← Explore

Research: The Mechanical Arm of the Plotter

“In the early days, computing was a blind process. Artist gave instructions using punch cards but wouldn’t see the results of their program for hours or even days.”

“In the early days, computing was a blind process. Artist gave instructions using punch cards but wouldn’t see the results of their program for hours or even days.”

Zuse Graphomat Z64 flatbed plotter (1961), installed at DAM Projects for “Aesthetica” (2015). Molnar peer Frieder Nake cheekily argues that flatbeds are the only “real” plotters (conversation with author Feb 9, 2022).

“Even later works made using a screen couldn’t be shown in their native environment. The images had to be transposed to a more traditional art form: ink on paper.”

When we talk about ‘computer art’ from the 1960s and ‘70s, the actual shape and form it took looked quite different from most digital art made today. Nowadays, we’re used to viewing digital artworks—and most other artworks, frankly—on a screen, whether on a phone, laptop, or larger monitor. But this was not yet an option in the early days, when computing was still a blind process. This meant that the artist/programmer gave instructions using punch cards and couldn’t see the results of their program until it was output to paper, hours or even days later. When computer screens became more ubiquitous in the 1970s, they were still only accessible to people in computer labs. Even if an artist made work using a screen—as Vera Molnar did from the early 1970s onward—they still had to make hard copies, for these works simply couldn’t be shown in their native environment. In other words, the images had to be transposed to a more traditional art form: ink on paper.

These works-on-paper were not executed by hand, but by the mechanical arm of a plotter.1 Still, they became known as ‘drawings.’ Plotter drawings. For Molnar, this reliance on paper was not necessarily a limitation. It was a way to show continuity with her pre-computer works, which were programmed with the machine imaginaire but executed manually. For her, there was no fundamental difference between working with dice or combinatorial mathematics and working with an IBM system/370 mainframe computer. It was all “painting” to her.2 I want to point out, however, that the plotter allowed for considerable creativity. Molnar experimented with different kind of inks, even making some homespun inks out of beet juice and blood3—the wildest she would ever get—until she settled on a satisfying dark grey tone.

“I suggest we look at the nuances of these ‘drawings’ as an entry point for seeing the complex, iterative, nonlinear, and very hands-on process that was early computing.”

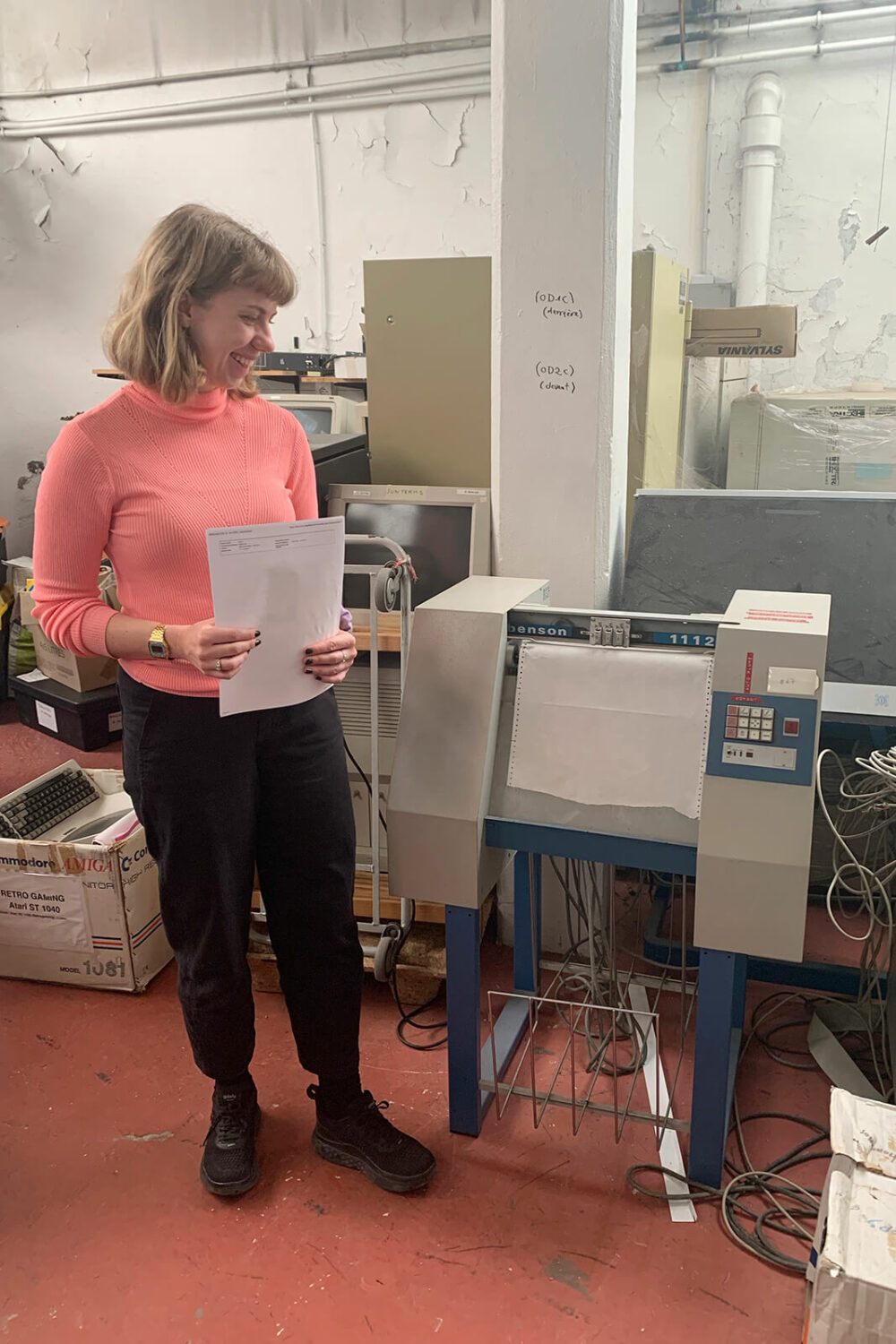

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy with a Benson 1112 drum plotter (1980 model) at ACONIT in Grenoble (FR), May 2022. Molnar would have used a similar, slightly earlier model in the 1970s. For scale, Zsofi is 5’7”, one inch taller than Vera was at the time. Molnar’s plotter would have been slightly wider. Photo by Xavier Hiron.

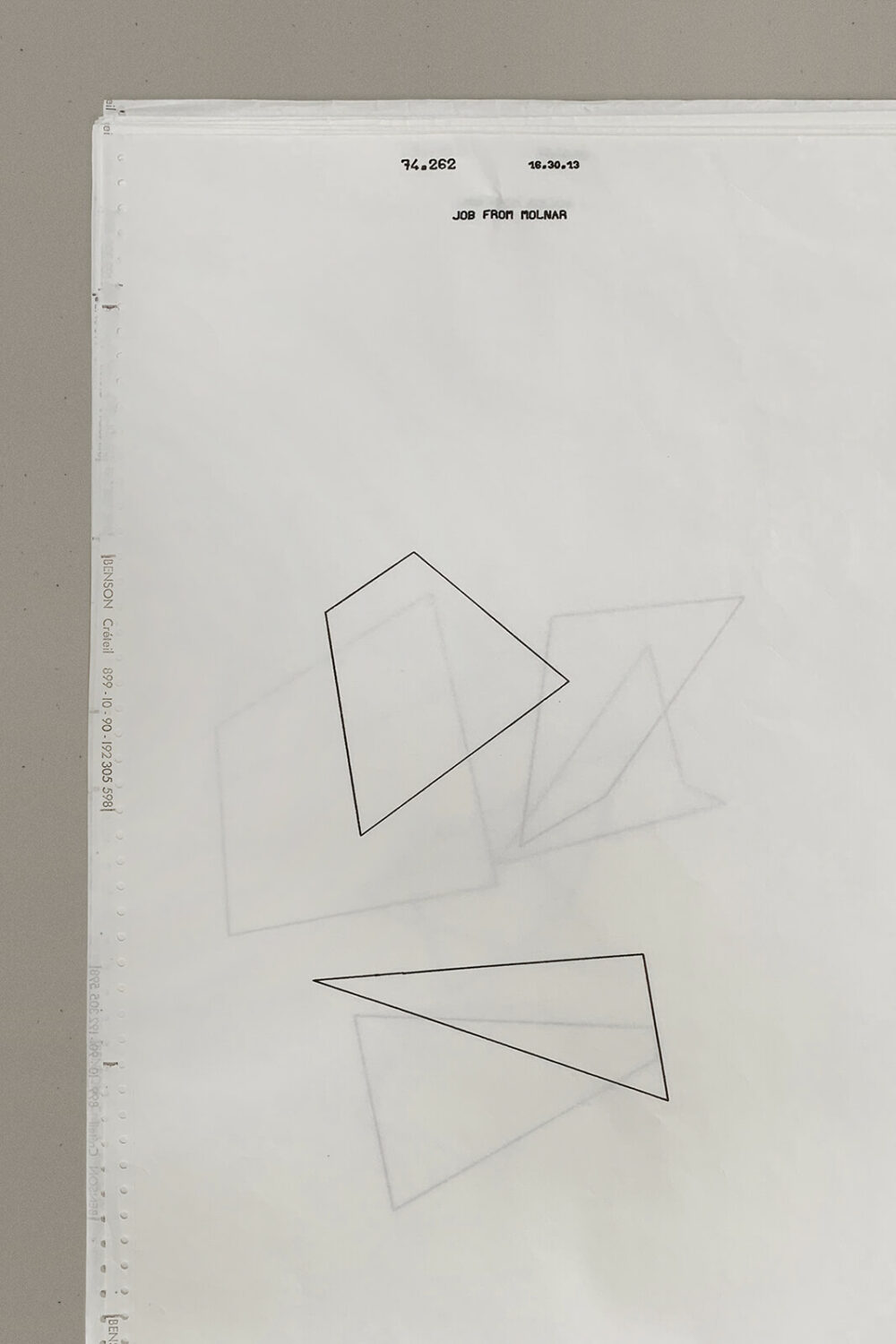

Plotter drawings from Molnar’s series Love-Stories (1974), on an uncut roll of drum plotter paper in the artist’s studio, Dec 2020. Each drawing measures about 54 x 36 cm. The thin paper allows for multiple variations to be seen at once. Photo by ZSVN.

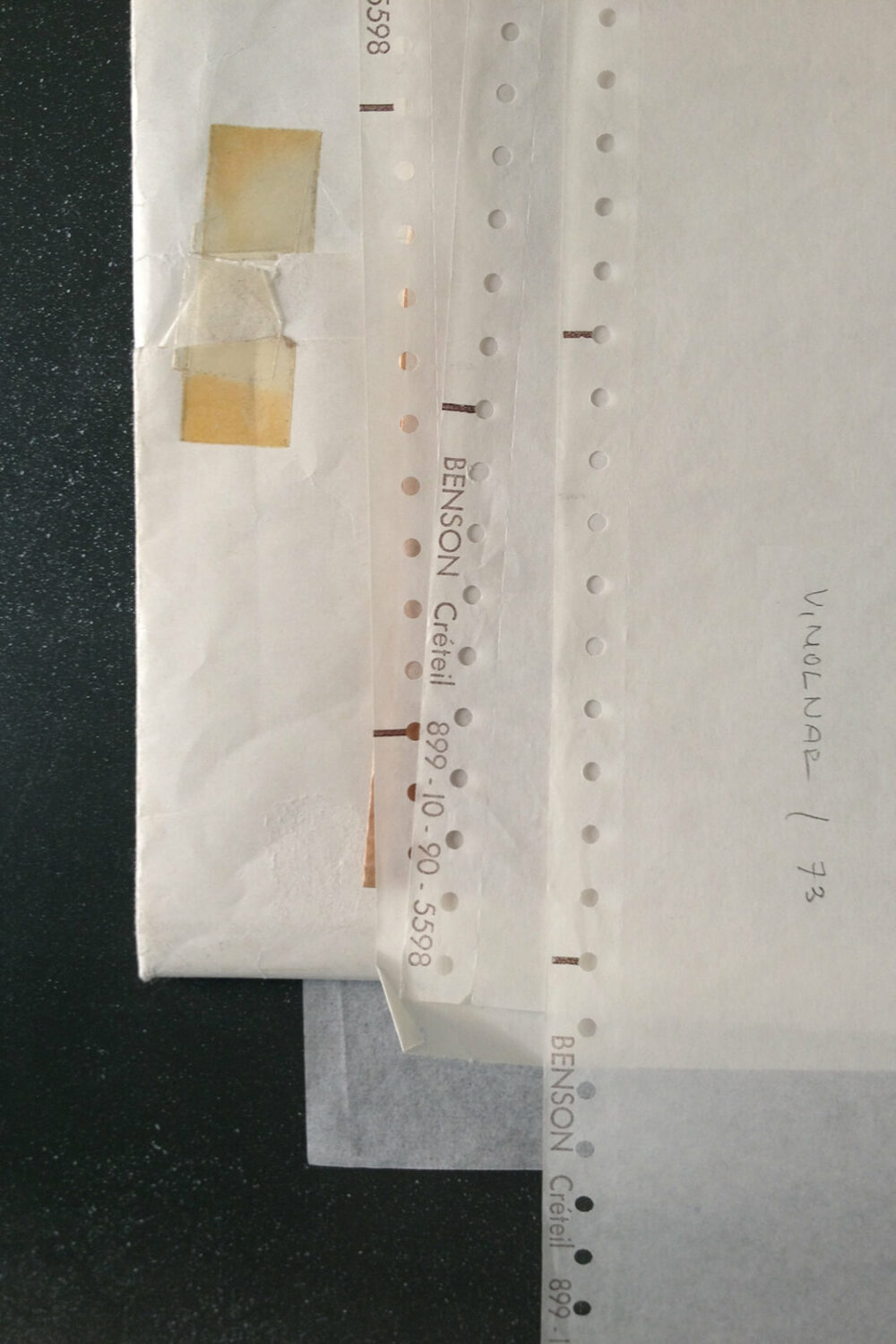

The distinct sprocket holes and BENSON imprint on many Molnar plotter drawings tell a story about their machine origins. Photo by Alexander Scholz, DAM Projects (2015).

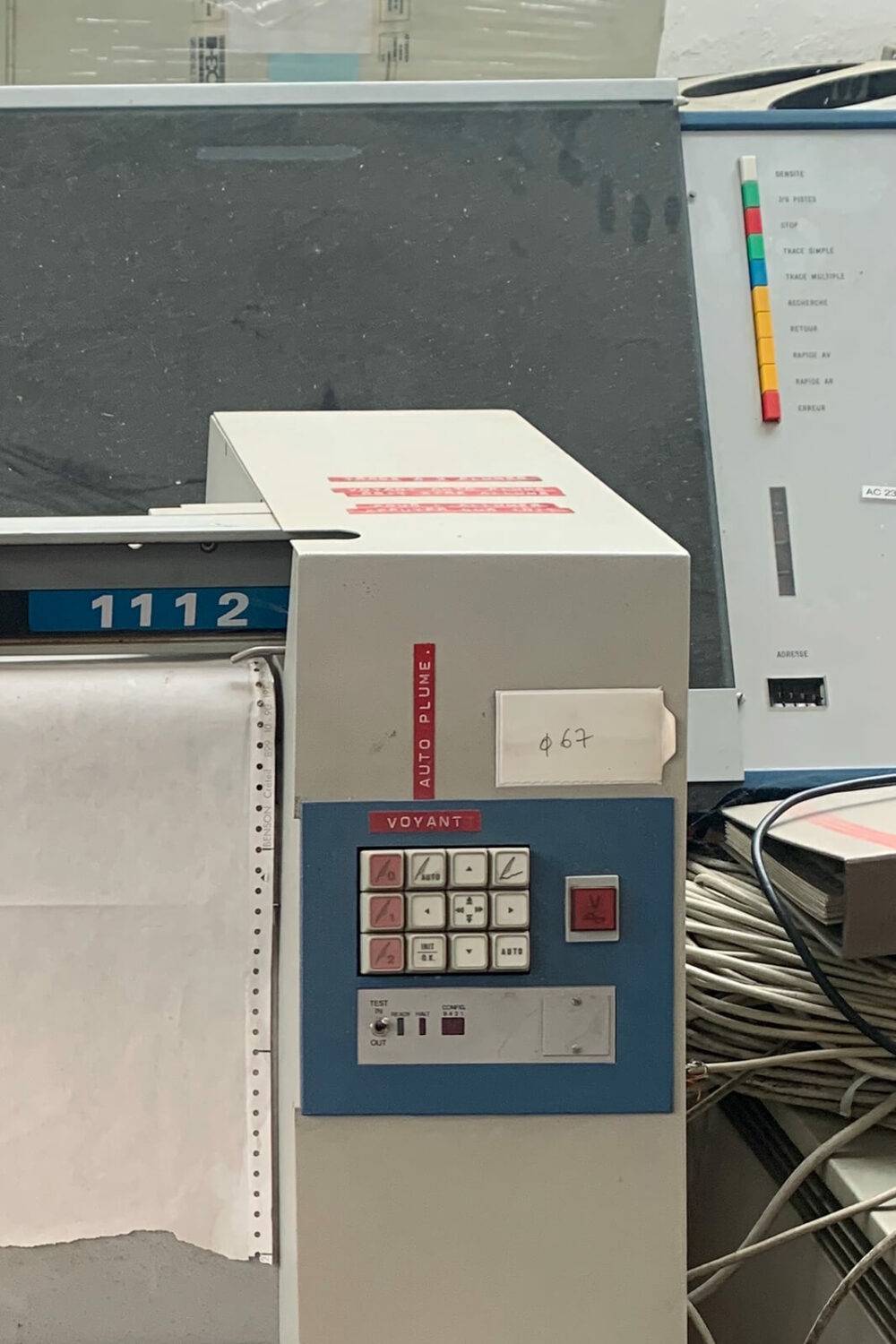

Benson 1112 drum plotter (1980 model), ACONIT, Grenoble (FR). Note that the BENSON imprint on the paper margins is the same as on Molnar’s 1970s works. Photo by ZSVN.

Molnar’s fellow digital art pioneers, including Manfred Mohr, who also worked in Paris, and Frieder Nake, a member of what is now called the Stuttgart school in Germany, also used plotters. But while Mohr and Nake used flatbed plotters, also known as ‘drawing machines,’ Molnar most often used the less glamorous drum plotter. Here’s the fundamental difference: with the flatbed plotter, the paper is stationary and the pen moves in both the x- and y- directionl the operation looks a lot like the human process of drawing, only it’s done by a robot. The drum plotter less so: its pen moves on the x-axis while a roll of paper is fed through in the perpendicular direction. This is why many of Molnar’s works have sprocket holes along the sides. Drum plotter drawings tend to have a more ephemeral quality because the roll mechanism required a very thin, almost transparent paper—by contrast, the flatbed could handle nicer, thicker paper. Perhaps Molnar liked the drafty quality, but my guess is she preferred the drum plotter because it was better suited to serial output: she could plot one variation after another in succession, without having to switch paper.

The ink-on-paper format is perhaps what has allowed art museums to collect this work more extensively than other forms of digital art, as we don’t need to reactivate obsolete technologies to view it. But its deceptive straightforwardness also runs the risk of flattening our understanding of early computational art into a simple process of input and output. I want to suggest we look at the nuances of these ‘drawings’ as an entry point for seeing the complex, iterative, nonlinear, and very hands-on process that was early computing.

“The ink-on-paper format has perhaps allowed art museums to collect this work more extensively than other forms of digital art, as we don’t need to reactivate obsolete technologies to view it.”

References:

(1) See contemporary generative artist Sher Minn Chong’s talk “Recreating Retro Computer Art,” and read her historical overview of plotters here.

(2) See Molnar, Vera. “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer.” Leonardo 8, no. 3 (1975): 185–89. My intention is not to equate painting and drawing, but an exploration of the rich historical relationship between them is outside the scope of this note and will be addressed in my dissertation.

(3) Molnar also told this story to Hans Ulrich Obrist: “Vera Molnar in Conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist.” In Bookmarks: Revisiting Hungarian Art of the 1960s and 1970s, edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist and András Szánto, 76–87. Koenig Books, 2018.