Field Guide

Accessibility, Resilience, Sustainability:

Upgrading Our Cultural Infrastructure

Whether art, theatre, music, or film—festivals are vital nodes in the cultural nervous system. It’s where new ideas are first injected into the discourse; where they travel, mutate, and multiply, before they seep into the wider public consciousness. For the devoted audience, festivals are pilgrimages that rejuvenate the soul and reaffirm one’s love for art and music. For those that make them happen, festivals are a way of life—and a constant struggle.

Keeping cultural infrastructure not only intact but vibrant, requires more than keeping pace with trends, audience expectations, and shifting norms. Beyond perennial concerns like programming, funding, and the role of the festival in the ever-changing cultural landscape, there are existential questions about virtuality and sustainability raised by the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis. How can festival makers simultaneously build resilience, expand accessibility and inclusion, while minimizing the environmental footprint of cultural production? And what would a future festival that overcomes these challenges even look like?

This much is clear: None of these questions can be answered by one isolated festival. That’s why Future Festivals, a research project funded by the Canada Arts Council, assembled a task-force of festival makers from Canada, Germany, and Mexico to collaboratively imagine how their work might evolve in the years and decades ahead. Under the helm of curator and cultural researcher Maurice Jones, representatives from MUTEK (Montreal, CA), imagineNATIVE (Toronto, CA), Mois Multi (Quebec City, CA), MUTEK Mexico (Mexico City, MX), New Forms (Vancouver, CA), NEW NOW (Essen, DE), and Send+Receive (Winnipeg, CA) will put their heads together to explore what forms festivals can take in the years ahead. The selection is no accident: these organizations can draw on distinct curatorial agendas, communities, geographies, and in many cases decades of institutional memory. It’s not a closed group either: if you and your organization are interested in joining the project, then please get in touch!

Over the next 18 months, starting with NEW NOW in Essen (June 1-4), each participating festival will host a Future Festivals Lab that gathers the group and selected experts around a key challenge. The goal: deeply analyze shared problems and prototype solutions—from immediate, easy to implement measures to more ambitious, long-term proposals.

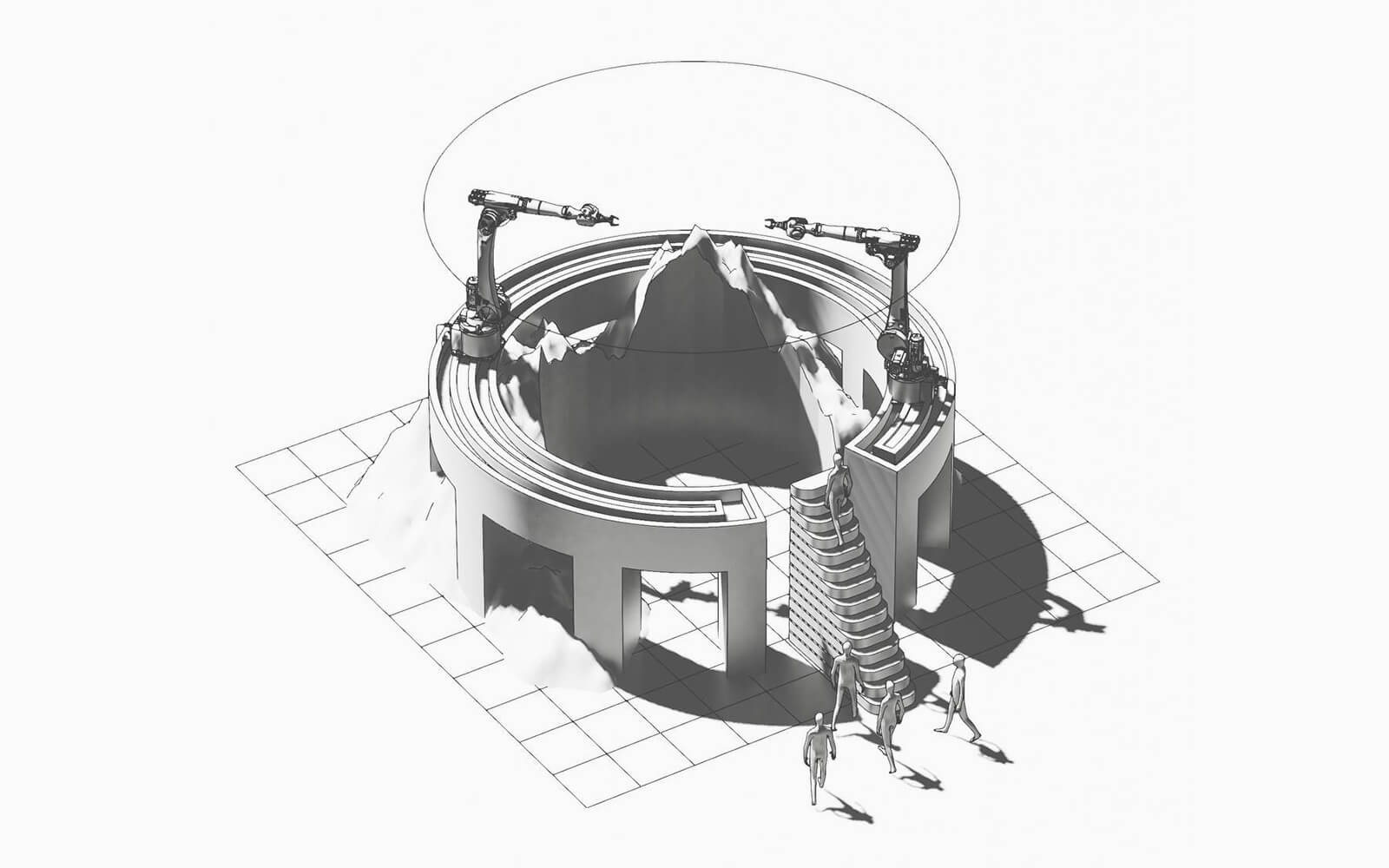

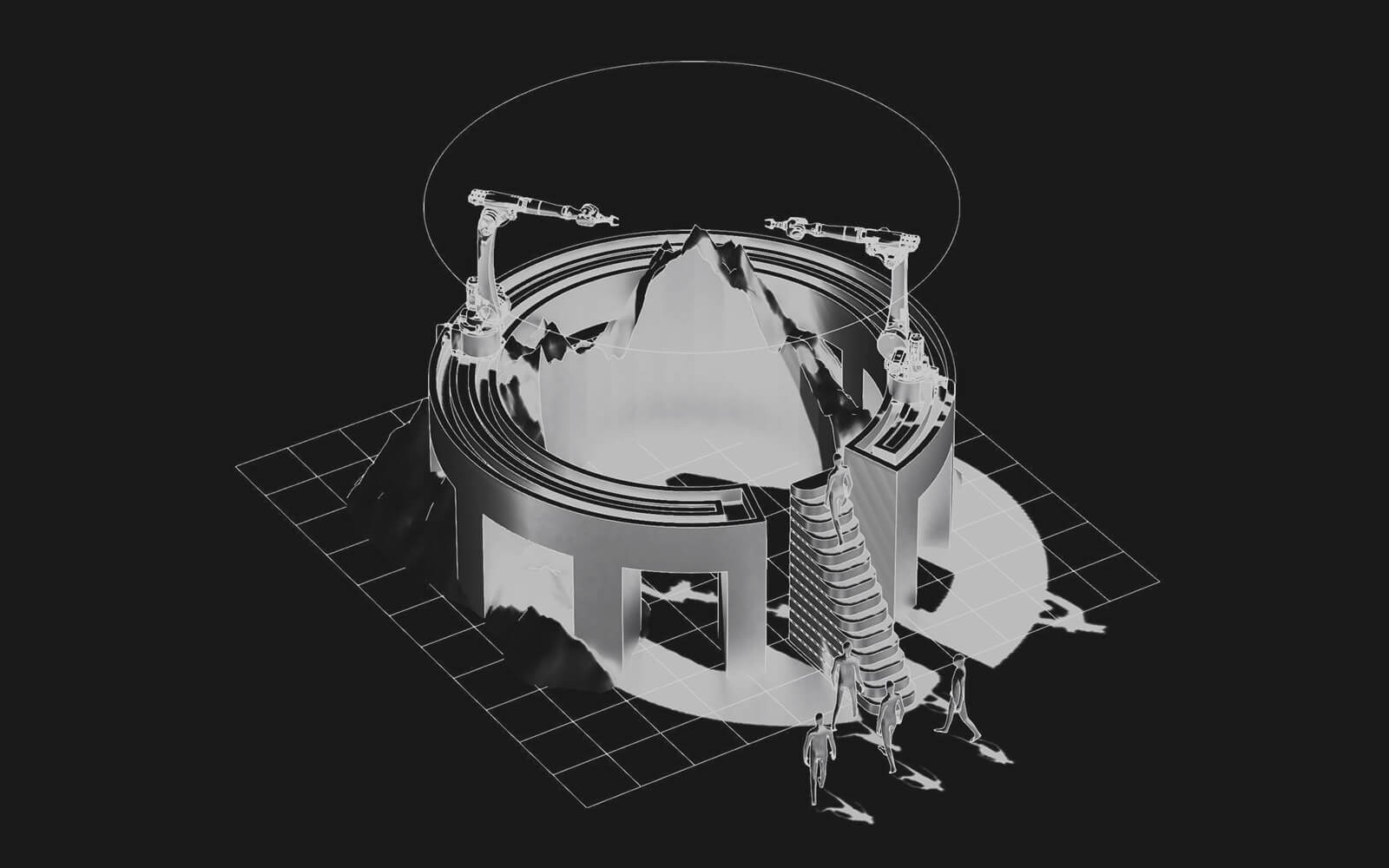

HOLO will file reports from these sessions in what we call the Future Festivals Field Guide, an expanding companion dossier that follows the project from start to finish. As embedded journalists, we will document the group’s progress, share key findings and outcomes, and bring important guest voices into the conversation. But the scope of the Future Festivals Field Guide goes beyond coverage and commentary: Together with N O R M A L S, a Berlin-based design fiction collective and trusted HOLO collaborator, we will build on the ideas produced in each lab session and ‘act them out’ in speculative scenes—mockups of a future festival—for you to explore.

Needless to say, we at HOLO have a vested interest in the future of the festival circuit and the wider cultural landscape around it that we consider ourselves very much a part of. We look forward to not only reporting from the frontlines of that future, but to actively help shape and contribute to it. Stay tuned!

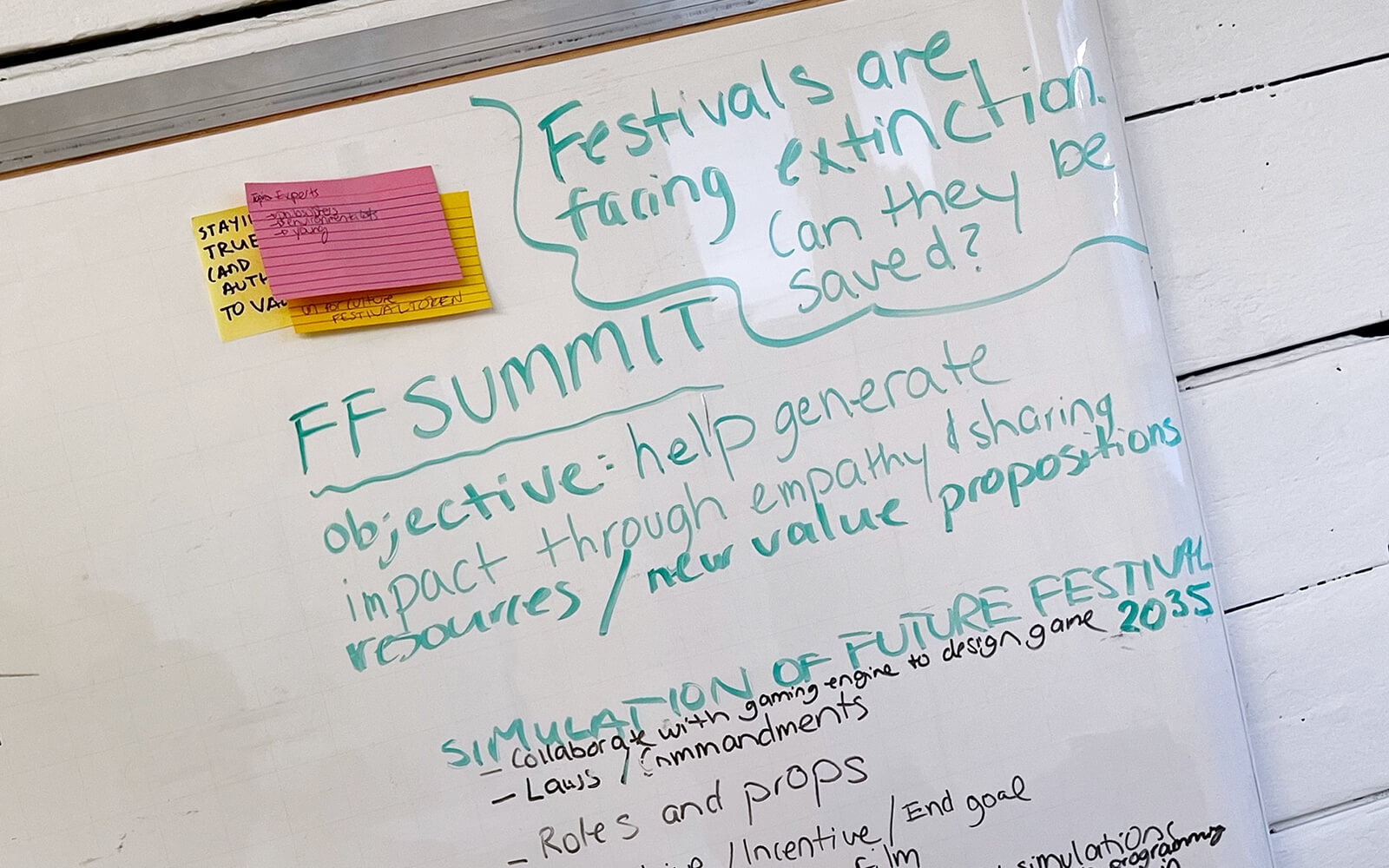

If upgrading our cultural infrastructure—the declared goal of the Future Festivals group—sounds like a daunting undertaking, try doing so within just 18 months and a group of traditionally overworked festival makers. How do you prototype festival futures with organizations from three different continents, all working at different scales, serving different communities with different needs? How do you settle on issues to tackle when challenges around access, resilience, and sustainability compound and overlap? Where do you even begin?

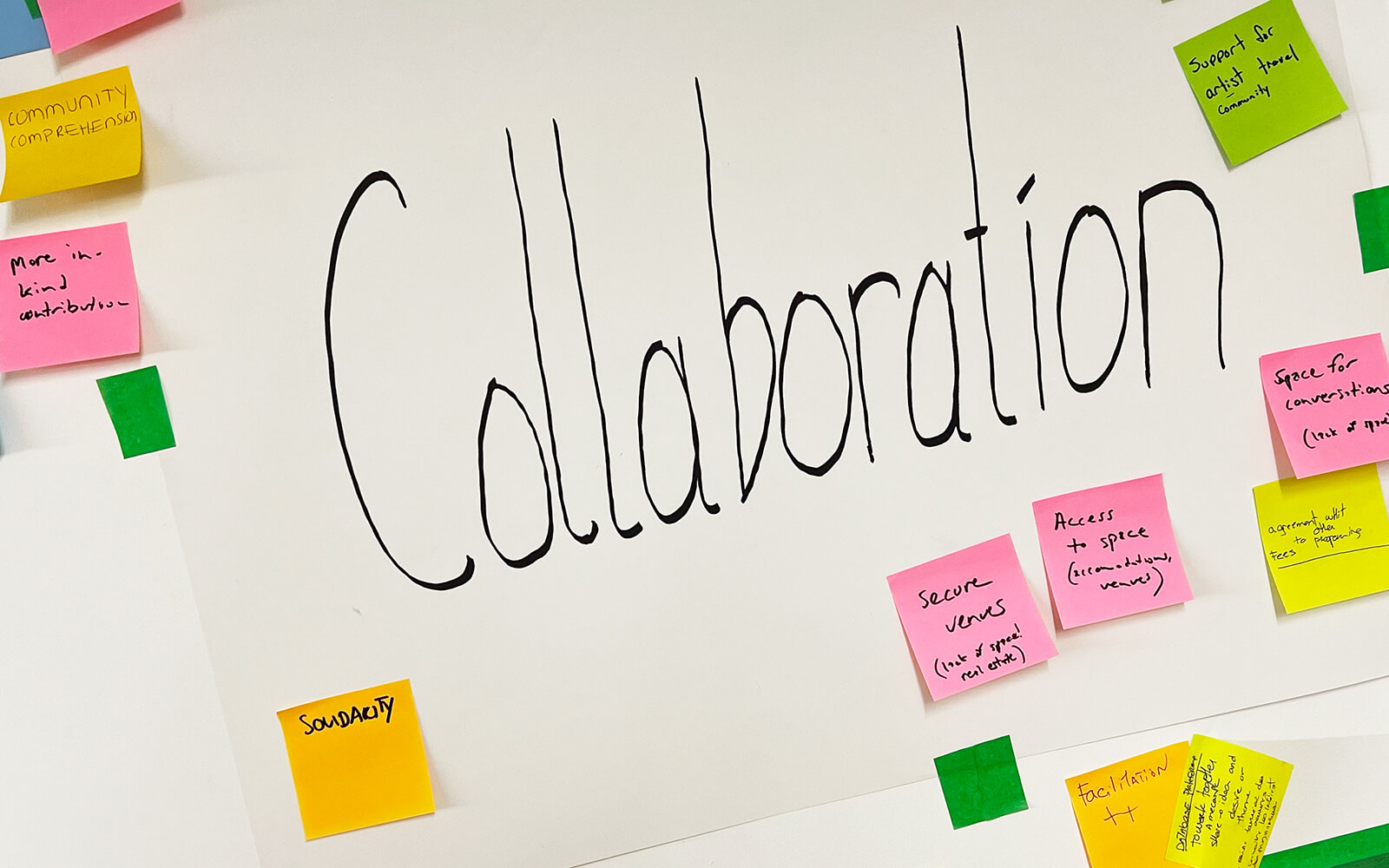

Thankfully, MUTEK co-curator and Future Festivals project lead Maurice Jones provided starting points and the necessary structure. Between April and May of 2023, he invited representatives of the partnering festivals to a series of online workshops designed to feel out an agenda. Starting from a place of “care, active listening, and generous questions,” festival directors, programmers, and operations team members gathered over Zoom to identify shared struggles and chart pathways to possible solutions. The stated goal: “develop a joint purpose and vision” while “providing space for the specific needs, contexts, and topics of each partner.”

To steer the conversation away from mere group therapy—yes, there was much needed venting about lack of funding, space, and capacity—and to a more productive mode of discussion, Maurice prepared a simple but effective exercise. Drawing on the aptly named Three Horizons model, a methodology first proposed in David White’s The Alchemy of Growth (1999), Jones asked participants think about festivals across different timelines: the present, the far future, and an interstitial in-between. Imagining the latter, Maurice explained, is key to discovering incremental steps that, over time, will pave the way for new modes of cultural production. To identify viable, near-term measures, however, we’d first need to be candid about current challenges and, conversely, dream big.

Unsurprisingly, the group’s critique of present festival realities echoed many perennial concerns within the cultural sector: the existential angst that comes with dwindling (or non-existent) public funds, the loss of affordable spaces to an out-of-control real-estate market, the exhaustion felt by cultural workers still reeling from the COVID-19 system shock (and its frenzied pivot online). Important issues like expanding accessibility, better community involvement, and lowering the environmental footprint become insurmountable when you operate at the edge of precarity.

Asked to counter present challenges with festival utopias, the group pondered everything from universal support structures to simple acts of solidarity. What would festivals look like, if artists and cultural workers could rely on UBI-like financial support that eliminates fears of precarity? And what if, instead of competing with one another, festivals would collaborate, share resources and commit to common goals? And wouldn’t it be nice if festivals were green as a first principle, offered respite from neoliberalism’s obsession with productivity, and were accountable to the public, not just funders?

Over the next 18 months, the Future Festivals group will try and produce concrete proposals that address some of these questions. The following list of themes and speculations will serve as our guide:

Present: The COVID pandemic prompted some overdue soul searching about who has access in the cultural sector. While the recognition of disability rights and experimentation with hybrid programming has lowered some barriers of entry, a lot of work remains to be done.

Future: Venues, content, communication—festivals lead by example when it comes to bringing different people together. They exceed mandated accessibility standards, accommodate the vision and hearing impaired, and include remote audiences with next-generation, mixed-reality formats.

Present: Countless hours of invisible labour go into compiling reports that are privy to funders, not audiences or the public. Direct communication with the community is largely limited to promotion (via stingy social media platforms that throttle visibility) and awkward surveys.

Future: Directly reporting to global audiences and local stakeholders radically increases transparency and community investment. Taking cues from the decentralized autonomous organizations (DAO) and community curation initiatives in Web3, festivals create more pathways for direct input.

Present: Compared to industry, culture workers perpetually have to do more with less—less money, staff, time—and largely live project to project. This leads to widespread fatigue and burnout, high staff turnover, and a steady ‘brain drain’ of talent leaving the sector.

Future: With more—and more reliable—support, organizations can chart long-term strategies on how to serve their community better. No longer overburdened and generally happier and healthier, staffers are able to build capacity, and train the next generation of cultural workers.

Present: In the never-ending race for limited attention and funds, galleries, festivals, and cultural organizations tend to view their peers as competition. The result: knowledge and resources are hoarded, leaving communities fractured and both staff and audiences overwhelmed.

Future: Aligned around common values, festivals and cultural organizations team up and share resources whenever they can. Collaborations allow knowledge transfer across teams, and pollination between fields and communities. They’re also a way to play and experiment, and keep audiences on their toes.

Present: The pandemic revealed and exacerbated a growing sense of social alienation that culture—festivals in particular—may just be the antidote for. But who gets to participate in the communities they foster? The truth is: More often than not, festival makers cater to privileged international niche audiences, while sometimes overlooking immediate neighbours and entire demographics.

Future: Festivals double down on local ties, forging deeper and more meaningful connections with the communities they take place in. Children, seniors, families, newcomers—a wave of fresh energy and perspectives flows into the mix, increasing diversity and expanding audiences.

Present: Organizations are in fierce competition over dwindling public funding or at the behest of corporate money. Grants that are progressively project-based (versus operational) tend to increase workload not capacity. Worse yet: skyrocketing real-estate prices force orgs and cultural workers out of the neighbourhoods they have enriched for decades.

Future: With UBI-like baseline support, artists and cultural workers can create without fear of precarity. Festivals and organizations have (easier) access to operational funding and rent subsidies, can generate revenue, and purchasing permanent facilities is feasible. Membership models and (ethical) private sector sponsorship add to the resilience.

Present: From energy and resource-intensive blockbuster shows to flying bodies and gear around the world—the environmental footprint of cultural business-as-usual is untennable. According to a 2020 study, the 184 organisations in the Arts Council England portfolio emitted 114,547 metric tonnes of CO2 in 2018/19 alone.

Future: Environmental considerations shape cultural programming, rather than being an afterthought. As innovators, festivals lead the charge in telepresence, circular exhibition and event practices, and offer pluralistic responses to any of the ugly sociopolitical consequences—migration, xenophobia, ultranationalism—the climate crisis may unleash.

The Future Festival visioning sessions were more than a temperature check and speculation. They provided a rare opportunity for cultural workers to be vulnerable, to speak openly and candidly about their struggles, and share some successes, too. From experimenting with PWYC (pay-what-you-can) models, to next-generation mentoring initiatives, to radical accessibility programs that include seniors and kids—there’s no shortage of promising trials for the group to learn from and build on over the coming months. A critical selection will be catalogued here.

Another lesson we took away from the sessions is the need for advocacy. As vital nodes in the cultural nervous system, festivals have to make a better case for themselves. All too often, the value that culture creates for society only becomes apparent in its absence—when spaces close and festivals die, or during the cultural winter of the early pandemic. Festival makers need to remind the public and stakeholders of their role and contributions in order to secure support and allies. Alain Mongeau, MUTEK’s founder and artistic director, compared building these lasting relationships to taking care of plants. “You need to water them regularly,” he said during one of the sessions. “You have to constantly seed ideas to align people and make them more receptive to your needs.”

Maurice Jones is a curator, producer, and critical AI researcher based in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal, Canada. As a Concordia University PhD student, he investigates cross-cultural perceptions of AI, public participation in technology governance, and festivals as methodology. He’s the Artistic Director of MUTEK.JP and in 2021 joined MUTEK’s Montréal headquarters to spearhead the AI program and Future Festivals think tank.

Through the MITACS-funded sub-project Festival as Methodology, a collaborative effort between Concordia University and MUTEK, I propose the art and technology festival as a potential site for developing new, more equitable, diverse, and inclusive forms of public participation in the shaping of AI and technology more broadly.

While the Future Festivals project has a far broader scope than my specific research interest as it is driven by our partner cohort, I believe there are two fundamental questions that we all try to understand better: 1) what is it exactly that happens during festivals that makes them spaces of valuable and transformative experience; and 2) how can we leverage these transformative potentials in multifaceted ways to drive social change?

Despite this heterogeneity of partners, the two month co-design process crystallised that there are common concerns and challenges surrounding questions of accessibility, accountability, capacity, funding, inclusivity, and sustainability shared to some degree between all partners. One of the challenges of this project is then how to address these common issues in a practical manner that is aware and respectful of the situatedness of each partner.

Overall the project is centred around openness and co-creation. We already extended our outreach beyond the original partner cohort and are excited for more people to join the conversations. The upcoming MUTEK Forum in Montreal end of August will focus on expanding the conversation even further to the broader public and the about 50+ cultural delegates that come to visit Montreal each year.

A concrete example was the emphasis we laid on diversifying our lineups starting 2018 inspired by international projects such as Keychange and Amplify. For the third edition of MUTEK.JP we initiated a EUNIC-funded project highlighting the underrepresentation of women and members of the LGBTQ+ community on festival stages and within the cultural sector. In a country that just fell again on the gender gap to place 125 earlier this month, pushing these conversations in our conference program and highlighting underrepresented artists on our festival stages continues to mark a stark intervention.

While there are certainly many factors that play into transformation, the impact of our activities on at least our surrounding milieu was felt. Many conversations with cultural professionals were held and lineups of club nights and other festivals markedly took note in diversifying their lineups as well.

Q: Beyond the cultural shutdown (and shift to digital and hybrid events) that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, what other recent developments in the cultural sector make you think Future Festivals is a necessary and timely project?

A: The co-design process found that across the board there appears to be an increasing precarity of cultural work, which was accelerated by the pandemic and really just now comes to the forefront with all COVID-related relief measures waning off. Inflation is rising and budgets are cut. Spaces become scarce. Cultural workers, those who actually remained in the field after the pandemic, are notoriously overworked and underpaid. In many ways this project could also be framed as: Is there a future for festivals?

At the same time culture in the public mind is expected to be vibrant and engaging. It is what makes cities like Montréal so attractive to people. The work and the labour that goes into making these things happen goes mostly unnoticed. Future Festivals then also becomes about finding better ways to advocate for the work that we as festival makers do and why it is important. One such way might be looking at festivals and culture more broadly through the lens of mental health and well-being rather than through a consumerist perspective looking for entertainment.

First, Future Festivals as a platform of sharing knowledge around best practices of festival making. There are many projects and experimental case studies that festivals around the world already engaged in. Without reinventing the wheel, how can we mobilise this sort of knowledge to benefit festival makers across the board. As Naomi Johnson from imagineNATIVE put it eloquently, we should foreground what we can give rather than what we can take.

Second, I hope that Future Festivals becomes a vehicle for advocating for the work of festival makers, for making more present the challenges we face and that culture more broadly doesn’t just magically appear. The HOLO Future Festivals Field Guide plays a crucial role in both these endeavours.

Finally, I believe that the project itself and how it unfolds in an open and exploratory way is already an experiment in prototyping new ways of cultural production—a sort of learning by doing, which will hopefully inspire other festival makers to jump on board or initiate conversations within their own cultural ecosystems.

The agenda mapped out by the seven festivals currently part of the Future Festivals group was only ever intended to be a starting point, a first pass at identifying the top-level issues that ail the cultural sector. There’s broad consensus on expanding access, equity, and sustainability, for example, but noble goals rarely square with existential needs. The truth is that the on-the-ground realities of festivals are often complicated, and individual circumstances differ greatly even within the same region (or city). Many more festival makers have since joined the discussion, but we’ve only begun tap into the myriad perspectives this project could and should surface. Besides, it’s not only festival makers who make a festival. Artists and audiences are the lifeblood of the festival circuit and, more often than not, swing the balance towards success or failure. Shouldn’t they, too, have a seat at the table when the future of festivals is being discussed?

With the Future Festivals Survey, we invite all stakeholders—curators, cultural workers, artists, and festival goers—to chime in about the state of our cultural infrastructure. What do you think the role of festivals is, or should be, in your community? In which areas do festivals deliver for people and where do they fall short? And does it matter how and by whom they’re funded? Over the coming months, we plan to map the cultural needs and wants across regions and communities to guide us and other festival workers into the future. And the more participants we hear from, the more complete the picture. Whether you attend them for work or pleasure, whether they champion music, theatre, art, or film—if festivals are a part of your cultural diet, please take a moment to support our research by adding your voice to the conversation. Thanks!

The survey is available in English, French, and Spanish. It collects demographic details, personal opinions, and offers opportunities to get involved. The results will be published at the conclusion of the Future Festivals project.

Post-Industrial Imaginaries

Withering machine giants from a bygone era, chutes and pipes that extend as far as the eye can see: Embedded in over 100 hectares of decommissioned mining infrastructure, the first Future Festivals Lab couldn’t have taken place in a more dramatic setting. Zeche Zollverein in Essen, Germany, was once the epicentre of European fossil fuel production. Now, it’s an open-air museum of 19th and 20th Century industrial architecture and revered as a national treasure. The highlight: the iconic winding tower of shaft 12 that looms large at the complex’s centre. At 55 meters tall, the steel structure locals affectionally call the region’s Eiffel Tower is considered a 1920s engineering masterpiece and the reason for Zollverein’s reputation as the most beautiful coal mine in the world. So beautiful, UNESCO declared Zollverein a World Heritage Site in 2001.

During its peak, between the two World Wars, Zollverein employed more than 8,000 miners and extracted 3.2 million tonnes of coal per year. Today, the only things produced at Zollverein are art and culture. After the mine’s closure, in 1986, a plan was devised to preserve the site’s unique architecture and put it to public use. Now home to several museums, theatres, and more than 150 creative businesses, it is a bustling hub of cultural activity and an example of post-industrial redevelopment for the entire region.

Our host, NEW NOW, is the latest and, perhaps, boldest attempt at bridging Zollverein’s past and future. Launched in 2021 under the stewardship of artistic director Jasmin Grimm, the biannual digital art festival leverages nascent technologies and emergent creative practices to reflect on the site’s legacy and ask urgent, vexing questions: What can a former coal mine teach us about the belief systems and power structures that prop up past and present regimes of extraction? What are the true costs—social and environmental—of ‘inevitable’ technologies; who stands to benefit at whose expense? And how do we break the delusional cycle of infinite economic growth before the planet hits its boiling point?

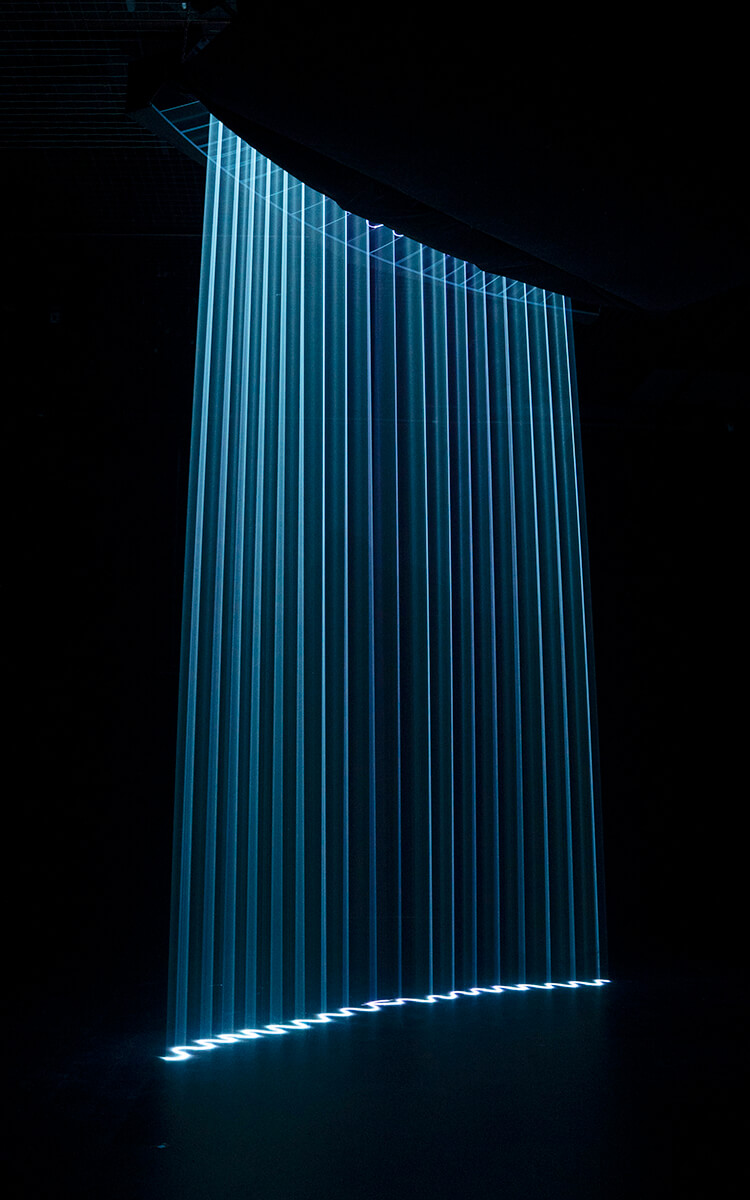

During the festival, NEW NOW seeks answers in discursive formats that bring artists, theorists, policymakers, and the public into conversation. But what sets the tone are months of artistic experimentation: For every edition, NEW NOW invites a cohort of seven resident experts working with new media—code, videogames, robots, AI—to explore a central theme with new creations. The brief: engage with the site on a deeper level and engineer forward-looking, hopeful visions in response. At the inaugural “Another End is Possible” edition, for example, a solar-powered satellite (Kimchi and Chips, Another Moon) rose over Zollverein at night. Cast with lasers that reenergize during the day, it signalled a future after fossil fuels.

This year, NEW NOW doubled down on hope with a dose of eco-fiction. Under the evocative theme of “Hypernatural Forces,” the residents conjured cyborgian encounters where, rather than being at odds, technology and ecology amalgamate into one. Once the domain of heavy-duty machinery, the concrete caverns of Zollverein’s Mixing Plant were now habitat to feral robot dogs (AATB, Spare Pack), shimmering e-waste flora (Sabrina Ratté, Inflorescences), and AI fungal infestations (Daniel Franke, Gan Chimera). The people were mere guests, no, alien visitors in this environment, curiously probing for life signs in contaminated soil samples (Eva Papamargariti, All that is hidden) or tuning into the songs of synthetic plant intelligences (Jana Kerima Stolzer & Lex Rütten, Neophyte). They teleported into threatened treetops (Haha Wan, Would you would you would you••••••) and zoomed into the deep time aeons compressed into coal (Pınar Yoldaş, Time Tunnel).

We’re already surrounded by ‘hypernature,’ Grimm noted during NEW NOW’s opening. Large parts of the planet, including its atmosphere, are heavily geoengineered. Entire ecosystems have been irrevocably changed. Our concept of ‘the environment,’ too, is technologized: Without satellite data and atmospheric sensors, we couldn’t measure CO2 or air pollution; without supercomputers, there would be no climate models. The term hypernature, Grimm explained, borrows from the supernatural and Jean Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality, where constructed or simulated worlds take precedence over the ecosphere. It describes a post-natural condition that acknowledges that there’s no return to a mythical state of purity. Instead, it offers hope that we may live with our toxic legacy and cultivate new ecologies going forward. The implants at Zollverein’s Mixing Plant indicate as much. Like pioneer species reclaiming de-natured space, they erode and break down the binaries of a bygone era, allowing alternate worlds to emerge from the rubble.

The first Future Festival Lab, too, invited introspection: Beholden to funders and the attention economy, aren’t we festival makers perpetuating extractive practices and growth as a metric of success? Can art and music survive (or thrive) outside platform hegemony? And what would festivals look like if we curbed production excesses and focused more on what our communities really need?

Focus: media art, sound, performance

Location: Zollverein in Essen, Germany

Launch: 2021

Frequency: biannual

Visitors: ~10,000

Team: 10 plus Zollverein staff

Structure: NPO (nonprofit organization)

Funding: public via the Ministry of Science & Culture NRW

Formats: conference, exhibition, performances, workshops, residency and regional satellite program

Jasmin Grimm is a German-Algerian curator and creative entrepreneur. She is the founder and artistic director of NEW NOW Festival. Prior, she has directed programs for NRW-Forum, Goethe Institute, Bitkom, the Competence Centre for Cultural & Creative Industries of the German Federal Government, Retune Festival and TINCON. She was a programme advisor for the Kulturstiftung des Bundes, Futurium, Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia. (Photo: Constanze Flamme)

Positioning a new festival in this context is an exciting challenge. How do we build new cultural infrastructures in times of environmental breakdown and vanishing resources? How do we create a space that offers a hopeful vision for the future? What can we contribute and whose voices should we amplify? We ask ourselves these questions all the time.

Q: The Future Festival Lab at NEW NOW explored sufficiency—the suggestion that rather than perpetually maximizing output, we focus on essentials and cultivate content within those means. As a festival that activates not only Zollverein site but the rentire egion, where do you think NEW NOW could do more with less?

A: I really love sufficiency as a path towards sustainability, the notion of focusing on what’s really needed to live what its proponents call a ‘good life.’ The workshop reminded me again that festivals should prioritize quality over quantity, that it’s not about audience size and the number of artists or artworks in the show, but about creating experiences and making them meaningful. Rather than spaces for consuming culture, we should create spaces for transformation and connection.

One thing I’d like to see more of is communication between festivals and institutions. When an artist has to fly to Europe for a project, for example, it would make sense to coordinate other shows, meetings, and events to make those emissions count. For this to happen, however, the obsession with exclusivity in festival line-ups and cultural programs has to soften. We need cooperation, instead.

For festival workers, it’s hard to take in NEW NOW festival and not think about what the site, a former coal mine, and the post-industrial imaginaries on view mean for cultural production. There’s a direct connection between Zollverein’s fossil fuel legacy and the enormous footprint of the cultural sector. Festivals may be innovators but they’ve yet to address (or fully acknowledge) the true costs of international logistics and powering huge shows. The trends, it seems, all point in the wrong direction: shows get bigger, not smaller, and the growing appetite for immersive spectacles—look no further than London’s Outernet and the Las Vegas Sphere—begs some fundamental questions: What are the metrics for engaging audiences meaningfully? How can we best serve our communities? And what kind of precedents do we want to set for the future?

To find out, NEW NOW curators Jasmin Grimm and Rafael Dernbach invited Wiktoria Furrer and René Inderbitzin, two researchers from the Zurich Knowledge Center for Sustainable Development (ZKSD), to put festival makers and goers to the test. In an opening weekend workshop that comprised a series of self-reflection and visioning exercises, they encouraged this heterogeneous group of professionals and members of the public to unlearn growth-driven practices and rethink cultural production and consumption.

Workshop: “Patchwork Futures: The Challenges of Sufficiency” with Wiktoria Furrer & René Inderbitzin (Zurich Knowledge Center for Sustainable Development)

In their seminal 1972 report, The Limits to Growth, the international think tank the Club of Rome modelled the economic and population boom far into the 21st Century. The results don’t bode well: On a business-as-usual trajectory—the one we’re currently on—the model predicts overshoot and collapse before 2070. A more granular view into why offers another pivotal paper: In the ”Great Acceleration” graphs, German researchers demonstrate how the exponential rise of atmospheric CO2, methane, soil nitrogen, ocean acidification, and plastic pollution maps one-to-one on the growth of GDP.

There’s a mountain of evidence that economic growth drives the planetary emergency, ZKSD researchers Wiktoria Furrer and René Inderbitzin argue at the beginning of their workshop. We need to reorganize society and, yes, cultural production around eco-sufficiency, they say, because the dominant sustainability strategies, efficiency and consistency, simply aren’t enough. Efficiency improvements do help curb energy and resource use, but demand rebound effects cancel almost all sustainability gains. Over the past 50 years, for example, cars have gotten a lot more fuel-efficient but they’ve also gotten bigger and heavier, and their numbers grew tenfold. The promise that we can meet all our energy needs sustainably by switching to renewables—consistency—doesn’t hold up either: these technology transitions take time and are very resource-intensive.

“We hear more about efficiency and consistency strategies because they’re compatible with growth,” Furrer says of the neoliberal belief that we can mine and engineer our way out of the climate crisis. Eco-sufficiency, a concept first introduced by MIT professor Thomas Princen, promotes alternative models of wealth instead. Only when we prioritize immaterial riches like happiness and community, can the excesses of material consumption, particularly in the Global North, be curbed. That, of course, is easier said than done. “Growth has become such an important mental infrastructure, that it governs how we see and navigate the world,” Furrer says. “It’s incredibly difficult to get rid of.”

The cultural sector, too, is obsessed with growth, the participating festival makers were quick to admit. “Funders don’t care about the quality of the program or the difference your event makes for a community,” says Jeanne Charlotte Vogt, director of Frankfurt’s NODE Forum for Digital Art. “What matters, ultimately, are the stats: number of booked artists, audience size, press clippings, and social media reach. And after a while that gets into your head.” The pressure to perform goes far beyond a single festival edition. On the internet, festivals are in international competition with one another and incentivized to crank out content to feed the algorithm all year round. “We’re locked into FOMO infrastructures,” says NEW NOW’s Rafael Dernbach, “that keep us in a permanent state of stress.”

Festival workers are not the only ones exhausted by the relentless chase for relevancy and attention. “Artists have to deliver under this pressure and are forced to produce, produce, produce because festivals and institutions need their premieres,” says Jarl Schulp, director of Amsterdam’s FIBER festival. And the bigger the premiere, the better. Notoriously underpaid arts writers, then, complete the extractive content cycle, penning glowing reviews that organizations can take back to their funders. “Content, audience, traffic: everything has to be a number to be understood by the system,” groans Future Festivals project lead Maurice Jones. And the system depends on those numbers going up.

“Sufficiency comes from the word suffice—to be enough,” René Inderbitzin reminds participants as they head into the visioning sessions. But how much is ‘enough’ to sustain a festival? How many resources do organizations really need, and how should they be distributed internally and throughout their ecosystem?

Naomi Johnson, director of the Toronto-based Indigenous film and media arts festival imagineNATIVE, reminds the group that Indigenous communities have practiced sufficiency for millennia. “We open our festival with the ‘Dish With One Spoon’ wampum, an Indigenous treaty that recognizes everyone’s right to eat—and that you’ll never take more than you need,” she explains. It’s a set of values that runs counter to everything evangelized in Western societies. “We’re conditioned to not just take what we need today but more than we need in preparation for the future,” notes MUTEK founder Alain Mongeau. “Simply existing is difficult.”

To help participants hash out their needs and determine what should and shouldn’t grow, Furrer and Inderbitzin hand out templates for ‘sufficiency roadmaps’ to the year 2050. Split into five groups, participants assessed their current situation, internal and external obstacles, and charted future visions for anything from curation to communication.

The results they came back with echoed many of the challenges and dreams the Future Festivals group articulated early into the project. There was broad consensus, for example, that the grind, production excesses, and unhealthy reporting metrics have to end. We need to do away with platform dependencies and our obsession with exclusivity and novelty. Conversely, there’s infinite potential for things like equity and solidarity to grow. We need more access, accountability, and spaces for un-productivity, participants agreed.

But where to begin with the transformation? Ideally early on, Maurice Jones suggests, by reforming education. The privatization of academia, for example, turns universities into workforce production spaces, with little room to experiment and explore alternate ways of thinking and doing. “We need to improve the research experience, where we can embrace the process without the pressure to publish.” More responsible modes of publishing would also help knowledge production, Jones argues. “Researchers could collaborate on fewer but better papers rather than adding to the noise.”

More responsibility is also required in how we use social media. Rather than broadcasting to everyone and around the clock, we could cultivate bespoke and more direct communications and make sure we keep offline audiences in mind, Jeanne Charlotte Vogt suggests. We definitely need to regain control from our algorithmic overlords. For that, we need healthier networks and that might mean boycotting toxic platforms altogether. As HOLO guest editor Nora N. Khan tweeted in support of the WGA writers strike in May 2023, “There is enough content from the last year for the next century.” Khan’s workers rights advocacy also makes a great case for sufficiency.

Everyone agrees that a lot can be achieved with more collaboration—across fields, organizations, and communities. Sharing knowledge and resources may seem an obvious way to reduce emissions and build resilience, but a lot of organizations work in isolation. “It’s important to realize that you’re not alone in what you’re doing,” Alain Mongeau urges fellow cultural workers. “Find your peers and connect with them!”

Early on in the workshop, the festival makers and cultural workers in attendance self-identified as mediators, translators, navigators, and narrators who build bridges between communities, bring stakeholders together, and create access to critical knowledge. Who could be more important for putting society on a path to sustainability? If the predictions made by the Club of Rome are right—and a 2014 expert reassessment suggests they are—we’re headed for degrowth of some kind. It is up to us, the people shaping culture, whether it will take the form of collapse or reformation.

Wiktoria Furrer and René Inderbitzin are sustainability researchers and educators at the Zurich Knowledge Center for Sustainable Development (ZKSD). Furrer (who since joined the FHNW School of Education as Chair of Art and Theater Education) studied political science and cultural media studies, and holds a PhD in cultural analysis. Inderbitzin holds a bachelor’s in natural resource science and a master’s in sustainability science.

Sufficiency addresses these shortcomings by advocating for an overall reduction of our energy and resource use. As a strategy, it is quite straightforward: sufficiency means that we consume according to our needs, not wants, and live what researchers Uwe Schneidewind and Angelika Zahrnt call “the good life” within the limits of the eco-sphere. In addition to reducing consumption, sufficiency encourages the transition to a sharing economy with a strong emphasis on repair and reuse. This involves ‘unlearning’ neoliberal beliefs rooted in the myth of infinite growth, the creation of new social practices, and the adoption of new role models. To maintain our quality of life and improve our overall well-being, we need to prioritize non-material wealth, like happiness or time spent with friends and family.

It’s worth noting that the implementation of eco-sufficiency strategies is particularly important in the Global North. It’s here where, today and historically, the majority of resources are being consumed, while people in the Global South face the brunt of the consequences.

Q: Between the ideological grip of neoliberalism and Western culture that celebrates consumption—what, in your experience, is the biggest hurdle to sufficiency?

A: The primary problem is an economic system that relies on infinite growth. It’s a belief system that permeates society and prevents us from making the big structural changes necessary for bringing human civilization and the planet back into balance. On an individual level, we found that the main hurdle to reducing one’s footprint is not a lack of knowledge or motivation but a lack of time, which in itself is a result of extractive labour practices.

Access and Inclusivity

When it comes to discussing the future of festivals, there are few cities more appropriate to host that conversation than Montréal. A city that lives and breathes art and performance, Montréal is home to renowned cultural producers; Cirque du Soleil made the circus arts into a billion-dollar industry, Just for Laughs is a fabled testing ground for up-and-coming comedians, and MUTEK is one of the most revered electronic music festivals on the planet. Nowhere is this more evident than Esplanade Tranquille, where for a week each August, Quartier des spectacles—a public square right in the middle of downtown Montréal—transforms into a packed dancefloor.

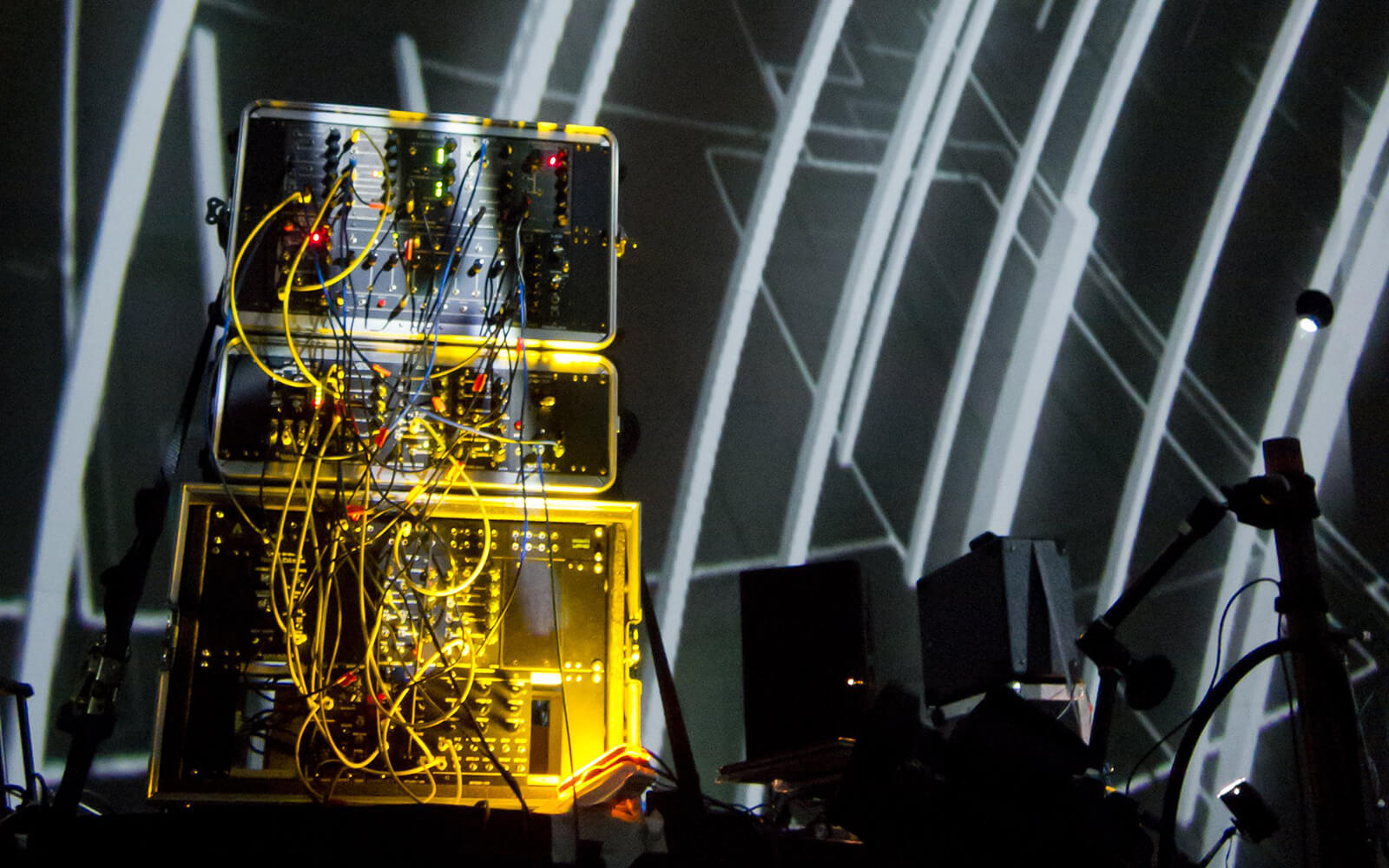

Founded in 2000, MUTEK was launched to celebrate the music-technology avant-garde. Unlike any other festival or club night in North America at the time, in scale or ambition, it brought global figures to Quebec and put Canadian electronic musicians onstage beside them. Coil, Monolake, Matmos, and Plastikman graced its early stages, linking acts featured by Europe’s most progressive clubs and esteemed record labels with the sounds bubbling up from the Canadian underground. Notably, MUTEK programmers pushed back against the (then) larger-than-life figure of the DJ and instead centred live electronic music. Laptops running early versions of Ableton Live, vintage synthesizers and drum machines—MUTEK didn’t just bring the studio onstage, it made it the life of the party.

MUTEK quickly established itself as an oasis for North American electronic music fans and attracted globetrotting ‘techno tourists’ from Europe, South America, and Asia. Right from the start, it was a place where analog rhythms and digital glitch soundscapes were mirrored by inventive and audacious scenography. Collaborations between musicians and visual artists were so fruitful that A/Visions, a dedicated program for audiovisual experimentation debuted in 2007, cultivating more cinematic and gallery-like contexts for enjoying electronic music. In 2013, the MUTEK team saw the opportunity to showcase more of the experimentation and innovation going on in the digital art and creative industries (and VR quite specifically) that didn’t fit within the existing festival parameters: MUTEK_IMG, a symposium that later became the MUTEK Forum was born. As the festival expanded in scope and reach, spawning global satellite editions in Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Tokyo, and Santiago, the key questions driving MUTEK forward remained the same: What exciting forms can electronic music take? What are the critical aesthetics of emerging technology? And how can the digital arts intersect with broader societal concerns (and wider audiences)?

During the 24th edition of MUTEK’s flagship Montréal edition, these questions were asked around the clock. By night, Tim Hecker blasted haunting soundscapes while enveloped in a cloud of fog, Hatis Noit’s searing vocals melded into uncanny AI imagery, and an all-star cast of dancefloor-focused artists including AUX88, Jennifer Cardini, μ-Ziq kept thousands moving till dawn. By day, MUTEK Forum served up discourse: AI Now Institute’s Sarah Meyers West lobbied for Big Tech regulation and accountability as the only sane response to the explosion of large language models, Winslow Porter shared insights gleaned from a decade of trailblazing immersive VR filmmaking, and Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson opened up about the struggles of running Dweller—New York’s first electronic music festival exclusively focused on supporting and celebrating Black artists. The roster of international artists and thought leaders shared the stage with local talent and industries: represented were Montréal’s burgeoning XR, animation, and videogame producers; students and educators from Concordia University and UQAM; and cultural producers from local galleries and institutions, the DIY scene, and activist communities.

Beyond showcasing the bleeding edge of postdigital aesthetics and discourse, MUTEK tasked itself with some extra-difficult homework as the instigator of the Future Festivals project: part of the forum was carved out to discuss where cultural producers were struggling and falling short. The resulting dialogues were bleak at times but also hopeful. MUTEK has long been aware of its role as a cultural leader, but still, despite initiatives to increase access—a pledge to work towards lineups of 50% female-identifying artists, an overhauled accessibility policy produced in consultation with the Crip Rave collective—these conversations underscored just how much work remains to be done.

Focus: Electronic music, audiovisual performance, digital art

Location: Montréal / Tiohtiá:ke / Mooniyang, Quebec, Canada

Launch: 2000

Frequency: Annual (end of August)

Visitors: ~66,500 (in 2023)

Team: 9 permanent staff

Structure: NPO (nonprofit organization)

Funding: Public (national, provincial, municipal)

Satellites: Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Santiago, Tokyo

Formats: 6 days, 24 events in 6 venues; large-scale audiovisual performances, immersive exhibitions, electronic music showcases, conferences, professional activities

Alain Mongeau is the founding director of MUTEK Montréal, North America’s premiere festival for exploring the intersection between electronic music, sound research, and digital creativity. Previously, he directed the new media division of the Festival of New Cinema (1997-2002) and was the director of the sixth International Symposium of Electronic Arts, ISEA95 (1995). Mongeau has a PhD in Communications and lectured on computer-based communications at the University of Quebec (1990-93).

In 1997, I joined the Montréal Festival of New Cinema (FNC), where I directed the new media wing for five years, until 2001, during which the event was renamed the Montréal International Festival of New Cinema and New Media (FCMM). My mandate was to develop a new media program in relation to moving images. But at that time, no one really knew what that meant. My strategy was to create an environment inspired by Hakim Bey’s 1991 book The Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ), in which he describes TAZs that elude formal structures of control. At the festival, visitors could immerse themselves in the digital culture of the moment, with a strong presence of electronic music. I believed the evolution of sound technology foreshadowed what would happen with the moving image since the latter is more demanding in terms of computing power. This gave rise to FCMM’s famous Media Lounge, which notably saw the first manifestations of VJing in Montréal. During my years there, the FCMM had three components—full-length films, video and short films, and new media—which coexisted somewhat awkwardly as three parallel realities, each with their own different logics. In the end, it was more like three festivals in one, that offered richness, but also required compromise, a sense of cohabitation, and mutual understanding. In 1999, when the offices of the FCMM moved to the newly completed Ex-Centris complex imagined by patron Daniel Langlois, I inherited the mandate to develop new media more broadly. MUTEK was born within this context, conceived as the flipside of what I was doing at the FCMM. Rather than exploring new media in relation to the moving image, I focused on sound. MUTEK’s subtitle at that time: ‘Music, Sound, and New Technologies.’

For two years, in 2000 and 2001, MUTEK and the Media Lounge of the FCMM alternated every six months to cover each pole of the new media territory. The shock of September 11th, however, took its toll on the Media Lounge—people were not in the mood for cultural outings a few weeks after the attacks and that year’s FCMM edition ran a significant deficit. The first recovery measure was to abolish the very expensive new media section—and revert to the previous name of FNC. MUTEK, on the other hand, gradually weaned itself from Ex-Centris to fly on its own and cover digital creation more broadly. Eventually, MUTEK’s subtitle became ‘Digital Creativity and Electronic Music.’ In retrospect, MUTEK can boast about being the first event purely native to the digital realm in Montréal—without constraints or compromises.

A pivotal but lesser-known factor that helped MUTEK’s global expansion was my involvement as the program chair of ISEA95, the 1995 International Symposium for Electronic Arts in Montréal. The resounding success of the edition led to the relocation of the ISEA headquarters to Montréal in 1996, where I assumed leadership until 2000. This period exposed me to the intricacies of managing an international organization, complete with internal politics and tensions. During my tenure, the ISEA symposium took place in Rotterdam, Chicago, Liverpool/Manchester, and Paris, offering invaluable insights into navigating the complexities of the cultural sector in different countries. With MUTEK, I was able to apply my new skills of diplomacy in action, in a context where everything was still to be done—in uncharted territory.

For MUTEK’s 20th anniversary in 2019, we strategically aligned the Forum with the festival dates, officially designating the Forum as MUTEK’s de facto daytime component. The Forum follows its own programming logic, enjoying the freedom to explore a spectrum of topics—from technological innovations to social impacts and environmental sustainability. It functions as a radar, scanning new issues, emerging trends, and uncharted territories. Over time, we believe that the forum will progressively shape the festival, or conversely, the festival will adapt to intersect with the issues addressed by the forum. And as the two resonate more and more, the boundaries between the different audiences blur.

Q: Compared to other regions in North America, Montréal’s home province of Quebec is well-known for its generous arts funding, providing for a plethora of festivals in the city. Why do you think it is that culture is valued so much here compared to other cities? What municipal initiatives or policies do you find particularly helpful and worth emulating, and where do you think the city’s support structure has room for improvement?

Culture in Quebec has consistently served as a crucial element of resistance against the looming threat of assimilation. The province of Quebec is a small island of 8 million French-speaking people, amidst a sea of over 350 million (predominantly) English speakers. Canada has protectionist tendencies in response to the influence of American culture; to uphold and support national culture was a sheer necessity. All three levels of government—federal, provincial, and municipal—end up supporting culture, each to a different extent. In this regard, we are quite privileged compared to many other countries, so it’s hard to complain. Nonetheless, there is always room for improvement and more support, particularly for small and mid-size festivals like MUTEK.

The relationship with the local and national creative community is one of the fundamental reasons for the existence of a festival like MUTEK. It’s similar to how the blood that circulates in our veins and keeps our system alive—a connection that defines and shapes our identity. This explains why, when MUTEK is invited to curate an event abroad, we strive to include Canadian artists. Similarly, when an international chapter of MUTEK establishes itself in another country, we ensure that the organizers are interested in developing and nurturing a connection with their immediate community.

The pandemic illustrated the resilience of our international network quite effectively, I think. In Montréal, for instance, we made various efforts to present hybrid versions—both in-person and virtual—of the festival, providing a platform for artists to stay active by exposing them to audiences here and abroad. The other branches of MUTEK abroad did the same, in a gesture of mutual solidarity that strengthened the concept of a global creative community.

The idea of doing MUTEK festivals abroad wasn’t part of our initial plans; it unfolded organically. The first one happened in Chile in early 2003. After we hosted Ricardo Villalobos and Martin Schopf (Dandy Jack) with their Ric y Martin project at MUTEK 2001, Martin thought Chile could use a festival like MUTEK. And when I visited the country at the end of that year, he introduced me to Pol Taylor, who’d already done a few memorable events—the seed was planted. Mexico came second and was as unexpected. In the fall of 2003, Quebec was the guest of honour at the Guadalajara International Book Fair. MUTEK took part in the cultural activities surrounding this event by organizing a micro MUTEK festival tour of three cities: Tijuana, Guadalajara, and Mexico City. MUTEK has remained in Mexico City ever since!

An entire chapter could be written about the circumstances that brought us to different regions of the world. But when I zoom out, there’s a big picture that forms. The philosophy behind nurturing a network of somewhat independent MUTEK branches lies in the belief that electronic music is a universal language capable of bridging differences between regions and cultures—in a sense, electronic music is the soundtrack of globalization.

Each branch celebrates that ‘universal language’ with a certain degree of autonomy that allows it to adapt the MUTEK ethos to its local context. By doing so, we foster diversity within a shared framework. Navigating the disparate realities each node faces on the ground has taught us the importance of flexibility, cultural sensitivity, and collaborative engagement. Recognizing and respecting the unique challenges, opportunities, and artistic expressions in each location is crucial. It requires a balance between providing a consistent global identity for MUTEK and allowing enough space for local interpretation and innovation. Learning from the varied experiences of each node enriches the overall network, cultivating a dynamic exchange of ideas, talent, and cultural perspectives. Ultimately, the MUTEK network operates as a big family, with all the ups and downs. I think it’s quite unique.

With tens of thousands of annual visitors—66,500 in 2023, to be precise—MUTEK is a magnet not only for art and music lovers but for global festival makers and cultural workers. It’s where industry people gather to discover new talent, to vibe-check, and to gossip about the scene. Capitalizing on this expert presence, Future Festivals project instigator Maurice Jones and MUTEK Forum Creative Director Sarah Mackenzie integrated a range of activities—Future Festivals Labs—into the program. In a variety of discursive formats, festival makers were encouraged to be vulnerable in public and have earnest conversations that are seldom heard by audiences. Rather than talk about reach and celebrate programming highlights, representatives from Dweller, imagineNATIVE, NEW NOW, and other festivals revealed what they are struggling with and where things need to change. On August 22nd, the first day of the Forum, a keynote and panel discussion tackled a wide range of concerns—from ethics and equity to the perennial funding anxiety to existential doubts about how much the arts are valued by the wider public.

Keynote: “Festivals as Radical Rituals” with Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson (Dweller)

Panel: “Forging New Horizons” with Maurice Jones (MUTEK), David Lavoie (Festival TransAmériques), Jasmin Grimm (NEW NOW), Naomi Johnson (imagineNATIVE)

House and techno were created in Black communities—but you wouldn’t know it by looking at international club circuit where lineups of straight white cisgender men abound. “Black artists are so rarely centred in electronic music spaces,” says Frankie Decaiza Hutchinson in her MUTEK Forum keynote, “Festivals as Radical Rituals,” of the representation lapse that inspired Dweller, an electronic music festival she founded. Following Discwoman, her pioneering (and now defunct) booking agency for women and non-binary electronic musicians, Hutchinson programmed a night of house and techno at Brooklyn’s Bossanova to celebrate Black History Month in 2019. “Booking a festival with exclusively Black artists makes what is going on in the broader industry glaringly obvious,” says Hutchinson.

Correcting a gap in representation creates community. Dweller’s multi-generational alumnae (including Juliana Huxtable, Jeff Mills, and Dreamcrusher) has grown and there is now so much interest that Hutchinson wonders “how can we accommodate the growing number of Black artists that want to play?” Beyond programming, festivals have other ways to engage their audience, as evidenced by Dweller blog editor Ryan Clarke, who used the pandemic live music pause to curate a deep archive of articles (and mixes) that provide critical perspectives on Black electronic music; recently, it has been expanded into a resource on Afro-Palestinian solidarity.

Pushing back against the status quo inevitably garners backlash. “I have a very bleak view of this industry,” says Hutchinson in a moment of unvarnished honesty about her opinion of unnamed international promoters. When asked by a woman of colour how musicians could make their way without being permanently enraged Hutchinson’s advice was that “artists should not feel too bad for doing what they have to to survive.” It’s up to cultural producers to make ecosystems more inclusive so future generations of artists won’t have to make (as many) concessions when considering potential bookings.

Every industry was turned upside-down by the pandemic but the impact within the cultural sector was jarring and profound. Beyond the fact programming and budgets were upended and multi-year projects cancelled or downsized overnight the pressure on the (already over-taxed) staff was immense. “I didn’t have the luxury of a pandemic career change: I had to hold shit together,” says Naomi Johnson early in the panel discussion of the struggle to shepherd Toronto’s imagineNATIVE through the last few years. Fellow festival makers David Lavoie (Festival TransAmériques) and Jasmin Grimm (NEW NOW) shared similar stories of frustration and resilience, with the latter wondering “how do you take the knowledge gleaned from the last three years into the future?”

Ironically, the present may be more challenging than 2020-21 was. At least there were support programs for arts organizations when the economy ground to a halt. “Now that the pandemic is over we’re left with funding cuts,” notes MUTEK’s Maurice Jones. The resulting austerity coupled with inflation and rising prices of flights and hotel rooms have severely hamstrung programming budgets. Lavoie was so concerned about the storm clouds he saw gathering, that he and other cultural producers wrote an open letter to the citizens of Montreal in February 2023 warning that “our ability to provide meaningful programming and to contribute to the job market and the economy is at risk.” Some festivals will be nimble enough to survive but “sometimes organizations have to die,” he notes glibly.

In addition to questions of capacity and funding, another major issue is how opaque the cultural sector is to non-insiders. “We’re really bad at advocating for ourselves” Jones observes, about how festival teams are generally too busy to worry about if—beyond attendees—the general public understands the value being created. The inscrutability of dance and theatre, Indigenous-made media, and digital art and electronic music to the wider public is a challenge to overcome. “Art has been systemically eliminated from every corner of the public sphere. We’re now seeing generations of people with no understanding of how the arts might fit into their lives,” warns Johnson.

While the economics are grim, necessity is the mother of invention. If, after decades of reliable funding, festivals and the arts have to make their case to the public about how they create jobs, stimulate the economy, and enrich lives—so be it.

Crip Rave is a Toronto-based collective, event platform, and consulting hub showcasing and prioritizing Crip, Disabled, Deaf, Mad and Sick body-minds within safer and more accessible rave spaces. It was co-founded by Mad and Crip organizers Renee Dumaresque and Stefana Fratila, who draw on lineages of Disability Justice and Crip community wisdom in their work.

The feedback from the Crip, Mad, Sick, Deaf and Disabled community has been overwhelmingly positive. It’s also been really exciting to hear from people who don’t identify as disabled about how much better their experience has also been with attention to accessibility—most people want access to free water, a place to sit and a room to decompress. Our hope is for all people—regardless of disability-identity or experience—to recognize their own personal stake in enhancing accessibility within Rave and electronic music culture. Prioritizing accessibility for Crip, Mad, Sick, Deaf, and Disabled people makes an event more accessible for everyone.

Q: The DJ booth is a heavily coded space. Tremendous meaning is derived from the musical gestures that emanate from it and many unspoken rules dictate who gets to be in it. It’s a site you put under the microscope in a 2021 workshop facilitated by Syrus Marcus Ware. Could you tell us a bit about how that went and walk us through what a more accessible and equitable version of the DJ booth looks like?

A: The workshop that Syrus Marcus Ware facilitated was called “Cripping the DJ Booth.” In terms of language, we use words like Crip and Mad because they are politicized terms that have been reclaimed by a range of communities around disability, mental health, chronic pain and illness, etc. These words are often taken up as an identity but our objective is to enhance the conditions of work and play for anyone with related lived experiences, regardless of what language they use or identify with (if any). Crip also gestures to a political and artistic orientation or a praxis that exposes and counters the ways that ableism, sanism, and audism, for example, shape the norms that guide non-disabled spaces. By approaching ‘the DJ booth’ from a Crip politic, Syrus invited attendees to learn and engage with technology in a way that works for—instead of asking us to override—the body and mind. He emphasized building a track list with time for a bathroom break in mind to working with the multi-sensory nature of sound through the visual act of DJing, and the importance of bass and vibrations for Deaf folks. He also advocated for threading activist and abolitionist archives into your set and DJing with attention to economic justice, because, and these are his words, “crips are often under-resourced—over-talented and under-resourced.”

A large part of our work is challenging the narrow and limiting understandings of disability by emphasizing that Mad and Crip DJs and producers are already in the room, while simultaneously addressing the industry and societal norms that have pushed people out or made it impossible for them to be there in the first place.

We always encourage festivals and events to start wherever they are. Crip organizing shows us the value in slow and sustainable work rather than operating from a place of urgency and scarcity.

Q: Bigger festivals, clubs, and more underground DIY communities have varying relationships with capitalism. What differences do you see across this spectrum of more commercial to less commercial event organizing, in terms of how they are responding to disability advocacy? Where is the most progress being made?

A: There’s certainly a wide spectrum, but the most progress is undoubtedly being made in DIY and underground spaces that are value-driven and have the fewest resources. There has been huge work around the creation of safer spaces and collectives prioritizing underrepresented talent, which contributes to accessibility in both direct and indirect ways, and more and more, we are seeing a broader interest across the spectrum from promotors and festivals wanting to learn and make changes that address barriers for disabled communities in particular.

Engaging this work with attention to economic justice means both challenging the impulse of capitalism to profit above all else, while also acknowledging that under capitalism people need to make money to survive. Most organizers need to make concessions and we want this work to be sustainable while asking ourselves hard questions about the values, assumptions, and norms that shape or define what we understand as non-negotiable and who is commonly excluded from the decision-making as an effect. We’re really excited by festivals and parties doing what they can with what they have. Sharing event accessibility information is a great place to start—even sharing the aspects of your event that are likely inaccessible for many people still works in service of generating greater accessibility.

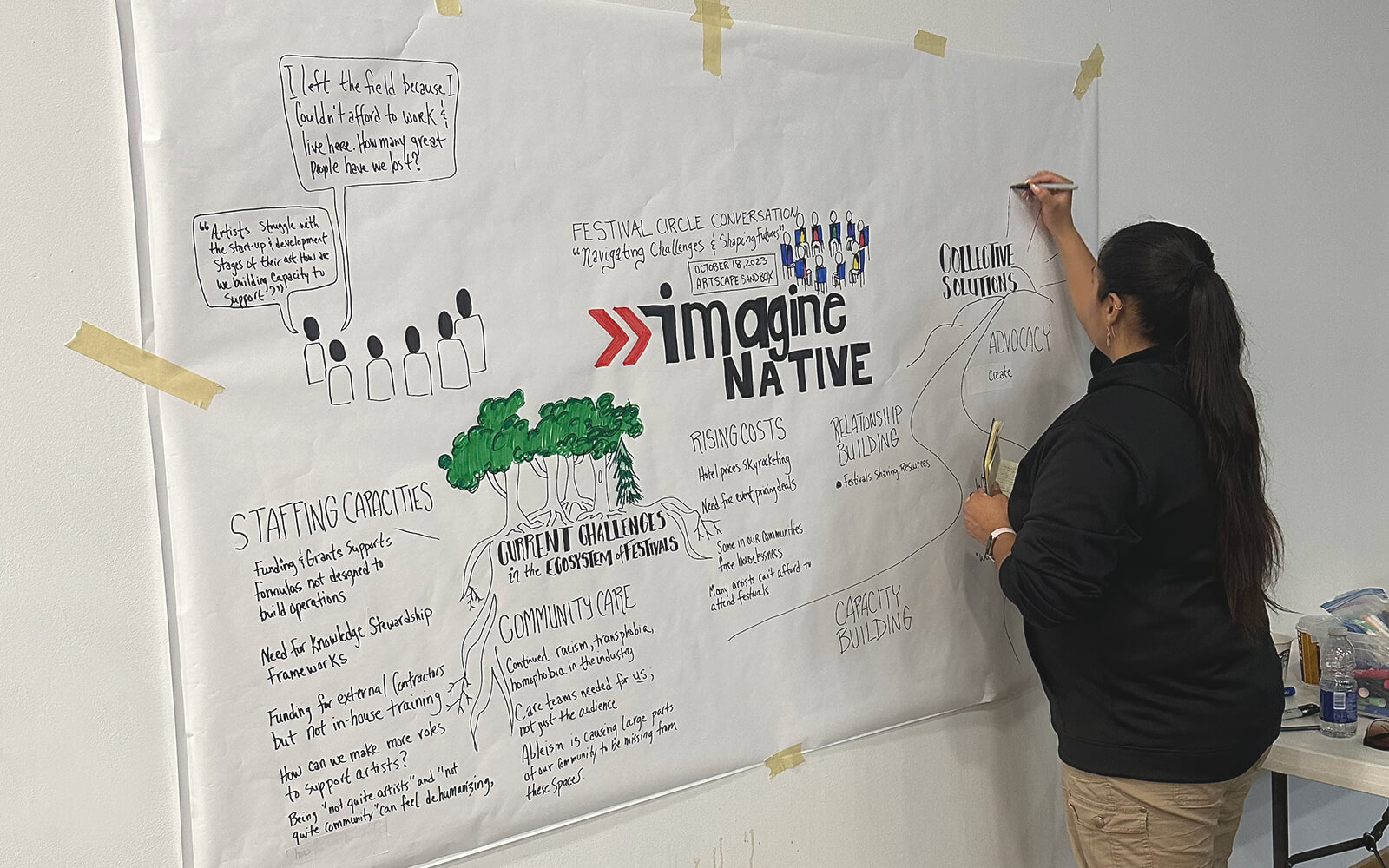

Give festival makers the stage to discuss the state of cultural production and conversations will likely center on economics. Too many organizations operate at the edge of precarity that just staying afloat becomes the primary concern. Put about 100 stakeholders—festival organizers, arts workers, emerging and mid-career artists, students and activists—in a room and the full range of persisting problems comes to light.

On August 24th, the MUTEK Forum invited voices from inside and outside of the Future Festivals project to share both challenges and successes in an open roundtable format as a way to spark a conversation with the community. Emerging BIPOC artists and vulnerable groups used that opportunity to—rightfully—demand more access and accountability.

Roundtable: “(Jointly) Expanding Orbits of Future Festivals” with Kaitlyn Davies (Refraction), Marie Pier Gauthier (National Film Board of Canada), Damian Romero (MUTEK.MX), Cam Scott (Send+Receive), Kris Voveris (New Forms)

Unlike the Future Festivals panel discussion on August 22nd, where festival producers grumbled about similar problems, the roundtable highlighted the wildly different realities within the cultural sector. Drawing on notions of scarcity and abundance, the case studies presented made clear that varying levels of gentrification and the divergence in access to public funding create unique challenges (and opportunities) for festival producers across North America.

“We have a kind of Robin Hood intention with our core funding. We give it to artists, we try to make something happen for communities, and it’s easier for us to do without selling tickets,” says Cam Scott of Send+Receive’s shift to a pay-what-you-can model. That policy allowed residents of the Winnipeg neighbourhoods the sound art and experimental music festival takes place in to go hear artists like Speaker Music and Wok the Rock risk-free. That benevolence worked in Canada, a country where public funding ensures a baseline operations budget, but it’s not an option in Mexico. “We redesigned our entire business plan to make every program within our festival self-sufficient from its own sales. It was like getting back to our roots,” says Damian Romero about how MUTEK.MX rethought everything—funding sources, staffing, institutional partnerships, reengineering the financial viability of each part of the program—after the pandemic; and they emerged from that process reinvigorated and ready to charge into their third decade.

In Vancouver, counting every ticket sale is eclipsed by a more pressing issue: space. “They explained that they’re not interested in events with loud music that serve alcohol and prefer ones with a more corporate and technology focus. We basically got booted for a VR and AR conference,” says Kris Voveris of losing a key venue just before the 2019 edition of New Forms. The lack of affordable live music venues in Vancouver has proven so challenging that New Forms has had to manually adapt temporary spaces to serve their needs. These issues of appropriate contexts for presentation resonate in other corners of cultural production. “Is it viable? What’s the objective of presenting a project in front of a particular audience?,” says National Film Board of Canada (NFB) producer Marie Pier Gauthier about the introspection the NFB interactive team does every time they are invited to present one of their works. Varying audiences, varying budgets, and evolving tech make each staging a challenge—and the labour of (re)presenting the same projects in different ways at different festivals adds up.

Challenging traditional models of curating in her work with the Friends with Benefits (FWB) and Refraction Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), Kaitlyn Davies sees life beyond gatekeeping. “We think of FWB Fest as a container for other people to fill. We build the rails and have the infrastructure, we bring the generators and ice machines, and we rent the venue,” she says. The community shapes the programming and the artist selection process is transparent, thanks to online tools like Airtable forms and Figma boards, to “incite more collaboration.”

Kaitlyn Davies’ concerns about gatekeeping seemed to anticipate the feedback the panel received in the following discussion with the audience. Rightly concerned about the lack of support for emerging queer and BIPOC artists by established festivals, several young artists condemned the lack of governance and curatorial transparency in the arts and the limited opportunities available to them. “What are your success stories in terms of preserving the dignity of marginalized people?” asked one questioner pointedly. The conversation lingered on how the most vulnerable populations—newcomers, the disabled, transfolk—remain underserved by current diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. “You cannot treat marginalized people like consultancies to improve the image of an organization. We want to remove barriers that reproduce those markers when we invite people into our community,“ Scott responded.

Another questioner suggested the speakers weren’t thinking big enough when they talked about access. Beyond serving their immediate cities and countries festivals could make an impact overseas, she argued. “For me, the idea of access can be expanded beyond borders. If I can send a link, a file, a video, anything to a friend back home in Iran—that means something. So I’m curious what is preventing festivals from taking these kinds of steps?” Some festivals are better than others in archiving and circulating programming through platforms like Instagram, SoundCloud, or YouTube but the provocation forced a bold realization: ‘access’ also means solidarity and international sharing.

The divide between what was presented and how it was responded to was stark. A key takeaway is that while festival makers might have a long list of areas they are working on—the most pressing ones for artists and festival goers are clearly access and equity.

Narrative Sovereignty

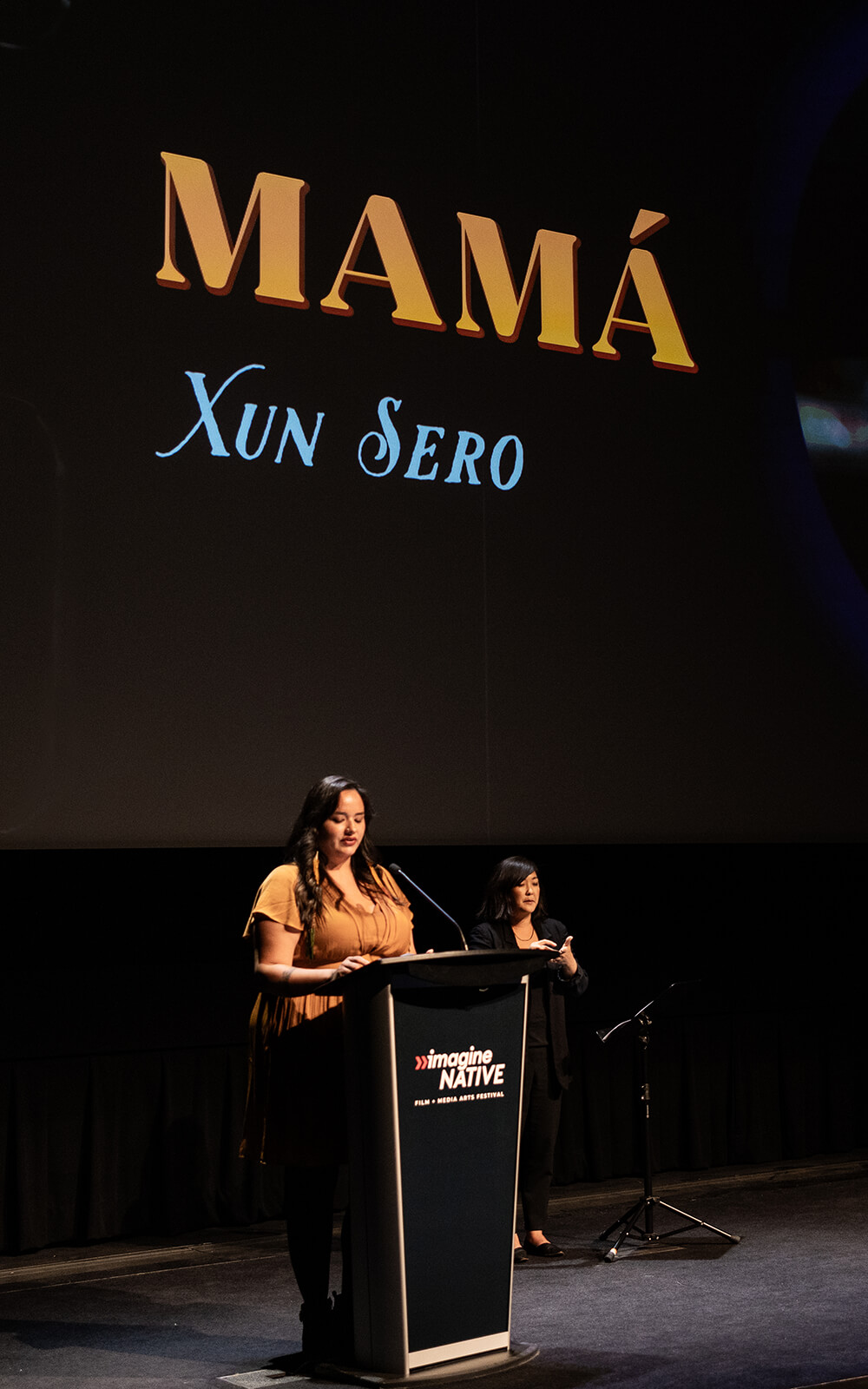

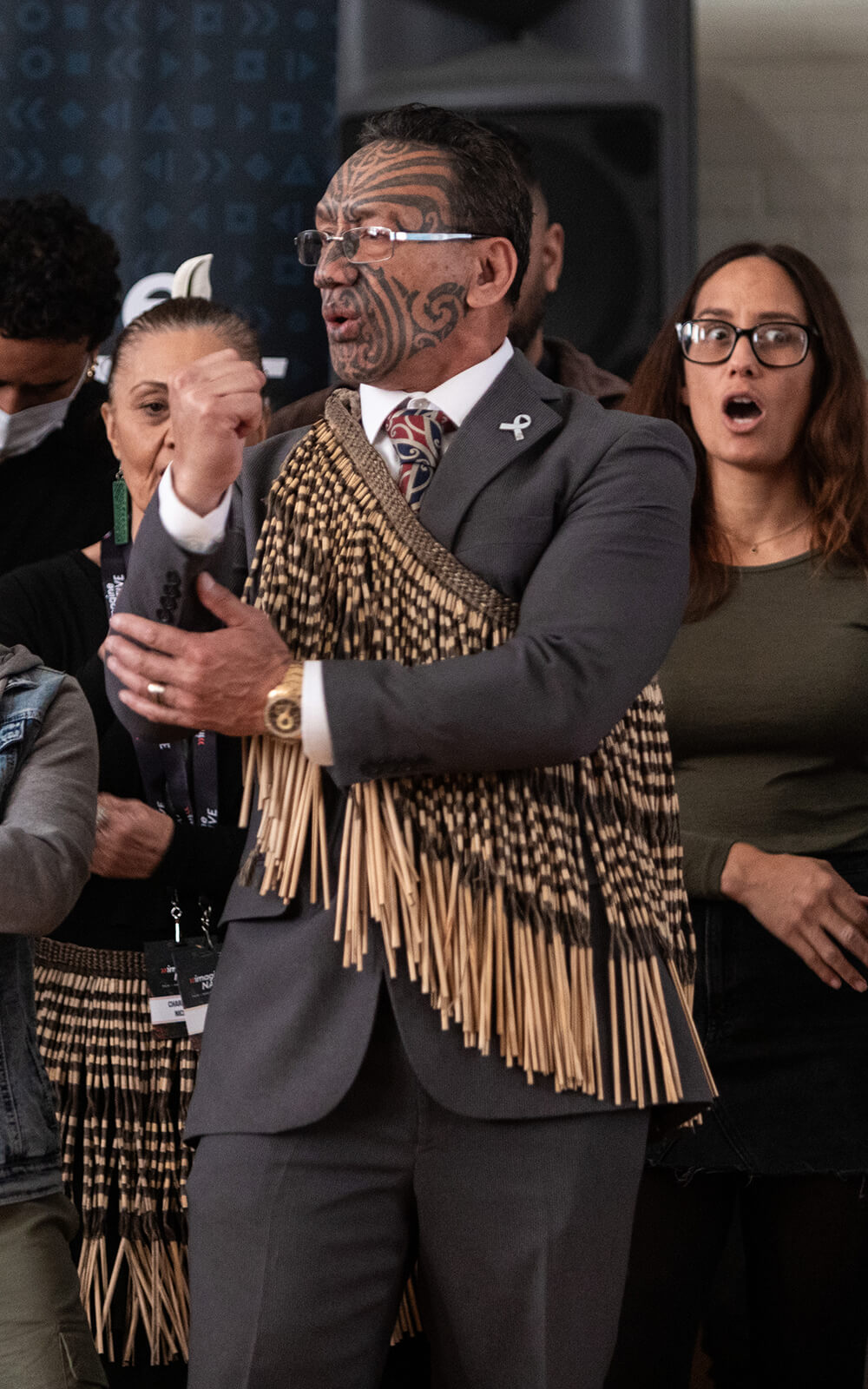

Occupying about a sixth of a downtown Toronto city block, the TIFF Lightbox is one of only a handful of cinema complexes in the world purpose-built for hosting an international film festival. But from October 17-22, 2023, its five cinemas, gallery, and restaurant were not swarming with the Hollywood-Cannes glitterati that frequent the Toronto International Film Festival, the venue instead bustled with hundreds of Indigenous screenplay writers, directors, and artists, all gathered for the 24th edition of imagineNATIVE. The world’s largest Indigenous film and media arts festival, imagineNATIVE celebrates Indigenous-made media across traditional screen-based formats (features, shorts, web series) through emerging interactive mediums (installation, videogames, VR).

Founded in 2000 by Cynthia Lickers-Sage and Canadian video art distribution hub Vtape, imagineNATIVE started to solve a daunting problem: there was nowhere for Indigenous filmmakers and video artists to show their work. In its early days “imagineNATIVE was the only option available—but it’s a different landscape now,” says Executive Director Naomi Johnson, contrasting the festival’s “scrappy roots” to a more amenable present moment when major film and television studios are finally receptive to Indigenous perspectives. Case in point: a show like Reservation Dogs, Sterlin Harjo and Taika Waititi’s critically acclaimed series about Indigenous teens in Oklahoma—made by an almost entirely Indigenous cast and crew—would likely never have made it to air on America’s FX network a decade ago. Once an upstart bent on fixing a representation gap in a national context, imagineNATIVE matured into a preeminent global meeting place for Indigenous media makers and (like Sundance or Hot Docs) a place for the industry to scout exciting new voices.

Programming highlights of the 2023 edition included the World and North American premieres of Fancy Dance (2023) and Odisea Amazónica (2021). In the former, Seneca-Cayuga director Erica Tremblay chronicles a girl’s coming-of-age search for her sister, exploring the impact of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis within a small community; in the latter, sibling Quecha directors Diego and Álvaro Sarmiento document the labour (and lives) that move goods up and down the Peruvian portion of the Amazon River. Also featured: a joyous binge-watch of episodes from the most recent season of the aforementioned Reservation Dogs with director and showrunner Sterlin Harjo. In all, 14 feature films and 70 shorts were screened. Beyond the moving image, the iNdigital Space was alive with interactive pieces from artists including Ojibwe inventor Danielle Boyer’s SkoBots (2022), which harnesses friendly robots in the name of Indigenous language reclamation, and Dene artist Casey Koyczan’s speculative VR experience EłeghààŁ ; All At Once (2022), which imagines a future North where huge animals roam. Additional new media works were displayed at satellite Toronto venues including InterAccess, Trinity Square Video, and Vtape.

An industry track showcased the imagineNATIVE Institute’s mentorship initiatives, with early-career Indigenous filmmakers, musicians, writers, and story editors sharing their experiences developing a short or completing a screenplay; a full-on pipeline, much of the material nurtured in these programs will be screened in the imagineNATIVE Originals track in future editions of the festival. Most festivals incubate content and support creators, but here the focus is not only on helping Indigenous creators find (and preserve) their voice but setting them up to navigate a not-always-so-benign industry with a network of support to draw on. Beyond the lucky few who receive direct mentorship, a robust and generous awards program (with a total of $65,000 CAD in prizes) recognizes and nurtures talent across mediums and formats. “We will manage our own destiny and maintain our pride and identity through story,” reads the mission statement in the program. This mandate to assert Indigenous narrative sovereignty and a culture of care is infused through every imagineNATIVE initiative.

Unsurprisingly, care and support provided the framework for the third Future Festivals Lab. Rather than keynotes, panels, or roundtables in the public eye, imagineNATIVE hosted a ‘culture workers only’ private sharing circle. The mix of global Indigenous curators and culture workers and local festival makers and event organizers communed to ask big questions: How can culture workers care for themselves and grow while doing their important work? What do deeper and more meaningful collaborations look like? And how might cultural organizations remain fluid and meet the needs of their local communities?

Focus: Indigenous cinema and video, media and digital art

Location: Tkaronto / Toronto, Canada

Launch: 2000

Frequency: Annual

Visitors: ~23,500 on-site, 7,000 online

Team: 16 permanent staff

Structure: NPO (nonprofit organization)

Funding: Public (national, provincial, municipal)

Formats: Screenings, exhibitions, performances, conference, supplementary online and national tour program

Naomi Johnson, Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Bear clan from Six Nations, is Executive Director for imagineNATIVE, the world’s largest Indigenous film and media arts festival. She previously served as the Artistic Director at the Woodland Cultural Centre for seven years. In 2023, Naomi received the Margo Bindhardt and Rita Davies Award from the Toronto Arts Foundation for arts and culture leadership.

It’s fabulous that there are way more opportunities now, but I think what makes us special is how we provide opportunities. We are a very relationship-driven organization. Relationships matter to us. I think it’s central to our mission to ensure creators feel supported and provided with a safe place to come to. Trust is top of mind for us with all the work we do, even with big partners. If we’re dealing with a gaming company or a distributor we make sure that the relationship is good and that the people we are dealing with have the same values as us. There have been many times when a relationship has gone sour, and I’m left thinking ‘I did not like what they said’ or one of my team members says ‘I did not like how they talked to me’ in a meeting. If the vibe is off we sever the relationship.

There’s more and more support available though. The Indigenous Screen Office, which was recently formed, can provide great funding opportunities for filmmakers who have established themselves and have several projects under their belts. We complement this by being a platform for everyone. It doesn’t matter what level of your career you’re at—we want you at imagineNATIVE.

I directly benefitted from imagineNATIVE’s approach to mentorship when I trained for a whole year under my predecessor Jason Ryle before assuming the Executive Director role. That was a really good indicator of what kind of organization this is. Currently, the role of Associate Director has been reinstated with my colleague, David Morrison in this position. A role similar to the model in which I worked with Jason. The idea is that there isi someone consistently being mentored to take on the job should anything happen to me. A good succession strategy is vital in the precarious non-for-profit arts world.

To cite a specific example: the Indigenous Screen Office is a huge deal. That’s major progress. The fact that imagineNATIVE is now an international film festival with connections to many other Indigenous festivals around the world and that they look to us and ask for guidance, that’s incredibly rewarding since we have looked to others for guidance in the past. There’s a collaborative effort and ownership of who we are as people, working towards knowing our history and being about our histories. That’s why it’s important for everyone to understand the past. If I were the average Canadian, I would be furious with the information that has been withheld from me—I want to believe most Canadians feel this way. When the mass graves of children were uncovered at the Kamloops Residential School in 2021 it was the first time in my life I’ve seen an outpouring of outrage for us as a people. People all over the country were wearing orange shirts in solidarity on Canada day—nobody felt like celebrating. I’ve never seen that kind of mass support before.

Culture in a city can’t be reduced to one or two big events. What kind of a city do we want to live in? And if we keep going down this path it won’t end well. We need to think about arts organizations as investments: we’re investing in the health of the community and the city. I’m seeing a shift now where the priorities are changing depending on who’s in power, but decision-making always comes down to the economy. That shouldn’t be the only factor that informs policy but even if it is: festivals can measure their economic impact in the millions. The culture sector does not see any of that return.

A related initiative is our 2022 partnership with Reel Canada. We will be working with them again to provide programming for National Canadian Film Day which will bring Indigenous programming to various Cineplex Odeon theatres across the country.