← Explore

On View: Portrait de ma mère (1988)

“Molnar used a computer program to translate a soft, elegant, hand-coloured photograph of her late mother, Erzsi, into her own visual language of black-and-white geometric forms.”

“Molnar used a computer program to translate a soft, elegant, hand-coloured photograph of her late mother, Erzsi, into her own visual language of black-and-white geometric forms.”

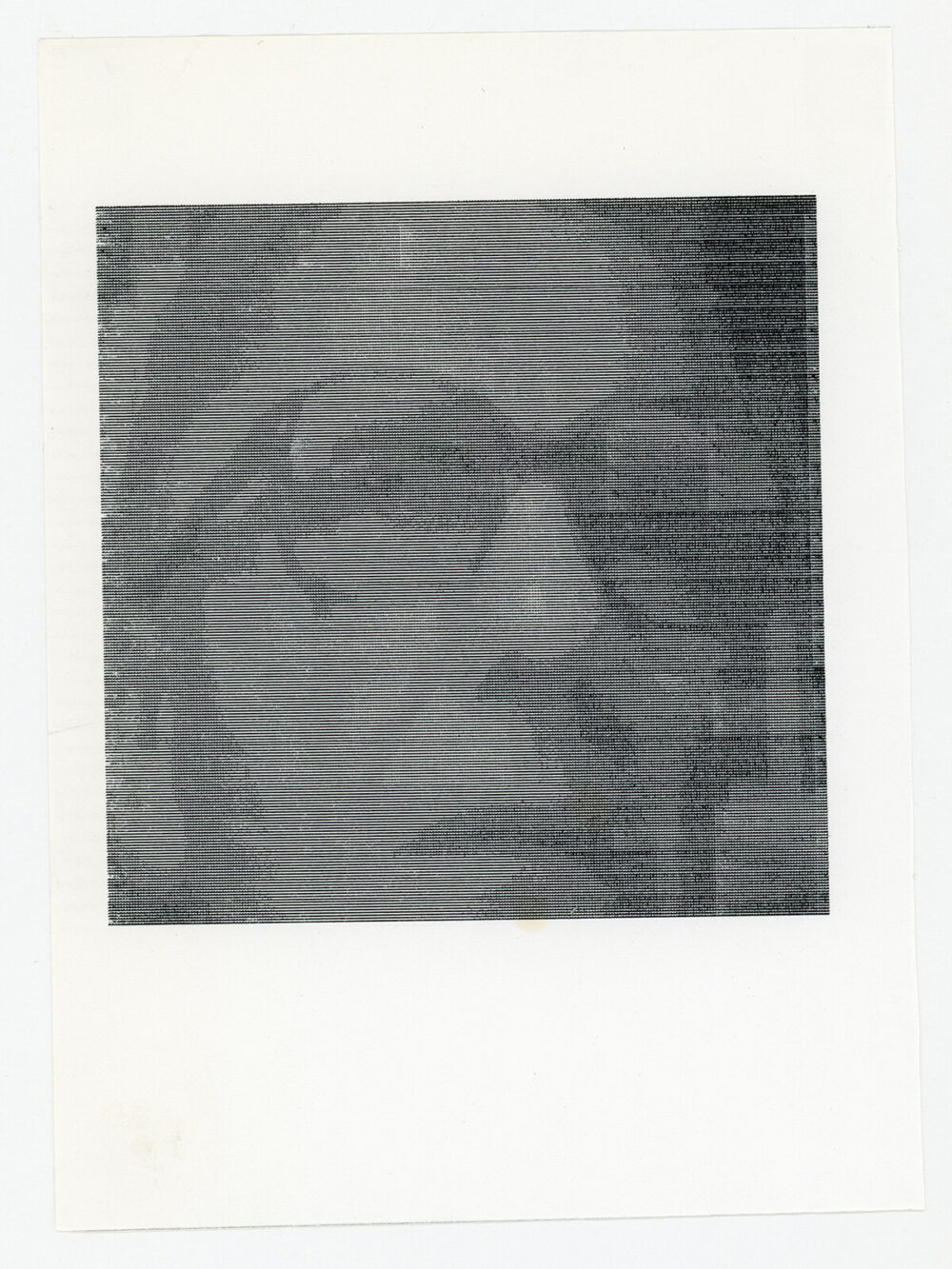

Vera Molnar, Portrait de ma mère, 1988, photo copies and plotter drawings on paper

Various iterations of the computerized portrait of her mother that Molnar created based on a photograph from the 1920s.

Various iterations of the computerized portrait of her mother that Molnar created based on a photograph from the 1920s.

“Portrait de ma mère atomizes the original photograph into small rectangles, the result somewhere between pointillism and ASCII art.”

In 1988, on the brink of major transition in Europe, Vera Molnar also shook things up in the studio. After nearly four decades of strict geometric abstraction, she made a portrait. Her first major figurative work since her twenties, Portrait de ma mère (Portrait of my mother) is still unmistakably hers, with its monochromatic minimalism and distinctive plotter-drawn lines. Molnar used a computer program to translate a soft, elegant, hand-coloured photograph of her late mother, Erzsi, into her own visual language of black-and-white geometric forms. Portrait de ma mère, alternately titled Portrait de ma mère en rectangles, atomizes the original photograph into small rectangles, the result somewhere between pointillism and ASCII art. At least eleven versions of the portrait exist, many of them bearing the grainy marks of a photocopier—within each variation there are more variations. In each portrait, Erzsi’s face seems to emerge from a hole in the page, her face serene, confident, legible as a portrait but not tremendously recognizable. We might even say it could be a portrait of anyone’s mother.

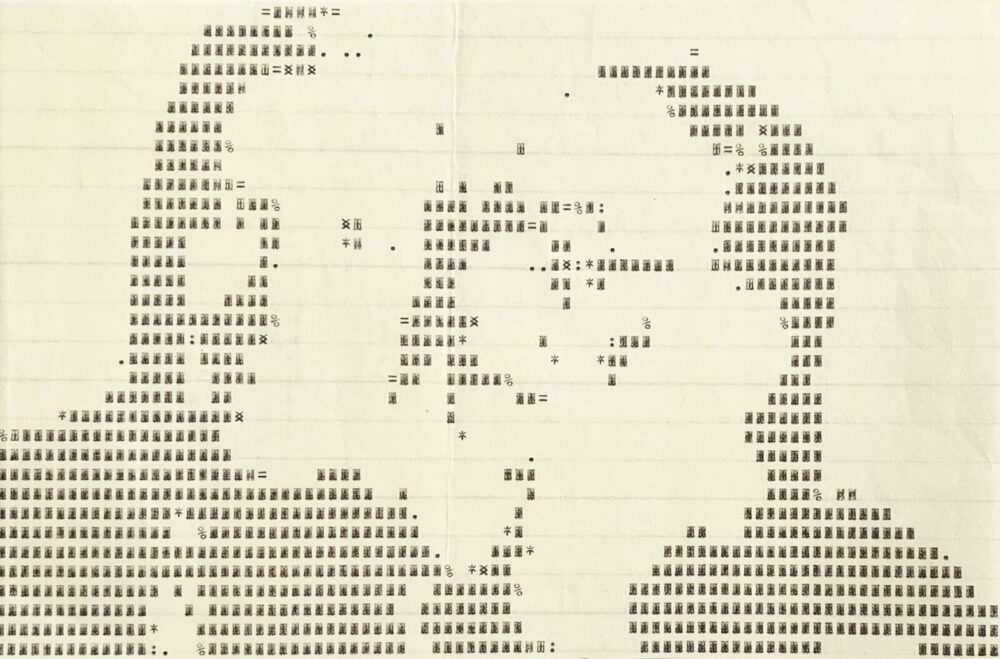

There is very little documentation of how this work was made, and Molnar’s own memory of the process is fuzzy. She recalls using a premade computer program, rather than one she wrote herself.1 Actually, this was technically not Molnar’s first return to figuration. In 1974, she and François Molnar visited Bell Laboratories in New Jersey with their friend Béla Julesz, a fellow Hungarian emigré who, like François, used computers in perceptual psychology research. They returned to Paris with a prized souvenir, a computerized ‘double self-portrait’ made from a snapshot of the couple. Like the small dots of a Seurat painting, the image is made up of small rectangles, asterisks, percentage signs, and other alphanumeric characters, drawn in black ink with a plotter. As in pointillism, the figures become more distinct when viewed from further away. We can make out François, looking straight at the camera, while Vera, recognizable by her glasses and chignon, appears to look past him. The yellowed, lined paper bears a crease, not down the middle, but exactly where their faces meet. Like Portrait de ma mère, this image was made using someone else’s program, and its style matches many computer-manipulated photographs of the era, from Harmon and Knowlton’s Computer Nude (1967) to Waldemar Cordeiro’s images of figures. Surely Molnar had the Bell portrait in mind when she returned to portraiture in the late ’80s. But the reference she chose to make was more art historical; she titled a series of seven portraits of her husband, made from digitized photographs but with a much denser matrix of characters, à la manière de Seurat (1988).

Vera Molnar, Double autoportrait de V. et F., 1974, 15 x 20 cm (archives of the artist)

A prized souvenir: The ASCII portrait of Vera and François Molnar was drawn during the couple’s visit of the Bell Laboratories in New Jersey.

A prized souvenir: The ASCII portrait of Vera and François Molnar was drawn during the couple’s visit of the Bell Laboratories in New Jersey.

“In 1974, Vera and François Molnar visited Bell Laboratories in New Jersey. They returned to Paris with a prized souvenir, a computerized ‘double self-portrait’ made from a snapshot of the couple.”

Vera Molnar, Portraits de F. à la manière de Seurat, 1988, 11 x 11 cm (Archives of the artist)

A series of seven portraits of Molnar’s husband, François, made from digitized photographs.

A series of seven portraits of Molnar’s husband, François, made from digitized photographs.

Molnar made Portrait de ma mère in dialogue with another series, Lettres de ma mère, a computer ‘simulation’ of Erzsi’s handwriting that is also included in the show, and which I will discuss in a later entry. The portrait graces the cover of an edition of screenprints of the letters made for the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, and it’s printed at the outset of her article “My Mother’s Letters” in Leonardo journal. By running Erzsi’s likeness through this program, Molnar’s early life collides with her life as an artist, as a pioneer of computer art.

Vera’s mother, like her beloved Mona Lisa, has an enigmatic smile, and like Leonardo’s famous portrait, Portrait de ma mère might be seen as blurring portraiture with self-portraiture. Though she could have easily included an untouched photograph of her mother alongside the Lettres, she decided to manipulate it, to abstract it almost to the point of anonymity. As with the asemic writing of the Lettres, Molnar takes something intensely personal and uses abstraction to make it more universally relatable. But this process of abstracting also becomes a sort of screen, which shields Molnar and her Mother from being seen too closely.

Vera Molnar, Portrait de ma mère, 1988, plotter drawing on paper, 5.5 x 4 in. / installation view: The Beall Center

for Art + Technology, Irvine, California (US) / Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection / photo: ofstudio

The plotter drawing (bottom) is shown with the related series Letters de ma mère that simulates her mother’s handwriting.

The plotter drawing (bottom) is shown with the related series Letters de ma mère that simulates her mother’s handwriting.

“Molnar takes something intensely personal and uses abstraction to make it more universally relatable. But this process of abstracting also becomes a sort of screen, which shields Molnar and her Mother from being seen too closely.”

Over the past five years, I have built a relationship with Vera Molnar that is rarely possible between artist and art historian. Any historian who has written extensively about a living practitioner knows that it can be equal parts exhilarating and frustrating. Molnar and I have a beautiful intergenerational friendship, but it involves a constant re-negotiation of boundaries, a shift between calling her Vera and calling her Molnar, as I have done in this essay without even realizing it.

I still remember our first phone call, in August 2017. It was a cold call, from my computer in Chicago to her landline in Paris. I rehearsed all the formalities, all the awkward turns of phrase that would signal my respect for the 66-year age gap between us. Growing up in the United States, I spoke Hungarian only with family, using tegezés, the most familiar form of address. Even as my circle of Hungarian friends widened as I grew up, the language still feels familial to me, as if speaking magyarul means we are at least distantly related. This rings especially true with anyone belonging to the Hungarian diaspora. As a heritage speaker, the prospect of having to use formal Hungarian makes me anxious, and using it to speak to a famous artist I admired only compounded the anxiety.

“How would Madame Molnar like to be addressed?” I shouted into my laptop for the third time in a patchwork of Hungarian and French words, my voice shaking. Silence. I feared I had said something wrong. I held my breath. Then, on the other end, laughter. “Nyuszikám,” she said in her sonorous, deep voice. “My little rabbit. I left Hungary when I was twenty-three. I don’t care about that sort of thing. You can call me Vera.”

“And yet, even as I peruse her archives and get closer to her, whether she is Vera the artist or Vera the pseudo-grandmother, I realize that I will never know her fully.”

I returned a laugh, relieved. It was more than just her irreverence toward stuffy hierarchies that I was grateful for. Her invitation meant more than a simple on peut se tutoyer. The only elderly person I had ever address this way in Hungarian was my grandmother. With a simple “call me Vera,” the distance between us seemed to collapse.

To this day, I don’t think our bond would be the same if we didn’t speak in our mother tongue. And yet, even as I peruse her archives and get closer to her, whether she is Vera the artist or Vera the pseudo-grandmother, I realize that I will never know her fully. The closer you get, the more the picture dissolves into tiny geometric forms.

References:

(1) The best we can do, to understand how the image was made, is to reverse-engineer it. To do this, I borrowed the technical expertise of my friend Jonah Marrs, who helped me see the portraits through the eyes of a creative engineer. We counted and measured the characters making up each variation of the portrait. Marrs suggested re-programming the work using an ASCII image generating program in Processing, replacing the alphanumeric characters with box-drawing characters, which are semigraphics typically used to draw geometric frames and boxes.

╠ ╵ │ └ ├ ┘ ┤ ┴ ┼

▁ ▂ ▃ ▄ ▅ ▆ ▇ █ ▉ ▊ ▋