← Explore

“If I have any allegiance with respect to the future of the planet it is not particularly with humans—it is with the manifold ways in which life produces intelligence, beauty, and sociality.”

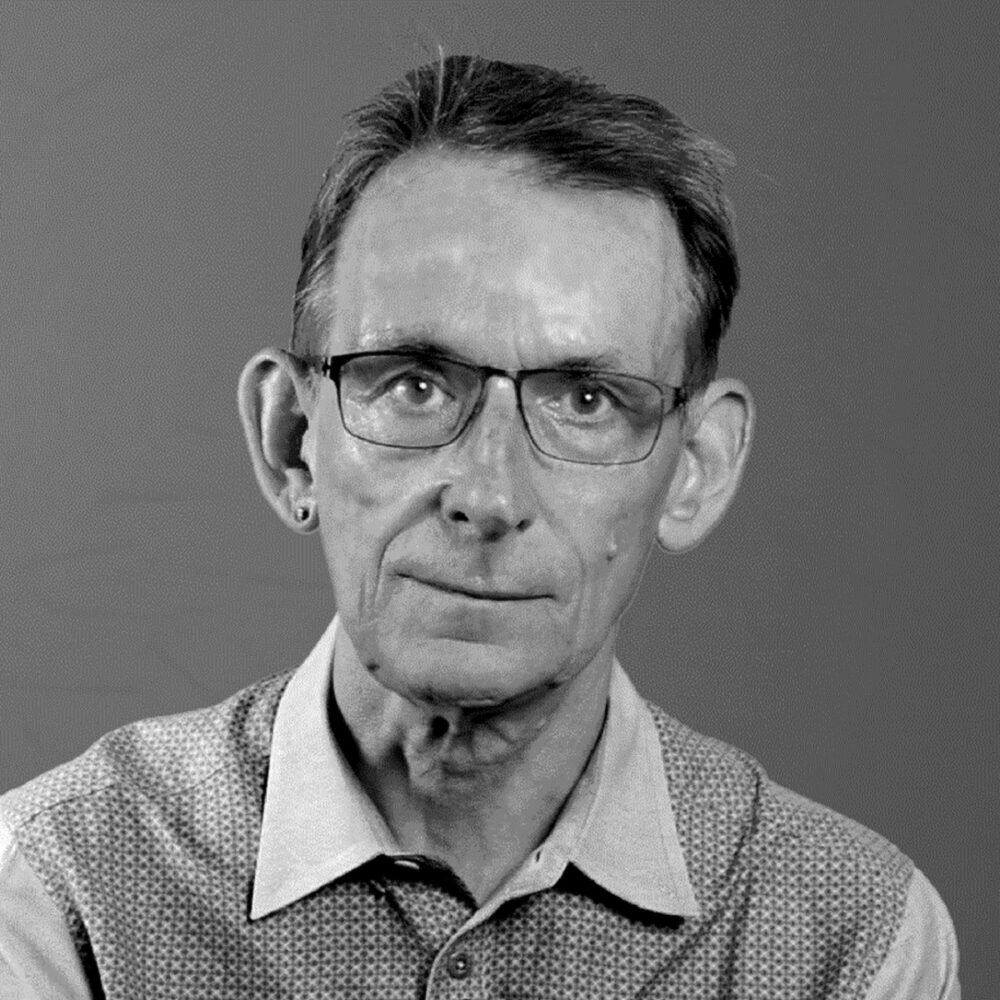

Geoffrey C. Bowker is Professor at the School of Information and Computer Science, University of California at Irvine, where he directs a laboratory for Values in the Design of Information Systems and Technology. Recent positions include Professor of and Senior Scholar in Cyberscholarship at the University of Pittsburgh iSchool and Executive Director, Center for Science, Technology and Society, Santa Clara. Together with Leigh Star he wrote Sorting Things Out: Classification and its Consequences (1999); his most recent book is Memory Practices in the Sciences (2005).

Q: In a number of your interviews with DISNOVATION you look to the natural world for examples of how humans might be able to address some of the issues we’re facing today. When it comes to the environmental crisis, what are the most important lessons we can learn from animals and other lifeforms?

A: One of the highly problematic historical assertions in the U.S. is that of American exceptionalism—the argument that there is something special about the country that makes it different from the rest of the world. A lot of thinking about humans with respect to the environmental crisis has been a form of species exceptionalism: we are different because we stand apart and above; we have rationality in our heads and tools at our fingertips. We gain a lot by saying that we are just another species. As Lynn Margulis first argued, symbiosis is a central fact about all life. We incorporate multiple species (our microflora and fauna), and we live in webs of connection. Unfortunately, we have a highly impoverished language for thinking about interconnections. We are a species like any other; it is unsurprising that some species have more interesting solutions to problems than we have thought of. Core to the human exceptionalism argument is that ‘we’ have intelligence and ‘they’ don’t. This is not only wrong, but deeply harmful: if I have any allegiance with respect to the future of the planet it is not particularly with humans—it is with the manifold ways in which life produces intelligence, beauty, and sociality.

“Attempting to freeze evolutionary change by creating natural reservations misses the point: we need to maximize the ability to speciate, to grow—by concentrating on conservation we make bad decisions for the long-term health of the planet.”

Q: For me, the most surprising statement you make is on biodiversity. You say, “Species are going to die, species die all the time, that’s not a problem.” Even though, logically, it makes sense, it still sounds quite shocking because it seemed to run counter to everything that we think we know about conservation. How did you come to this conclusion and do you ever get push back from airing views like this?

A: To start with the end and work back: yes, I do get pushback. I remember one encounter with an ecologist a number of years ago. He said that the role of conservation science was to preserve the maximum number of species in the present. I couldn’t disagree more. First of all, we’d do just as well to lose a number of ‘charismatic megafauna’—the game isn’t worth the candle. This is non-obvious, but it is about resources. An analogy is public health. In the U.S., an ungodly amount of money has gone into getting asbestos out of buildings—even though there really weren’t that many deaths involved; the same money spent on public health would have led to longer, happier lives for a far greater number of people. Focusing in on cuddly pandas because they are cute is really not the point. This has direct consequences for biodiversity policy. Attempting to freeze evolutionary change by creating natural reservations misses the point: we need to maximize the ability to speciate, to grow—by concentrating on conservation we make bad decisions for the long-term health of the planet. And back to my encounter—when pushed, he said that we should maximize species in the present since that’s when ‘we’ were living. This is such a silly and selfish argument: we should accept a slew of losses now and work for a robust future. This is not done through heroic efforts to protect.

Q: Another topic you talk about is geo-diversity. How does this differ from biodiversity and why should we care about it?

A: The basic argument here is that geo-diversity begets biodiversity. The more niches there are the better for specialized species to develop. A lot of human activity is about niche destruction: so even if we preserve some species, they won’t necessarily have a place to go—and they won’t have the opportunity to create new species since the ‘landscape’ of available niches will have been impoverished. The wider reason is that caring for the planet is about caring for all of the planet: soil diversity is a core issue which is very rarely considered; the planet is a process of which life is only a part.