← Explore

Prompt 3: On Mapping & Drawing Outside Language

“That we ‘don’t exist outside of language’ seems a pretty core tenet of contemporary thought, and it is a seductive and powerful one to work from.”

“That we ‘don’t exist outside of language’ seems a pretty core tenet of contemporary thought, and it is a seductive and powerful one to work from.”

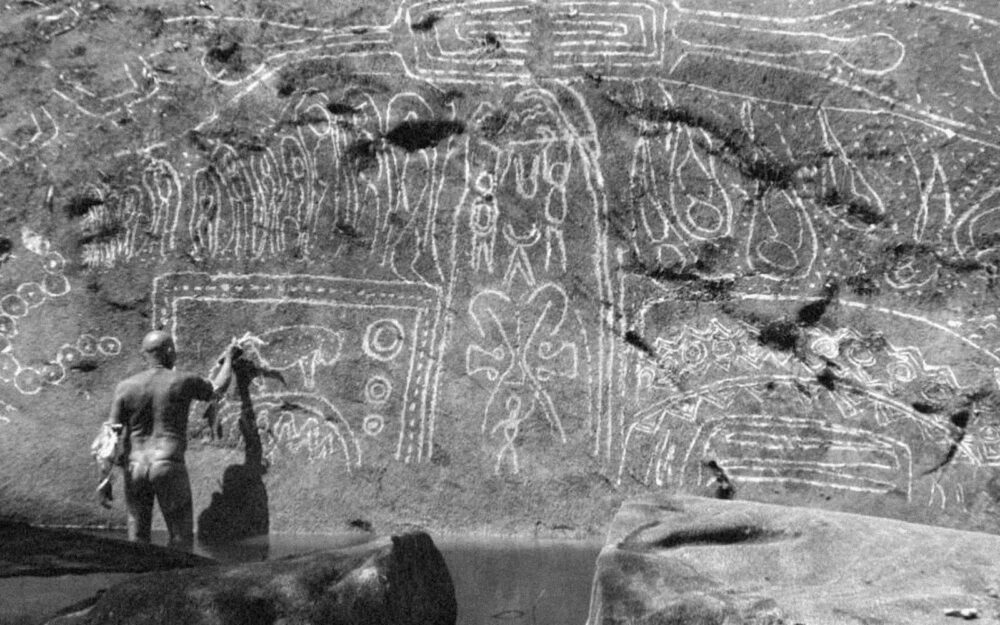

Scene from Embrace of the Serpent, a 2015 adventure drama film dedicated to lost Amazonian cultures directed by Ciro Guerra, and written by Guerra and Jacques Toulemonde Vidal

“I found I needed to rescind the position I’m entrenched in as a critic—that of the capacity for language as the primary medium through which we understand the world.”

Nora N. Khan is a New York-based writer and critic with bylines in Artforum, Flash Art, and Mousse. She steers the 2021 HOLO Annual as Editorial Lead

Over the last two ‘Prompt’ entries (see here and here), we’ve introduced you to eight core contributors to this year’s HOLO Annual. Their precise insights and interpretations of each prompt dominated our summer, shaping the issue into a more layered and wild assemblage than we anticipated. With Research Partner Peli Grietzer, we’ve discussed creating a balance in tone and voice and style, a mix of poetic and didactic, hardline critiques and ekphrastic, joyous accounts. These are, after all, contributors we have met through their work first, whose inquiries shaped our own; they have each evolved many different and competing critical positions.

In commissioning for this Annual, I wanted to avoid having the final collective make any one strident position, or one set of insistent claims for. The essays, artworks, app- prototypes, maps of spaces outside maps, and alien languages you will encounter all take up disparate rhetorical, expressive strategies.

Taken together, the contributions flow from dreamspeak to radical cartography strategies, from straightforward polemics to critical memoir. It’s felt a bit like bringing friends from all your different parts of your life—internet, distant internet, gym, therapy, school, theory and writing, nightlife—to then see how they interact at a big strange party. This Annual is that free-for-all, each jostling up against each other from sometimes overlapping and sometimes competing positions.

In developing the third prompt—Mapping and Drawing Outside Language—I found I most needed to rescind the position I’m entrenched in as a critic—that of the capacity for language as the primary medium through which we understand the world. Writing and editing is where I spend much of my time, thinking on whether things can be described well or not, and how language shapes the world. That we “don’t exist outside of language” seems a pretty core tenet of contemporary thought, and it is a seductive and powerful one to work from.

Of course, this foundational notion—that language forms the substrate of thinking and generates the world alone—is easily complicated, and it needs to be. Many thinkers have argued that the dismissal of silence, or prayer, or any experiences before or beyond written and spoken language as ‘not real’ is a violent and statist form of thinking. Moreover, our lives are already largely determined by languages that activate beyond a common spoken language. Algorithmic language is largely unreadable for most people, unseen, and unspoken except by a select few; one could argue this is a space outside a commonly shared, legible written language. As Jackie and Mimi note in their pieces for the Annual, we live out the dictates of bureaucratic and computational decrees we can’t discern or necessarily read; in this sense, these are spaces outside of shared language.

“This past summer, I watched Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent. I wept at the scale of loss of Indigenous knowledge, lost because it was unreadable.”

Still from Embrace of the Serpent, a 2015 adventure drama film dedicated to lost Amazonian cultures directed by Ciro Guerra, and written by Guerra and Jacques Toulemonde Vidal

“In 2017, there were an estimated 40 people left who could speak Ocaina, one of many endangered Amazon Indigenous languages.”

This past summer, I watched Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent with friends in San Miguel de Allende. I wept, in no small part because of the brutal depiction of the reality of the rubber holocaust in the Colombian Amazon, but also because of the film’s peripheral hints at the scale of loss of knowledge, lost because it was unreadable, or not in the language of the colonizer. The scale is shattering to try to wrap one’s mind around. The German and American ethnologist and ethnobotanist depicted in the film journey in pursuit of a hallucinogenic yakruna plant. Along the way, they gather Ocaina symbols, depict and mark down ‘the sense’ of rituals. Any Ocaina knowledge that can‘t be ‘put in the box’ or marked in the book in language, is not.

What goes in the travel journals and what is left out, never written down? In 2017, there were an estimated 40 people left who could speak Ocaina, one of many endangered Amazon Indigenous languages.

In Eduardo Kohn’s How Forests Think: Towards an Anthropology Beyond the Human (in which Kohn investigates how “a forest is alive and thinking, as is a dog, a jaguar, a peccary, and a plant,”) we find a central anecdote about jaguars early on. Kohn’s research was in Peru, where he is asked by the Runa (a Quechua speaker’s term for him or herself, referring to “people,”) to sleep with his face up so jaguars passing could recognize him, look at him looking back, and not attack. This is taken up as a moment of clear nonhuman communication, pre-linguistic or beyond language:

“Settling down to sleep under our hunting camp’s thatch lean-to in the foothills of Sumaco Volcano, Juanicu warned me, ‘Sleep faceup! If a jaguar comes he’ll see you can look back at him and he won’t bother you. If you sleep facedown he’ll think you’re aicha [prey; lit., ‘meat’ in Quichua] and he’ll attack.’ If, Juanicu was saying, a jaguar sees you as a being capable of looking back—a self like himself, a you—he’ll leave you alone. But if he should come to see you as prey—an it—you may well become dead meat.”

This is a complex anecdote. When the Runa asked Kohn to sleep face up, the notion implied is that the jaguars needed to see people, but as what? As other conscious beings? As beings worthy of living? Or beings that aren’t worth the risk of being attacked? We place our linguistic and value frameworks on the jaguar. Further, Kohn needed to go to sleep trusting this knowledge, that the jaguar sees the sign of human eyes looking back and then has a way of understanding, or— intuiting?—or perceiving, the sign of his open eyes. I wish to better understand, here, how the jaguar really understands, perceives and sees a world of implied signs, and how nonhuman life forms process signs. In other words, I want words for what there are not yet, quite, words for.

“If we want to understand how the magic of intelligence can be encoded in numbers, we should give up asking where. To attempt to locate consciousness in a network of interlinked signals, whether simulated or real, is to search for a mind within a mind.”

The third prompt of the HOLO Annual is “Mapping and Drawing Outside Language,” and gathered in response are Francis Tseng, Nick Larson, and K Allado-McDowell. In a conversation with research partner Peli Grietzer, we hoped for invited contributors to respond to a prompt around mapping and ways of understanding that are not necessarily based in language.

In shaping this prompt, Peli had introduced us to a piece of writing by Alex Graves of DeepMind, titled “Magic Numbers.” In it, Graves asks, how might we locate “the locus of creative magic within the billions of numbers processed by artificial neural networks?” How can “simple mathematics … cast the same spells as the grey stuff in our skulls?” What forms of mapping and drawing outside language do you deploy? They go on to write:

• If we want to understand how the magic of intelligence can be encoded in numbers, we should give up asking where. To attempt to locate consciousness in a network of interlinked signals, whether simulated or real, is to fall into the homunculus fallacy, the search for a mind within a mind. Instead we should embrace the quality of quantity, the necessity for life of patterns too intricate to put into words, and patterns of patterns, and so on up. The reductive drift of Western thought has tended to leave the celebration of complexity to artists and poets: Hopkins’ “pied beauty” or Whitman’s “I contain multitudes.”

While we were initially thinking of computational drawing and mapping practices that capture the complexity of the mind, Tseng, McDowell, and Larson all came to mind. They’ve worked through this notion through their respective practices, based in social justice and equity-driven modeling, AI aesthetics and research, and subtle investigations of the relationship between interfaces, image compression and degradation, and ideology, respectively. Get to know this heady group more formally below:

K Allado McDowell

Writer, speaker, musician, and author of Pharmako-AI (with GPT-3) and The Atlas of Anomalous AI (with Ben Vickers)

Writer, speaker, musician, and author of Pharmako-AI (with GPT-3) and The Atlas of Anomalous AI (with Ben Vickers)

Francis Tseng is a software engineer and lead independent researcher at the Jain Family Institute, where he presently works on topics such as Brazilian municipal social wealth modeling and Half-Earth game design. His seasonal interests include agriculture/food, repair, thermal comfort, and simulation. In the past he was a co-publisher of The New Inquiry, where he contributed to projects such as White Collar Crime Risk Zones and Bail Bloc. He’s usually happy to help with projects that lay the ground for a better world (whatever that means), so don’t hesitate to reach out.

Nick Larson is an artist and designer currently based in Providence, Rhode Island. His work investigates moments of noise, static, and ambiguity in the world around him. His practice involves image processing, compression, degradation, and multimedia composition. For inspiration, he loiters in ambiguous moments in search of hyperbole and melodrama. He is currently researching the aesthetics of online misinformation, conspiracy, and extremist ideologies.

K Allado-McDowell is a writer, speaker, and musician. They are the author, with GPT-3, of the book Pharmako-AI, and are co-editor, with Ben Vickers, of The Atlas of Anomalous AI. They record and release music under the name Qenric. Allado-McDowell established the Artists and Machine Intelligence program at Google AI. They are a conference speaker, educator and consultant to think-tanks and institutions seeking to align their work with deeper traditions of human understanding.

In our next post, we’ll introduce the final prompt, around Explainability, which in many ways was the start and remains the core of the HOLO Annual. Stay tuned!