← Explore

Keynote

The Artificial and the Synthetic: Intelligence, Language, Model

Speakers:

Benjamin Bratton

Orit Halpern

Profile:

Benjamin Bratton

Benjamin Bratton is Professor of visual arts at UCSD in San Diego, and author of The Stack (2016) and The Revenge of the Real (2021), which, respectively, schematize systems of scale and governance after Big Tech, and consider what politics in a post-pandemic world could be. Bratton is also the Program Director for The Terraforming, an initiative at Moscow’s Strelka Institute that tasks design students with tackling the radical transformations required for Earth to remain a viable host for life.

Soundbite:

“A thought experiment: what if the iconic blue marble photograph was a blue marble movie. One that showed the entire multi-billion year history of humankind in fast forward? You’d see volcanoes erupt, life form, and after that blur, in the very last few moments of that movie you’d see the wrapping of the sky in satellites, the formation of an intricate planetary crust capable of sensing—the emergence of planetary sapience.”

Benjamin Bratton, hijacking the discourse around the ‘blue marble’ photograph and using it to tell a different story about humanity’s history and place in the galaxy

Takeaway:

Bratton opens by locating the history of technology as also being a history of thought. Noting the true product created by philosophers of technology (like the recently passed Jean-Luc Nancy) is that grappling with the implication of new technologies reveals new facets of how we already think, and how we might think in the future.

Takeaway:

Recent AI systems move beyond the clumsiness of early chatbots like ELIZA. Their ability to understand and respond to semantics and engage in wordplay—actions we’d normally associate with intelligence—suggest we’ve crossed a threshold where artificial systems can absorb knowledge. We’ve been stuck in a loop for a while with our discourse about these systems though: we erroneously confuse their competency for comprehension.

Soundbite:

“It didn’t feel like a factory in the Charlie Chaplin Sense: it felt like a garden in the Richard Brautigan sense.”

Benjamin Bratton, on the euphoric sense of synergy and synchronization he felt when visiting an intensely automated factory in Shenzhen

Definition:

The ‘Artificial’ in artificial intelligence is located in the artifact, in material culture. Example: an arrowhead reveals an intentionality towards the natural world.

Fave:

“We’re using our distributed computer power to distribute 4K video on TikTok when we could be dedicating those resources to sophisticated natural language processing.”

Precedent:

Hatched between 1964–66 at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory by Joseph Weizenbaum, ELIZA is a mock psychotherapist—and the original chatbot. Based on early natural language processing, the program used pattern matching and substitution to create the appearance that it was responding to user text input. This attempt to simulate human speech patterns, and, more cunningly, basic empathy (ELIZA might ask “How do you feel about cars?” after a user mentioned them) could fool someone for a moment, but it only takes a few interactions to realize “it’s not smart, it just spits back responses that humans associate with intentionality. There’s really nobody home.” While crude, ELIZA succeeded as a proof of concept demonstration of Alan Turing’s evocative Turing Test hypothesis.

Soundbite:

“Creating synthetic intelligence is less about our creating machines that think how we think we think, but that we encounter machines that think differently and reflect the larger scope of what thinking actually is.”

Benjamin Bratton, clarifying his position on productive goals for machine intelligence

Profile:

Orit Halpern

Orit Halpern is an associate professor at Concordia University in Montréal, working within the Speculative Life cluster within the Milieux Institute. Her work bridges histories of science, computing, and cybernetics, and she is the author of Beautiful Data (2015).

Soundbite:

“There’s an emerging territoriality that’s coming out of procurement centres and data infrastructures.”

Orit Halpern, on how space has been permeated by software

Model:

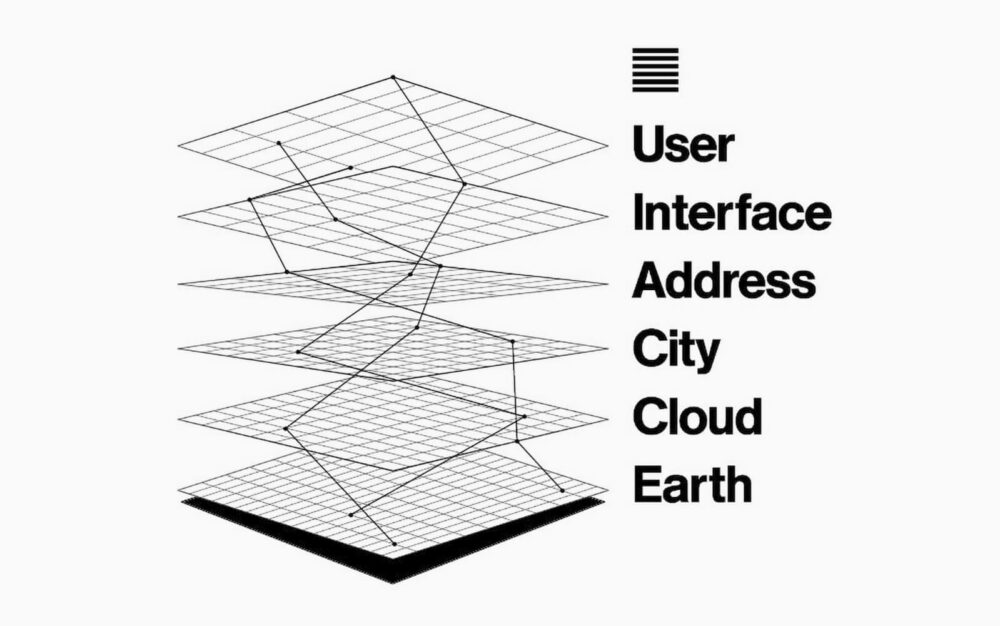

The metaphor at the heart of Benjamin Bratton’s 2016 book The Stack is exactly that: a layer cake of ‘levels’ that animate the world. Bratton describes this assemblage as an “accidental megastructure” and the interaction of earth, cloud, city, address, interface, and user are the points of inflection for global governance. Appropriating the rhetoric of ‘a tech stack’ of libraries and protocols, or even vertical integration, the stack is a diagram that replaces the Mercator map of yesteryear—its neat and tidy delineations between states—with a new messy reality of corporatized Big Tech shaping geopolitics and lived experience.

Stack diagram by Metahaven.

Stack diagram by Metahaven.

Soundbite:

“The 1990s mythology that computation was virtual and immaterial got us into a lot of trouble.”

Benjamin Bratton, linking digital immateriality with the climate crises

Takeaway:

‘Data’ and ’waste’ are problematic qualifiers for thinking about what gets generated by technological systems. The distinctions are not as clear-cut as we might think are and often what we label as one, might actually be the other.

Takeaway:

We’ve been overly “blunt” in how we use the word ‘surveillance,’ and focused on its negative connotations. A more useful term is ‘sensing layer’ whereby that monitoring is mobilized for governance. In the popular vernacular about surveillance there is a concern about individuals being seen, watched, and compromised, but there are just as many cases of communities and bodies not being seen or tended to (e.g. the many demographics that have become invisible during the pandemic). We’ve been collecting the wrong data—habits of consumption—and it does not help conceive or implement needed positive social change. Climate science is a key example of the kind of datasets and archives we should be building—and acting on.

Soundbite:

“No one single neuro-anatomical disposition has a privileged monopoly on how to think intelligently. What might qualify as intelligence is not duty-bound to any species or phylum. The ability of an organism, however primitive, to map its own surroundings, particularly in relation to the basic terms of friend, food, and foe, is a primordial abstraction, which we do not graduate from so much as develop from this to something like reason and its local human variations.”

Benjamin Bratton, dismissing the primacy of human consciousness

Resources:

• Benjamin Bratton, “Planetary Sapience,” Noema (2021)

• Richard Brautigan, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” (1969)

• Anastasia Sinitsyna et al, “Face As Infrastructure” (2020)

• Richard Brautigan, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” (1969)

• Anastasia Sinitsyna et al, “Face As Infrastructure” (2020)

Commentary: