← Explore

On View: Inclinaisons (1971)

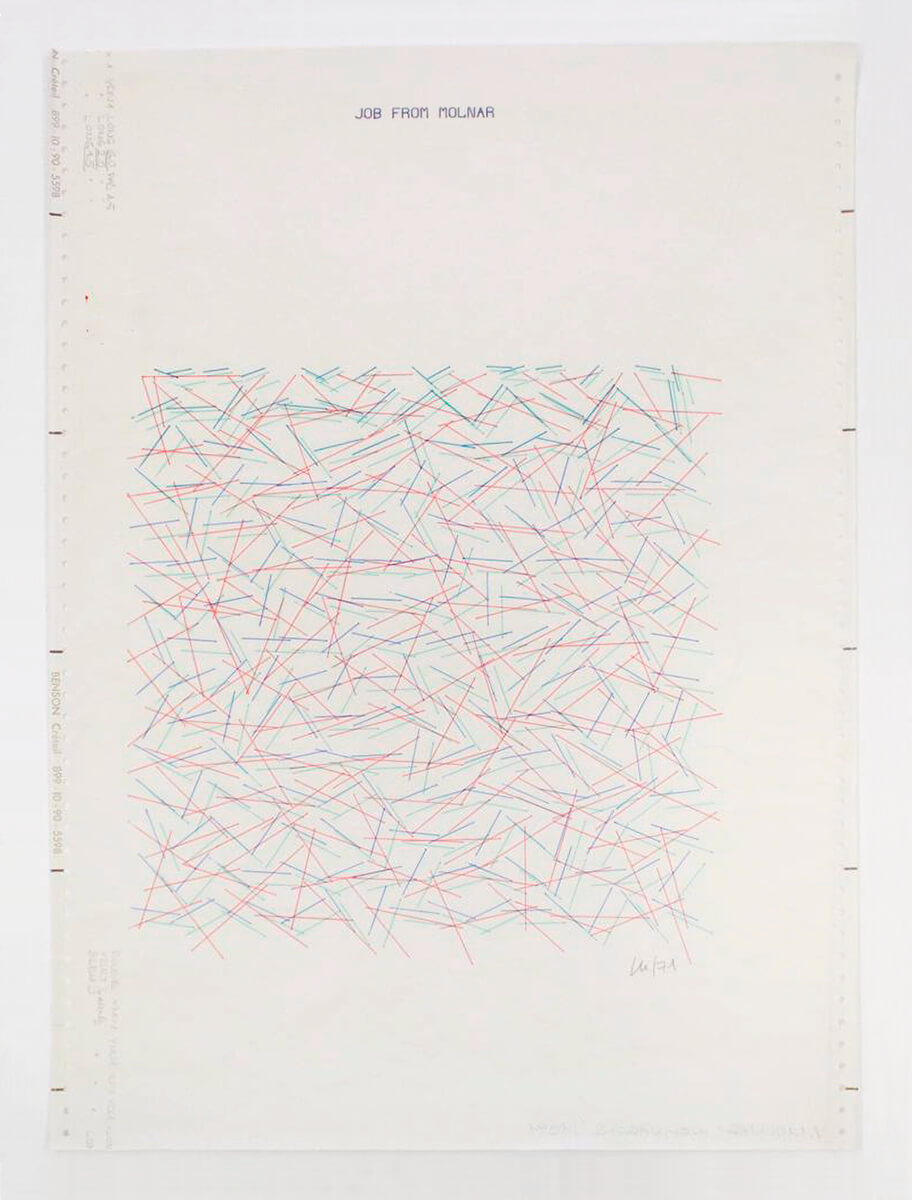

“In this plotter drawing, we see line segments in red, green, and blue—the three additive primary colours—scattered over a square surface area like a game of pick-up sticks.”

“In this plotter drawing, we see line segments in red, green, and blue—the three additive primary colours—scattered over a square surface area like a game of pick-up sticks.”

Vera Molnar, Inclinaison (Inclination), 1971, Coloured plotter drawing on Benson paper,

19.75 x 14 in. (unframed) / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection

“Inclinaisons, like its English cognate inclination, refers to a tilt, a line that runs oblique to the horizontal plane.”

Vera Molnar loves colour as much as the next painter, but we rarely see colour in her plotter drawings from the 1970s. Much like the juice and blood she experimented with, the marks of coloured plotter pens were more ephemeral — highly light sensitive and not designed to last. In this plotter drawing Inclinaisons from 1971, however, we see line segments in red, green, and blue — the three additive primary colours — scattered over a square surface area like a game of pick-up sticks.

Inclinaisons, like its English cognate inclination, refers to a tilt, a line that runs oblique to the horizontal plane. The word might be used to describe the lines in a graph that a scientist would output to paper using the same tools as Molnar. But Molnar’s ‘figure’ seems to mock the orderliness of scientific data. Her lines lead to nowhere, point to nothing. Their random distribution produces a visual rhythm, given more texture by the colour variations. At points, the colours overlap, creating teals, purples, and browns that anchor the eye, if only for a moment.

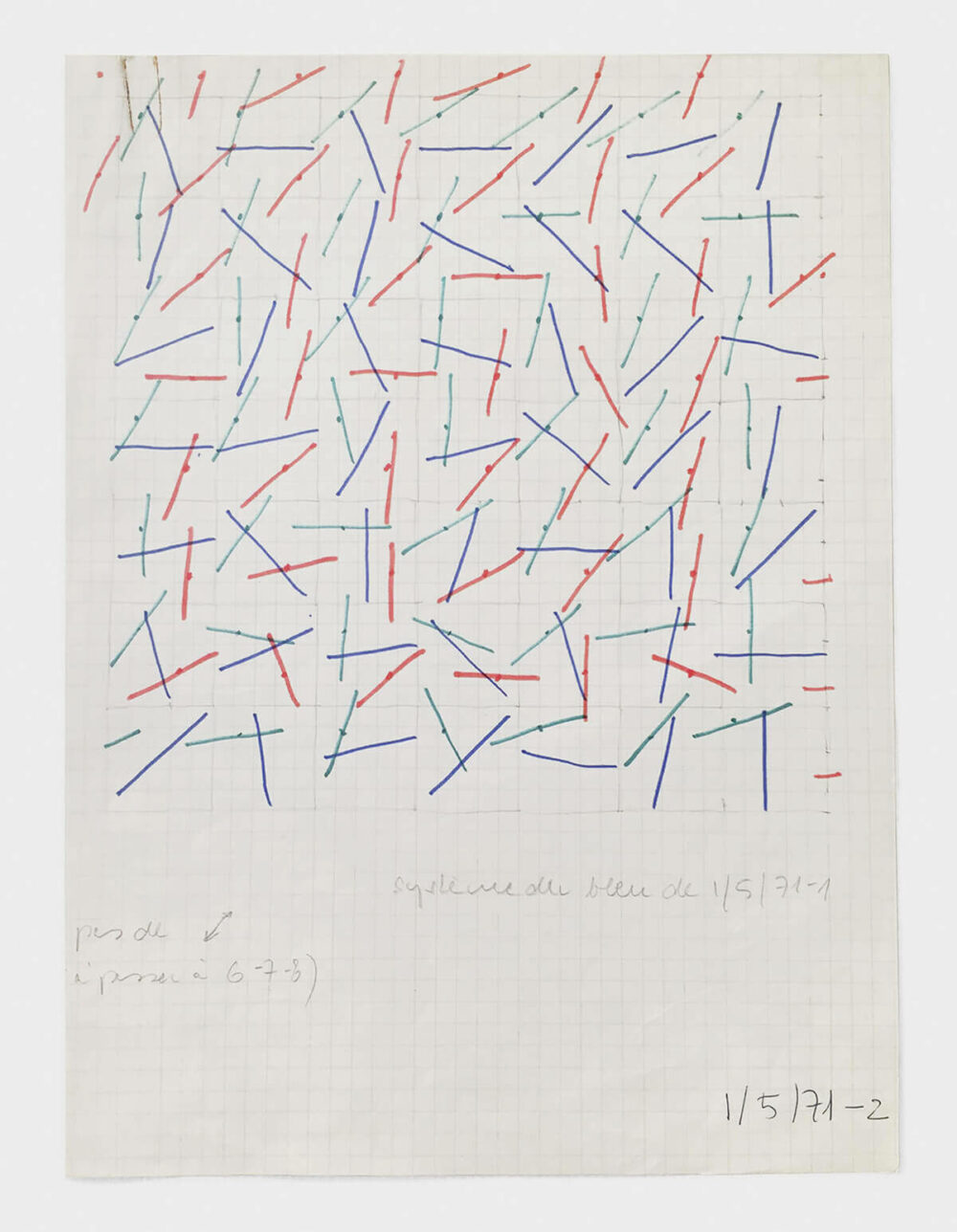

While Molnar did not begin her Journaux Intimes until 1976, she did hang onto her sketches for this work, which are framed alongside the plotter drawing at the Beall Center (the Spalter collection also includes two studies from 1969 and one from 1972). Of the two in this show, one is more obviously handmade, with red, green, and blue marks drawn with marker in a 7 x 7 grid structure, delineated by the artist herself in graphite on graph paper. Its wavering lines suggest that she drew the grid freehand. The other study is on tracing paper, the delicacy of which throws the different line qualities into sharp contrast: the thin blue marker appearing crisp alongside the thicker, runnier red and green that she accidentally smudged. Neither study, however, is identical to the plotter drawing. While they demonstrate that Molnar did work out ideas on paper, they do not establish a strict, linear relationship between hand-drawn sketch and computer-generated final product.

In fact, Molnar’s process involved a constant dance back and forth between paper and computer, between pencil and keyboard, and between images and alphanumeric commands. She worked — and continues to work — in a series of translations and transpositions across media.

Vera Molnar, Untitled (Study for Inclinaisons), 1971, ink and graphite on graph paper, 10.5 x 8.25 in. / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection

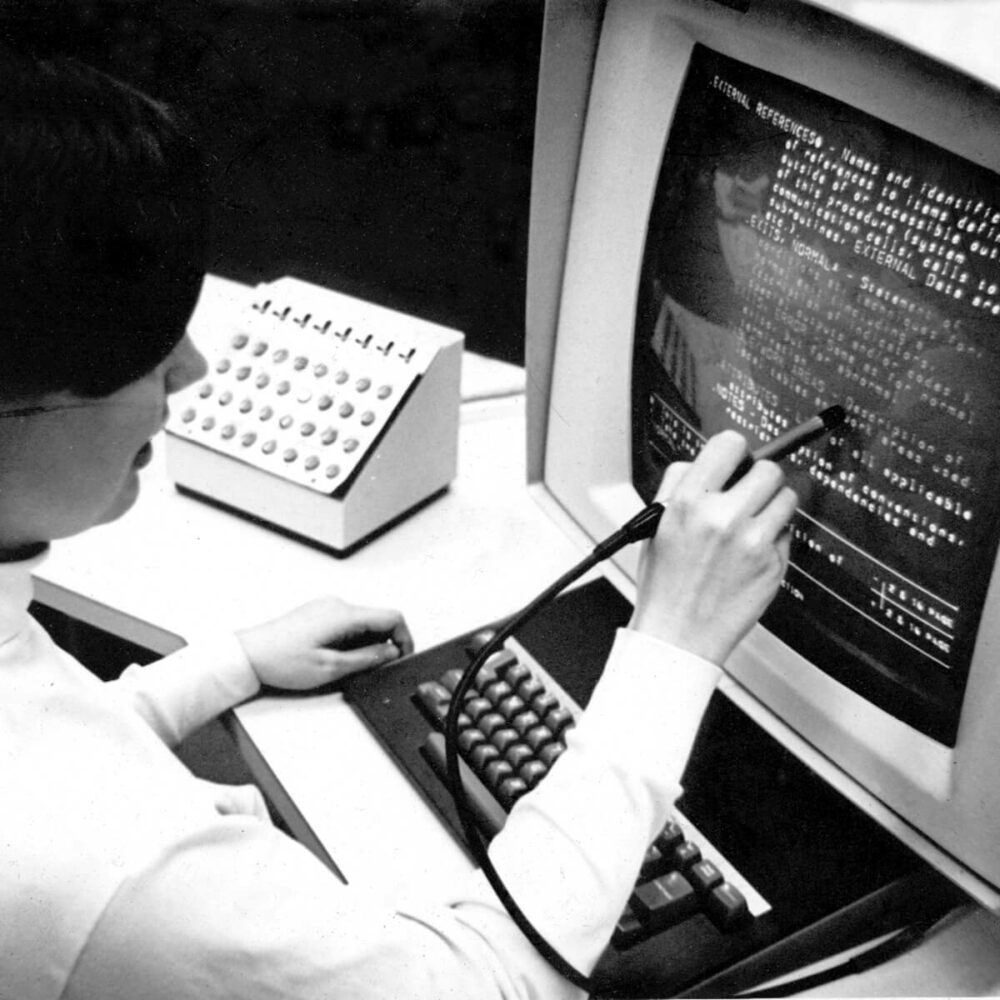

In 1974, Molnar came up with a term to describe her way of working. Writing for the journal Leonardo, she described her “conversational” method, always leaving the scare quotes around conversational.1 Why? My guess is that she borrowed the term from French computing discourse, where conversationnel referred to interactive computing. While blind computing involved a significant time delay between submitting instructions and receiving results, interactive computing happened in real-time. The site of interactivity was the computer screen, which served as an interface between the user and the computer. In fact, the introduction of the interface is when the user, in our contemporary conception of the term, was born. I argue in my dissertation that the advent of interactivity was the most significant milestone in Molnar’s career, though it’s been overlooked in both studies of her work and in the history of computing more broadly.2 When I asked her about the screen in our very first conversation, a shaky phone call in August 2017, I could hear her beaming as she said, “The IBM 2250!” She recalled her first time using the screen like a sort of rebirth, akin to moving to Paris at age 23. While I still don’t know for sure what year she first encountered the IBM 2250 (it was released in 1964, but there was usually a delay getting hardware to Western Europe; Molnar does not mention it in her writing until 1973), she remembers it with the kind of fondness usually reserved for an old friend.

“The site of interactivity was the computer screen. In fact, the introduction of this interface is when the user, in our contemporary conception of the term, was born.”

IBM 2250 Graphics Display Unit (1964), vector graphics display system by IBM for the System/360 / photo: Model IV display station, including light pen and programmed function keyboard (source: Wikipedia)

Output on-screen: Vera Molnar, photograph of an IBM 2250 computer screen showing a digital image from the series Inclinaisons, likely 1974 (collection of the artist)

Output on paper: Vera Molnar, plotter drawing from the series Inclinaisons, 1974, about 52 x 35 cm (collection of the artist)

Output on paper: Vera Molnar, plotter drawing from the series Inclinaisons, 1974, about 52 x 35 cm (collection of the artist)

“While I still don’t know for sure what year Molnar first encountered the IBM 2250, she remembers it with the kind of fondness usually reserved for an old friend.”

In 2018, leafing through a box of archival materials at the home of Molnar expert Vincent Baby, I stumbled upon these unmarked, black-and-white photographs of a computer screen. It wasn’t until 2020 that I found their plotter drawing counterparts at the artist’s studio, labeled, again, Inclinaisons, dated 1974. Another thread resurfacing in the Molnar textile. While these photos were never exhibited in an art context, they seemed to capture a moment Molnar did not want to forget.

So what was the conversational method? It employed not only a mainframe computer, but two key peripheral devices: the plotter and the CRT display screen, an IBM 2250 vector graphics display. She embraced the screen like few of her contemporaries did. Instead of waiting for the results of her program to be output to paper, she “[made] parameter changes quickly while viewing the images on the CRT screen.”3 This was not just about hardware. It also raises a fundamental question about process. Molnar’s results were emphatically not predetermined; they were always contingent on her subjective decisions.

Molnar’s text subtly points to the ways in which her method differed from others: “Whereas they begin with an initial set of rules (a grammar) specifying the way parameters are to be varied, I try to elaborate the rules as a work develops.” Her words recall debates about ‘tinkering’ that remain relevant to generative art today. Is it right for artist-programmers to mess with their results, their algorithms, or their programs? At what point do we call it ‘cheating’?

Some might say that Molnar cheated with the computer, an accusation I don’t think would upset her terribly. Maybe she did, depending on how you look at it. If you ask me, I’ll say that she was simply insistent on having the last word. Though I’m skeptical of her insistence that the computer was merely a tool for her, it’s true that Molnar never let it subsume her role as an artist.

Vera Molnar, Inclinaisons (1971) / installation view (frames on the right): The Beall Center

for Art + Technology, Irvine, California (US) / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection / photo: ofstudio

“Molnar’s results were emphatically not predetermined; they were always contingent on her subjective decisions.”

References:

(1) Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185–89. The text appeared in English. Molnar submitted the manuscript, written in French, to Malina in May 1974.

(2) Recent scholarship on early computer graphics largely comes from architectural history and media studies. See Matthew Allen, “Representing Computer-Aided Design: Screenshots and the Interactive Computer circa 1960,” Perspectives on Science 24, no. 6 (2016): 637–68; Jacob Gaboury, “The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen,” Grey Room, no. 70 (2018): 24–53; and Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, “An Ecology of Operations: Vigilance, Radar, and the Birth of the Computer Screen,” Representations, 2019, 86.

For earlier historicizations of interactivity, see sociologist Thierry Bardini’s Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000) and interaction and videogame designer Brenda Laurel’s Computers as Theatre, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1993.

(3) Molnar, “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines,” 187.

(4) ibid. The word “grammar” was included on the suggestion of Leonardo editor Frank Malina.