← Explore

On View: Hommage à Barbaud (1974)

“First, the number of concentric squares in each set is randomly altered, disrupting the optical vibration of the grid.”

“First, the number of concentric squares in each set is randomly altered, disrupting the optical vibration of the grid.”

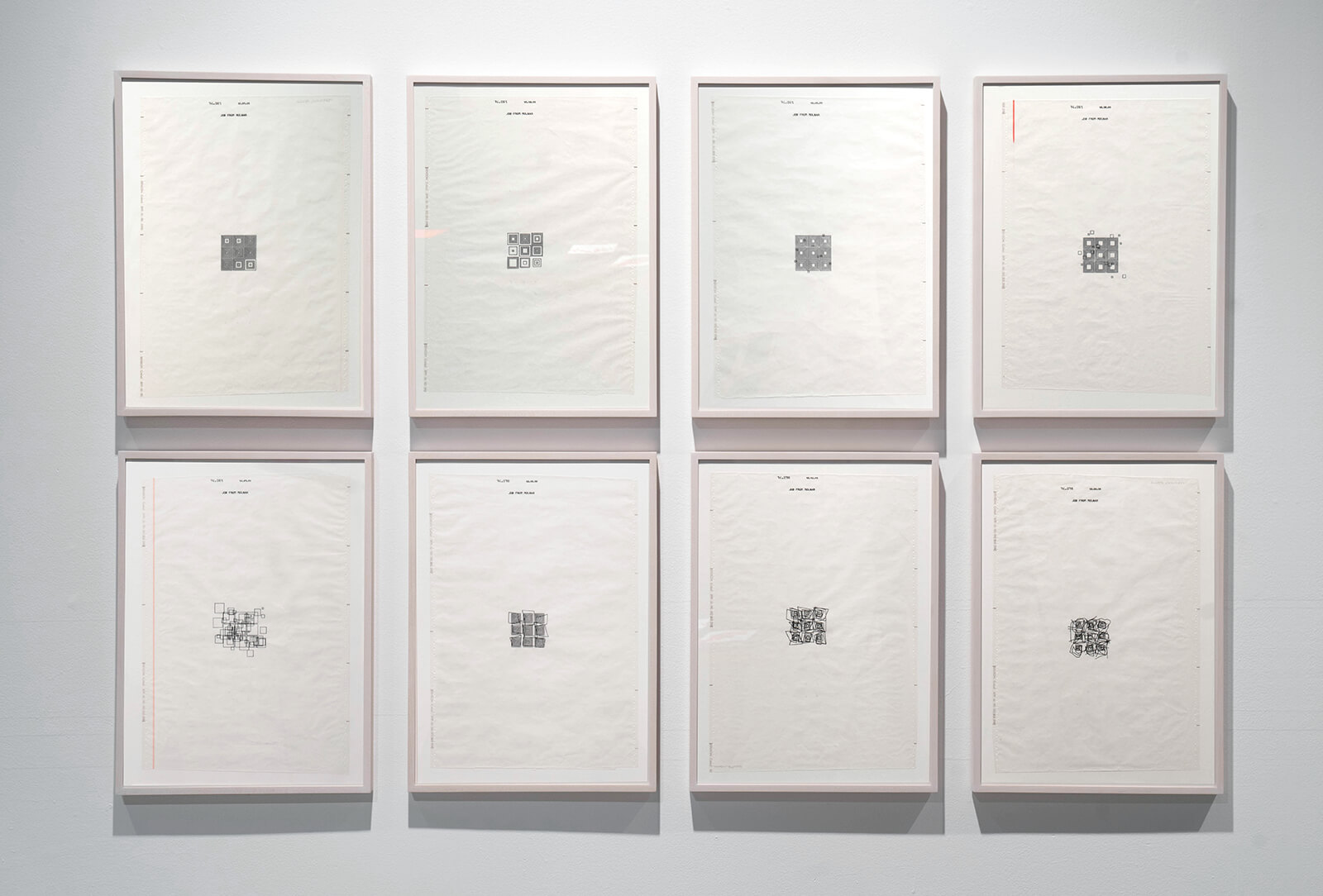

Vera Molnar, Hommage à Barbaud 1-8 (1974), Benson plotter drawing on paper, 20 x 14 in. / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection

“Then, the concentric squares snap back to the grid, but their central square is randomly displaced, like a fish hanging on to a sea anemone.”

It’s a theme that recurs in many of Vera Molnar’s works, as recognizable as her signature: concentric squares that bend in and out of shape until they become a tangled net of squiggles, no longer recognizable as neat geometric forms. This is the basis of Hommage à Barbaud, the first work from “Variations” that we’ll explore in this dossier. Molnar made this series of eight plotter drawings in 1974, one of her most prolific years.

A matrix of nine sets of seven concentric squares transforms according to three different patterns: first, the number of concentric squares in each set is randomly altered, disrupting the optical vibration of the grid. Then, the concentric squares snap back to the grid, but their central square is randomly displaced, like a fish hanging on to a sea anemone. The rest of the squares follow this pattern until they are completely dislodged from their grid. The grid then resets again, this time transforming by way of the sides of the square being replaced with other geometric forms—curves, diagonal lines. By the final transformation, we have a mess of squiggles, in which we must strain to find the underlying structure.

Molnar’s oeuvre is full of homages to other artists, from Dürer to Monet to Mondrian. But who was Barbaud? Pierre Barbaud (1911–1990) was one of the founders of algorithmic music in France, and a close friend of Molnar and her husband, François. By dedicating a work to Barbaud, Molnar immortalizes the impact of algorithmic music on her work, and on early computer art more broadly.

Pierre Barbaud with one of Molnar’s plotter drawings from the series À la recherche de Paul Klee (1970-71), exhibited in “Ordinateur et création artistique” at L’Espace Cardin, Paris, in October 1973 (archives of Vera Molnar, used with artist’s permission)

Though Molnar was friends with other visual artists in Paris, some of them her former art school classmates from Budapest—Simon Hantaï, Judit Reigl, Marta Pán—it was with experimental composers—Pierre Barbaud, Michel Philippot, Janine Charbonnier, Jean-Claude Risset—that she really clicked with. They shared an interest in working with parameters and chance procedures, but in a more systematic way than Dadaist automatism or the neo-Dada of the 1950s. It was from Philippot that Molnar borrowed the term machine imaginaire, her systematic approach to making pictures from around 1958 to 1968. Using basic concepts from combinatorial mathematics and analog ‘randomness generators’ like a roll of dice, Molnar ‘generated’ series of drawings by altering one parameter at a time. Each variation was executed painstakingly by hand.

“By dedicating a work to Barbaud, Molnar immortalizes the impact of algorithmic music on her work, and on early computer art more broadly.”

It was thanks to Barbaud that Molnar accessed her first machine réelle, an actual electronic computer. Barbaud had spent the last decade experimenting at Bull–General Electric in Paris, composing music with their mainframe computer free of charge in exchange for promoting and consulting for the company. Barbaud and Molnar ran in the same circles and, according to Molnar, on the same wavelength, too. They both participated in the 1965 SIGMA festival of contemporary art in Bordeaux, where Barbaud’s Musica d’invenzione was performed alongside pieces by Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis. In 1968, he invited Molnar to Bull take “his” mainframe for a spin.

Soon after, Molnar began experimenting at the Sorbonne university computing center in Orsay, just southwest of Paris. She worked there unofficially—clandestinely, she would say—mostly on evenings and weekends. Here, Molnar used an IBM system/370 mainframe computer and a drum plotter manufactured by the French company Benson, a name visible in the margins of most of her 1970s works, just outside the sprocket holes used to feed rolls of paper through the machine. At the top of each page is a timestamp and the words “JOB FROM MOLNAR,” referring to the computer program “Molnart” that she and her husband co-wrote in Fortran.

“So now all of them are going out of place,” Vera Molnar explains the progression from Hommage à Barbaud plot 2 to 3 in her Hungarian mother tongue. “They’re still squares, which is important, still exact squares, but their center is no longer there. It’s scattered.” On May 1, 2022, during her latest research trip to Molnar’s retirement home in Paris, Zsofi Valyi-Nagy asked the generative art pioneer to elaborate on the 1974 series of plotter drawings that is now on view at the Beall Center for Art + Technology. A video recording of their conversation (including English subtitles) is available here.

For collectors and enthusiasts, these marginal details have become all but marginal. But until quite recently, Molnar did not consider them part of the work. In the earliest days, she would carefully cut out her computer graphics, gluing the thin, almost transparent plotter paper to a thicker support. When she started selling her work in the 1990s, she was advised to cover the margins with a passe-partout, so that the image could pass as handmade. Now, Molnar has joked to me, “JOB FROM MOLNAR” is what gives the work market value. “You can forge my signature, but you can’t forge that,” she laughs.

This marginal text allows us to reconstruct the order in which Molnar programmed these images, to develop some understanding of her working process and of the algorithms she used—of which very little documentation remains. In fact, the sequence in which Molnar shows her series—whether in exhibitions or artist’s books—rarely corresponds to the chronological order in which she made them. Barbaud was made over the course of two days, Wednesday, September 18 and Saturday, October 5, 1974. Molnar worked on other series simultaneously, including Out of Square and Love-Story, which also explored twisting and tangling her favorite geometric shape.

Vera Molnar, Hommage à Barbaud (1974), Benson plotter drawing on paper, 20 x 14 in. / installation view: The Beall Center

for Art + Technology, Irvine, California (US) / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection / photo: ofstudio

“The progression from order to disorder in Molnar’s series is artificially constructed. We only see a small selection of outputs from dozens of variations; even their sequence is based on subjective choice.”

Why does it matter that Molnar doesn’t show Barbaud in the order it was made? It may not seem significant, but ultimately the progression from order to disorder in Molnar’s series is artificially constructed. Not only do we only see a small selection of outputs from dozens of variations, but even their sequence is based on subjective choices made by the artist.

It’s a bit ironic, then, that this work is named for Barbaud, because he couldn’t have had a more different approach to algorithms. As Jean-Claude Risset writes, Barbaud refused to “arrange” the results of his compositional programs.1 Molnar also recalls this fundamental difference between their approaches: while Barbaud believed all of his randomly generated results were of equal aesthetic value, Molnar would compare and contrast results until she found the ones she wanted. It was always her—not the program—who had the last word.

This is an age-old question in generative art that remains relevant today. In a recent conversation2 between Casey Reas and Harm van der Dorpel at DAM Projects in Berlin, these artists debated the difference between messing with a program and messing with its results, changing the algorithm or changing the outputs. For some, tinkering is “cheating”—Barbaud certainly would have thought so. But for Molnar, tinkering is possibly the most important creative gesture in her practice. This is something I will continue to explore in the coming weeks.

“While Barbaud believed all of his randomly generated results were of equal aesthetic value, Molnar would compare and contrast results. It was always her—not the program—who had the last word.”

References:

(1) Risset, Jean-Claude. ‘Une Experimentation Plastique En Actes’. In Véra Molnar: Une Rétrospective, 1942-2012, edited by Sylvain Amic, 28–35. Paris: Bernard Chauveau, 2012.

(2) Casey Reas and Harm van der Dorpel. “A conversation on art, software and NFTs,” DAM Projects, Berlin. April 22, 2022 / a recording of the conversation is available online here