want to know, well, what are the ways in which, if my application was different or if I was different, the result would be different. Or, I can want to ask in what ways, if the model was slightly different, would the decision be different. Or you can ask, take me, and take the actual or the possible successful candidate who is most similar to me, and describe to me the differences between us. It turns out the result is, there’s a variety of ways in which one could, I guess, formulate the kind of counterfactuals one wants to know about in order to feel or rightly feel it has a sense of why a particular decision took place.

Nora: If you were to ask the model of corporate hiring to explain itself, you would hope for a discourse or a dialogue. I say, “Okay, so you show me your blurry model of sorting people, and then I can talk to you about all of the embedded assumptions in that model, and ask, why were these assumptions made? Tell me all the questions and answers that you set up to roughly approximate the ‘summation’ or truth of a person, in trying to type them. And then I can respond to you, model, with all of the different dimensional ways we exist in the world, the ways of being that throw the model into question. What are the misreadings and assumptions here? What cultural and social ideas of human action and risk are they rooted in?” And once we talk, these should be worked back into the system. I really love this fantasy of this explainable model of AI as having a conversation partner who will take in your input, and say, “Oh, yes, my model is blurry. I need to actually iterate and refine, and think about what you’ve said.” It’s very funny.

Peli: Exactly. I think that’s the thing that one, possibly, ultimately hopes for. There might be a real point of irreconcilability between massive-scale information-processing and the kind of discursive reasoning process that’s really precious to humans. I feel like these are conflicts we already see even within philosophy. I feel like there’s a moment within analytic philosophy, where the more you try to incorporate probability and probabilistic decision making into rationality, the more rationality becomes really alien and different from Kantian or Aristotelian rationality that we intuitively—I’m not sure if that’s the right word—that we initially think about with reasoning. Sometimes I worry that there’s a conflict between ideals of discursive rationality and the kind of reasoning that’s involved in massively probabilistic thinking. It seems the things that we are intending to use AIs for, are essentially often massively probabilistic thinking. I do wonder about that: whether the conflict isn’t just between AI or sort of engineering, and this discursive rationality, but also a conflict between massively probabilistic, and predictive, thinking and discursive rationality. I don’t know. I think these are profoundly hard questions.

“Prediction has always been part of our cultural heritage, and societies find scientific ways to sort and distribute resources based on biased predictive thought.”

The first wave of HOLO contributors—Nicholas Whittaker, Thomas Brett, Elvia Wilk, and Huw Lemmey—swiftly gathered around the “ways of partial knowing.” As these pieces started to roll in, Peli Grietzer and I needed to light a new fire in another clime for more contributors to gather around. Maybe it is endemic to technological debates that we are drawn into intense binaristic divides. But I started to look across to the other side of the art-technological range, across from the ‘ways of partial knowing’ that seem to offer looseness, a space to breathe. Claims to full knowing, full ownership, or full seeing seem, rightly, harder to sustain these days. I’d written the partial knowing prompt in response to the suffocating grip of algorithmic prediction that I spend my days tracking and analyzing, to see how others articulate senses of the impossibility of perfect prediction, of human activity or thought.

But of course, there are many ways that prediction has always been part of our cultural heritage, and societies find scientific ways to sort, predict, and distribute resources based on biased predictive thought. I’ve a soft spot for critical discussion of predictive systems of control and the artists and theorists who analyze them. I’ve looked to thinkers like Simone Browne and Cathy O’Neill and Safiya Noble and artists like Zach Blas and American Artist, most frequently, for their insights on histories of predictive policing, predictive capture, and the deployment of surveillance in service of capture. I was particularly taken by 3x3x6, the Taiwan Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, created by Shu Lea Cheang, director, media and net art pioneer, and theorist Paul Preciado. (Francesco Tenaglia’s precise interview with both artists in Mousse is a must-read).

In the space, the Palazzo delle Prigioni, the two investigated the history of the building as a prison, and the exceptional prisoners whose racial or sexual or gender nonconformity led to incarceration: Foucault, the Marquis de Sade, Giaconomo Casanova, and a host of trans and queer thinkers throughout history. The work looks at historical regimes and political definitions of sexual and racial conformity, and the methods of tracking and delineating correct and moral bodies over time: the ways myths of prediction have unfolded in different ways throughout history.

I used these photos and this interview as inspiration this last pandemic year, which I largely spent struggling to complete an essay on internalizing the logic of capture for an issue of Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory (with an incredible list of contributions). In their introduction, Marisa Williamson and Kim Bobier, guest-editors, outline the theme Race, Vision, and Surveillance: “As Simone Browne has observed, performances of racializing surveillance ‘reify boundaries, borders, and bodies along racial lines.’ Taking cues from thinkers such as Browne and Donna Haraway, this special issue draws on feminist understandings of sight as a partial, situated, and embodied type of sense-making laden with ableist assumptions to explore how racial politics have structured practices of oversight. How have technologies of race and vision worked together to monitor modes of being-in-the-world? In what ways have bodies performed for and against such governance?”

The gathering of feminist investigations drew on surveillance studies and critical race theory to theorize responses to the violence of racializing surveillance. Between the theorists in this issue and the impact of 3x3x6, it seemed to me that surveillance-prediction regimes of the present moment must be understood as a repetition of every regime that has come before.

In a way, it turned out that the prompts of ‘partial knowing’ and ‘myths of prediction’ are more linked than opposed: Our ways of understanding others are already quite speculative and blurry; how is this blur coded and embedded, and what prediction methods that aim to clarify the blur, or make the blur more precise, are possible?

Even as we struggle to find ways to disentangle ourselves from predictive regimes and algorithmic nudging, we also need to tackle what prediction means, and has meant, for control, for statistics, for computation. This second prompt includes hazy, fuzzy, and over-determinant methods of prediction and discernment. The future, here, is one entirely shaped by algorithmic notions of how we’ll act, move, and react, based on what we do, say, and choose, now—a mediation of the future based on consumption, feeling, that is subject to change, that is passing.

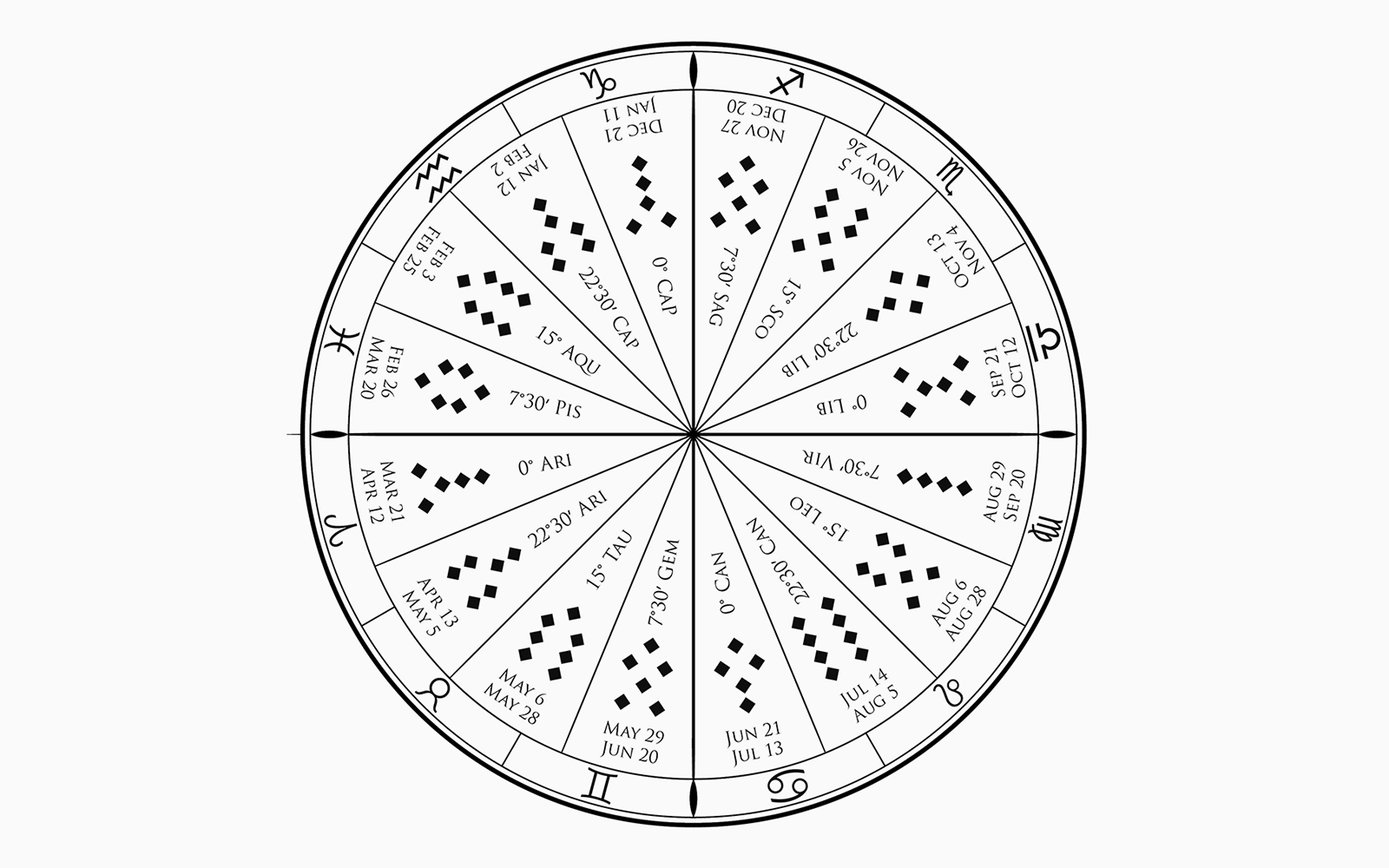

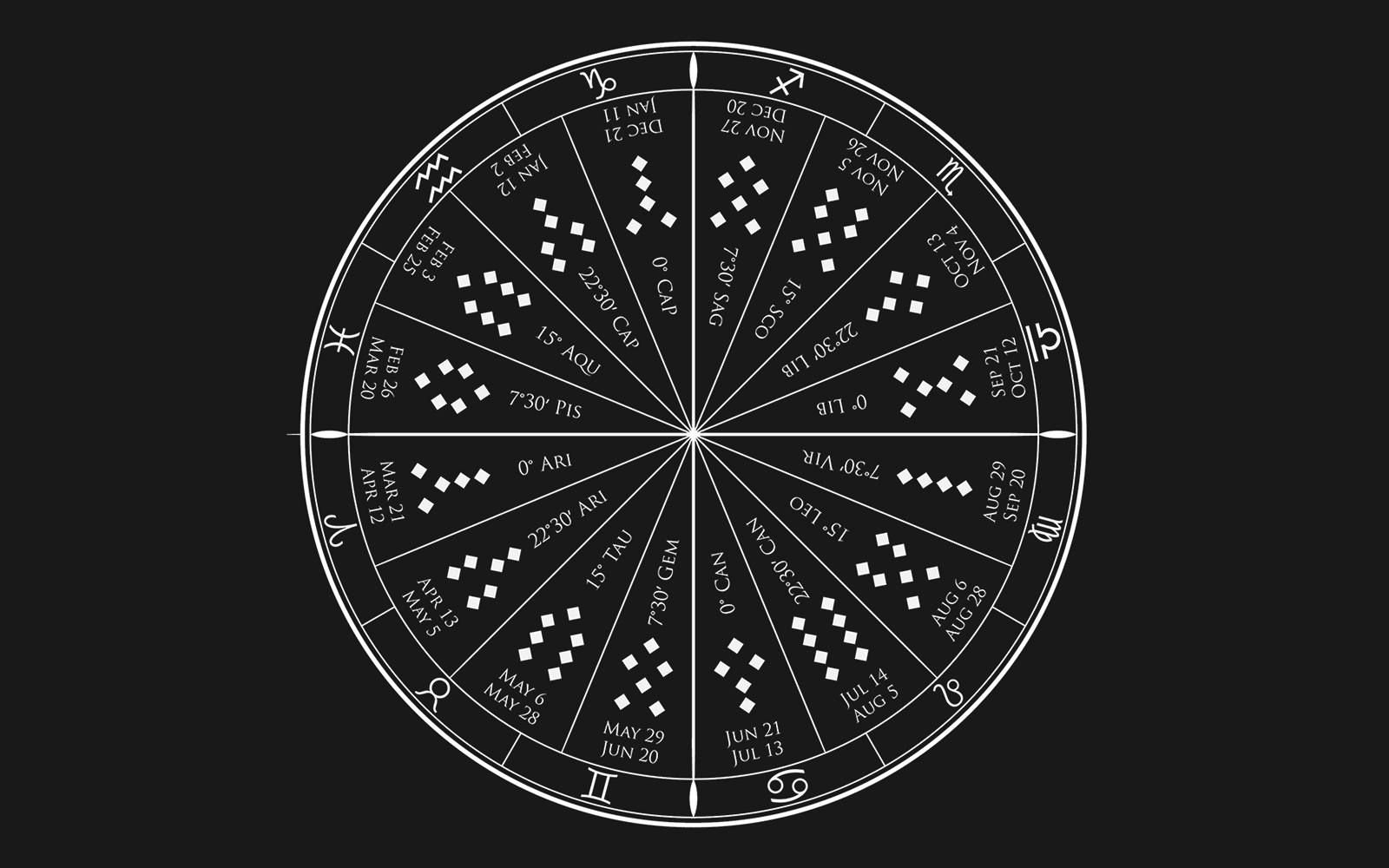

Four powerhouse thinkers—Leigh Alexander, Mimi Ọnụọha, Suzanne Treister, and Jackie Wang—join the Annual to respond to this prompt, Myths of Prediction Over Time. They were asked to think about the rise in magical thinking around prediction and the capacity of predictive technologies to become more intense as technological systems of prediction become more ruthless, stupid, flattening, and their logic, quite known. They look at the history of predictive ‘technologies’ (scrying and tarot and future-casting) as magic, as enchantment, as mystic logic, as it shapes the narratives we have around computational prediction in the present moment.

Together, they are invited to consider the algorithmic sorting of peoples based on deep historical and social bias; at surveillance and capture of fugitive communities; at prediction of a person’s capacity based on limited and contextless data as an ever political undertaking, or at prediction as they interpret it. They might reflect on the various methods for typing personalities, discerning character, and the creation of systems of control based on these partial predictions. They are further invited to look both at predictive systems embedded in justice systems, or in pseudoscientific tests like Myers-Briggs, for example, embedded in corporate personality tests.

Wang, Ọnụọha, Alexander, and Treister are particularly equipped to think on these systems, having consistently established entire spaces of speculation through their arguments.

Jackie Wang wrote the seminal book Carceral Capitalism (2018), a searing book on the racial, economic, political, legal, and technological dimensions of the U.S. carceral state. A chapter titled “This is a Story about Nerds and Cops” is widely circulated and found on syllabi. I met Jackie in 2013 as we were both living in Boston, where she was completing her dissertation at Harvard. She gave a reading in a black leather jacket at EMW Bookstore, a hub for Asian American and diasporic poets, writers, activists. I’ve followed her writing and thinking closely since. Wang is a beloved scholar, abolitionist, poet, multimedia artist, and Assistant Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. In addition to her scholarship, her creative work includes the poetry collection The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void (2021) and the forthcoming experimental essay collection Alien Daughters Walk Into the Sun.

Mimi Ọnụọha and I met at Eyebeam as research residents in 2016, and our desks were close to one another. One thing I learned about Mimi is that she is phenomenally busy and in high demand. She is an artist, an engineer, a scholar, and a professor. She created the concept and phrase “algorithmic violence.” At the time she was developing research around power dynamics within archives (you should look up her extended artwork, The Library of Missing Datasets, examining power mediated through what is left out of government or state archives).

Ọnụọha, who lives and works in Brooklyn, is a Nigerian-American artist creating work about a world made to fit the form of data. By foregrounding absence and removal, her multimedia practice uses print, code, installation and video to make sense of the power dynamics that result in disenfranchised communities’ different relationships to systems that are digital, cultural, historical, and ecological. Her recent work includes In Absentia, a series of prints that borrow language from research that black sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois conducted in the nineteenth century to address the difficulties he faced and the pitfalls he fell into, and A People’s Guide To AI, a comprehensive beginner’s guide to understanding AI and other data-driven systems, co-created with Diana Nucera.

If you’ve had any contact with videogames or the games industry in the last 15 years, Leigh Alexander needs no introduction. You’ve either played her work or read her stories or watched her Lo-Fi Let’s Plays on YouTube or read her withering and incisive criticism in one of many marquee venues. She is well-known as a speaker, as a writer and narrative designer focused on storytelling systems, digital society, and the future. Along with other women writing critically about games, including Jenn Frank and Lana Polansky, I’ve been reading and influenced by her fiction and criticism since 2008.

Alexander won the 2019 award for Best Writing in a Video Game from the esteemed Writers Guild of Great Britain for Reigns: Her Majesty, and her speculative fiction has been published in Slate and The Verge. Her work often draws her ten years as a journalist and critic on games and virtual worlds, and she frequently speaks on narrative design, procedural storytelling, online culture and arts in technology. She is currently designing games about relationships and working as a narrative design consultant for development teams.

Suzanne Treister, our final contributor to this chapter, has been a pioneer in the field of new media since the late 1980s, and works simultaneously across video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour. In 1988 she was making work about video games, in 1992 virtual reality, in 1993 imaginary software and in 1995 she made her first web project and invented a time travelling avatar, Rosalind Brodsky, the subject of an interactive CD-ROM. Often spanning several years, her projects comprise fantastic reinterpretations of given taxonomies and histories, engaging with eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research. Recent projects include The Escapist Black Hole Spacetime, Technoshamanic Systems, and Kabbalistic Futurism.

Treister’s work has been included in the 7th Athens Biennale, 16th Istanbul Biennial, 9th Liverpool Biennial, 10th Shanghai Biennale, 8th Montréal Biennale and 13th Biennale of Sydney. Recent solo and group exhibitions have taken place at Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, among others. Her 2019 multi-part Serpentine Gallery Digital Commission comprised an artist’s book and an AR work. She is the recipient of the 2018 Collide International Award, organised by CERN, Geneva, in collaboration with FACT UK. Treister lives and works in London and the French Pyrenees.

Stay tuned for more notes on the next two Annual prompts—on mapping outside language, and explainability—and the brilliant contributors on board. Also take note of the first in a series of research transcripts featuring conversation excerpts with our research partner Peli Grietzer about incoming drafts, the frame overall, and, well, all those atlases of AI.

Nora N. Khan and Peli Grietzer on Hazy Methods of Prediction, Tarot Compression, and Chomsky the Mystic

This year’s HOLO Annual has emerged in part through conversation between Nora Khan and Peli Grietzer, the Annual’s Research Partner. They discussed Nora’s first drafts of the “unframe” for the Annual (in resisting a frame, one still creates a frame) around prompts of Explainability, Myths of Prediction, Mapping Outside Language, and Ways of Partial Knowing, over months. Once drafts started rolling in, they discussed the ideas of contributors, the different angles each was taking to unpack the prompts, and the directions for suggested edits. They came together about four times to work on unknotting research and editorial knots. A deeper research conversation thread weaves in and out, in which Peli and Nora deconstruct the recent and influential Atlas of AI, by Kate Crawford.

The research conversation bubbles underneath the whole Annual, informing reading and finalizing of essays and commissions, and its effects finding a home in the unframe, all the edits, and the final works. The following excerpt is taken from the middle stages of the research conversation, which took place in July and August of this year. Nora and Peli discuss the drafts of essays which form the bulk of responses to the Annual Prompt “Ways of Partial Knowing,” and the ideas, debates, and dramas that the authors move through. A fuller representation of the research conversation will be published in the HOLO Annual.

Peli: There is a famous debate between Noam Chomsky and Peter Norvig, an AI guy from the generation between old fashioned AI and deep learning. The debate was about computational linguistics and sophistic linguistics. In an article from the early 2000s on the traits of Chomskyian linguistics, Peter Norvig quotes Chomsky in a derogatory way. He says something like, “Because Chomsky wants some kind of deep, profound understanding that goes beyond what statistics can provide for us, that’s because he’s some kind of mystic.”

You can find many papers, especially from two years ago, saying that deep learning isn’t science; it’s alchemy. The actual scientists tell each other all kinds of stories about, for example, why this method called layer normalization drastically improves results; there are a bunch of different theories about it. They’re either all kind of anecdotally phrased and not mathematically rigorous, or nobody really knows how they work, but there are all these different stories about how they do. One might describe this moment as a pre-scientific, proto-scientific, alchemical stage where we may have not particularly scientifically rigorous explanations, but instead, have complicated, intuitive stories about how the science works.

Nora: I love that. Describing the alchemic stage. I think these essays really capture those intuitive stories we use to understand or make sense of new technologies, or, methods and strategies humans create to approach the unknown. So far, the authors in this section get at partial ways of knowing very obliquely. They also talk about technology obliquely. At a slant and from the side. I love that for a magazine that is about science, art, technology, in explicit terms. I’m appreciative of how each lets the readers do a lot of the connective work, in the spaces between claims and ideas from each author. One author writes about dark speech on the rise, and delineates the different ways mystics and alchemists work with the limitations of language. The reader might ask, are alchemists on the rise in technological spaces? Is the difference between the mystic and alchemist, in relation to power and language, something that we can see in the present moment?

I’m really intrigued by this other piece on mapping GANs on top of tarot, and the idea of using one system to discern patterns in another predictive system. Could we go even deeper and ask, what do we learn about the way that tarot predicts or helps us figure out a place in the world? How does seeing a GAN’s interpretations of tarot images help us rethink and renew our understanding of what tarot does?

Peli: I think you’re super, super onto something here. And in fact, generative adversarial networks themselves are not predictive systems. They’re compression systems.

Nora: Right

Peli:Once you debunk the notion that tarot is “predicting the future,” well, what is it supposed to be? The cards represent different aspects of the human experience. The cards are models of a system, in which human experience is a system of 21 types of events, or 21 types of phenomena. Bring in the GAN, ask it, “Now, model this huge potential event database, resulting from the interaction between …” Actually, how big is the latent space of these GANs nowadays? I think the latent space uses something like 1,000 units. Both of them are archetype systems, because they’re summarizing a certain universal phenomena into archetypes.

Nora: So you have compression on top of compression. I think to your point, even though tarot doesn’t predict the future, what’s interesting is why we talk about them as though they do, even if we know that it’s pattern recognition and compression.

Peli: Yeah. I mean, I think we probably don’t have to be super literal about prediction as being prediction, about the future. I mean, we are actually talking about knowledge systems, right? I feel like prediction here is a bit of a synecdoche for knowledge and inferential systems in general.

Nora: Right, the notion that, based on a certain arrangement of cards on a certain day, there’s something about your character, described at that moment, on that day, before those cards, that is going to suggest what you’re going to be like next week, or a couple months or a year from now. You at least get a bit of steadiness about how to prepare: Here’s what you can expect.” I don’t know if that’s precisely prediction, in the way this essay partly about predictive and carceral policing is talking about, the carceral prediction our societies are embracing, or prediction within a carceral state. But instead, prediction here means a general, hazy, semi-confident narrative about what might happen, in the same way that you glean in an astrological reading.

Peli: Yeah. So, in machine learning: usually, when you turn a predictor, especially in modern machine learning, the predictor does implicit representation learning. GANs are just pure representation learning systems. You can then actually hook them up to a predictor, but usually hooking up predictors to representation learning systems of a different kind than GANs is more effective, for reasons we don’t fully understand.

Many people think that this is also a temporary thing, and one day, these kinds of generated models would be like representation learners for the purposes of then hooking up a predictor. But I think we don’t have to get super, super mired in stuff like defining things as being like prediction, or like other kinds of modeling.

Nora: Agreed! I think this way, prediction becomes a portal in this section, to think about all the hazy ways we have tried to predict, augur, and try to discern what’s coming—and to what end, and what we do with that belief.

We’ve stated it here before but it bears repeating: the most exciting part of reimagining HOLO 3 as the first of many HOLO Annuals was making room for other people’s ideas. It sounds cliché, but working closely with and handing control over to guest editor Nora N. Khan and her research partner Peli Grietzer helps us see this magazine and what it can be with fresh eyes. The same is true, of course, for the many new contributors, all interdisciplinary luminaries in their own right. Quite frankly, HOLO 3—the Annual—is a magazine that we, previously, couldn’t make. And that’s amazing!

But there’s also continuity. With so many new hands shaping the new edition, it felt right to bring back a few former collaborators without whom HOLO wouldn’t be the publication it is today. There’s trusted Andrew Wilmot, for example, a Canadian artist and author who expertly copyedited and proofread HOLO 1 and 2. We’re also thrilled to be working with the same Berlin-based art book printer, now called Druckhaus Sportflieger, that produced the previous editions. And where would we be without our distributor of many years: OML, part of the indie publishing hub Heftwerk, is gearing up to ship HOLO 3.

Yet, few collaborators have been more instrumental to HOLO’s distinction than Jan Spading and Oliver Griep of the Hamburg-based design studio zmyk. Over the years, they’ve laid out and obsessed over literally hundreds of HOLO pages and it is thanks to them, their experience, instincts, and diligence, that issue 1 and 2 made such a mark. So when HOLO 3—the Annual—came into vision, we had to invite them back. Over the past several months, the two accomplished art directors have been busy developing a new design language that speaks to and advances the Annual’s vision. With the print date nearing, we asked Jan and Oliver to share some insight into the design logic and development process (without giving too much away).

Regularly listed among Germany’s top design studios, the team of Jan Spading and Oliver Griep otherwise known as zmyk specializes in crafting cutting-edge books and magazines. Over the years, the two award-winning art directors have shaped signature publications such as DUMMY, fluter, and Frankfurter Rundschau and authored printed matter for clients such as Ostkreuz, brand eins Verlag, and Universal Music. Trivia: zmyk was founded in 2013, making HOLO one of the studio’s first imprints. (photo: Heinrich Holtgreve)

“That we ‘don’t exist outside of language’ seems a pretty core tenet of contemporary thought, and it is a seductive and powerful one to work from.”

Over the last two ‘Prompt’ entries (see here and here), we’ve introduced you to eight core contributors to this year’s HOLO Annual. Their precise insights and interpretations of each prompt dominated our summer, shaping the issue into a more layered and wild assemblage than we anticipated. With Research Partner Peli Grietzer, we’ve discussed creating a balance in tone and voice and style, a mix of poetic and didactic, hardline critiques and ekphrastic, joyous accounts. These are, after all, contributors we have met through their work first, whose inquiries shaped our own; they have each evolved many different and competing critical positions.

In commissioning for this Annual, I wanted to avoid having the final collective make any one strident position, or one set of insistent claims for. The essays, artworks, app- prototypes, maps of spaces outside maps, and alien languages you will encounter all take up disparate rhetorical, expressive strategies.

Taken together, the contributions flow from dreamspeak to radical cartography strategies, from straightforward polemics to critical memoir. It’s felt a bit like bringing friends from all your different parts of your life—internet, distant internet, gym, therapy, school, theory and writing, nightlife—to then see how they interact at a big strange party. This Annual is that free-for-all, each jostling up against each other from sometimes overlapping and sometimes competing positions.

In developing the third prompt—Mapping and Drawing Outside Language—I found I most needed to rescind the position I’m entrenched in as a critic—that of the capacity for language as the primary medium through which we understand the world. Writing and editing is where I spend much of my time, thinking on whether things can be described well or not, and how language shapes the world. That we “don’t exist outside of language” seems a pretty core tenet of contemporary thought, and it is a seductive and powerful one to work from.

Of course, this foundational notion—that language forms the substrate of thinking and generates the world alone—is easily complicated, and it needs to be. Many thinkers have argued that the dismissal of silence, or prayer, or any experiences before or beyond written and spoken language as ‘not real’ is a violent and statist form of thinking. Moreover, our lives are already largely determined by languages that activate beyond a common spoken language. Algorithmic language is largely unreadable for most people, unseen, and unspoken except by a select few; one could argue this is a space outside a commonly shared, legible written language. As Jackie and Mimi note in their pieces for the Annual, we live out the dictates of bureaucratic and computational decrees we can’t discern or necessarily read; in this sense, these are spaces outside of shared language.