← Explore

1950–1960: Partners in Crime

“Close friend François Morellet would refer to Vera and husband François Molnar as un peintre à deux têtes, a two-headed painter.”

“Close friend François Morellet would refer to Vera and husband François Molnar as un peintre à deux têtes, a two-headed painter.”

Vera Molnar in her home/studio, rue de Gergovie, Paris, 1954 (scanned medium format negative; photo by François Molnar, Vera Molnar archives, used with permission of Vera Molnar)

“Without the signatures, it’s nearly impossible to tell the solo and collaborative works apart. The couple painted according to a shared ideology that de-emphasized individual authorship.”

During their first decade in Paris, Vera and her husband François Molnar often made paintings and collages collaboratively. Their close friend François Morellet, who they met in 1957, would refer to them as un peintre à deux têtes, a two-headed painter. In Vera’s words, they had “two optics, each with their own ideas of variations.”1

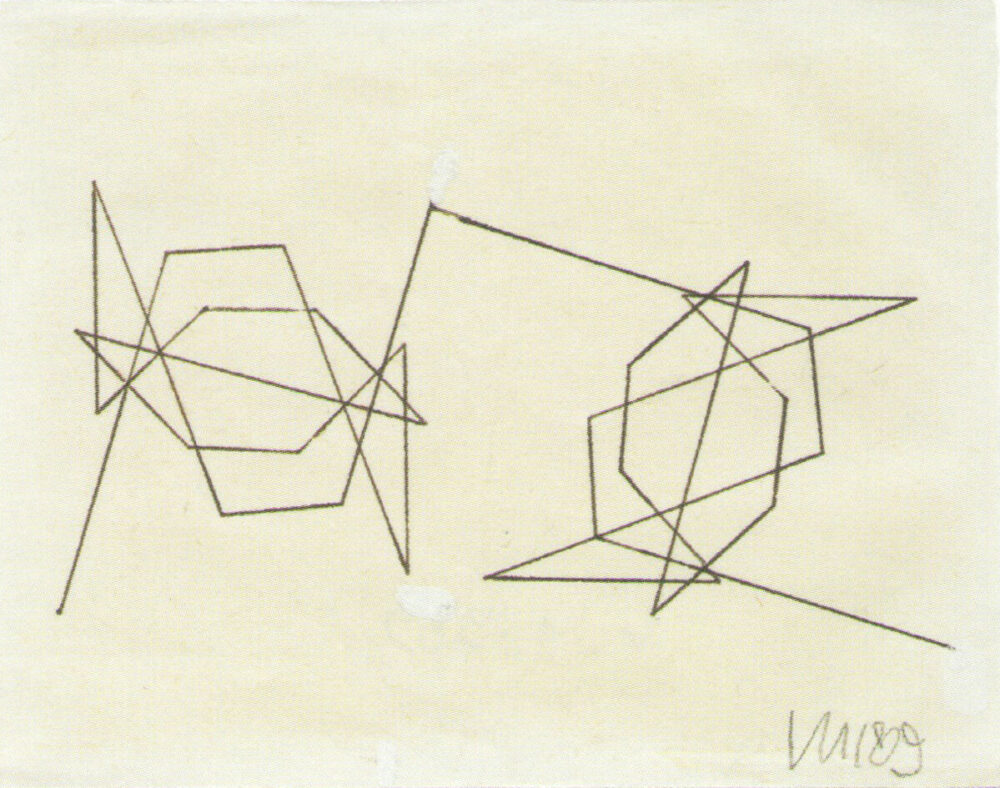

Their collaborations usually took place at the planning stage of a painting or large-scale collage. The Molnars would pin paper cutouts to the wall of their home/studio, and alternately make modifications until they agreed that the composition was finished. Then, Vera would do the painting and gluing, since of the two of them she was more enthusiastic about the materiality of making pictures—the smell of turpentine, the sound of graphite sliding along a sheet of paper.

Not all of Vera’s 1950s works were made with her husband. In a photo from 1954, she sits at her desk against a tall Parisian window, under a collage titled Douze Rectangles that is now held at the Musée de Grenoble along with many of their co-signed canvases. This one bears only her signature. Without the signatures, it’s nearly impossible to tell the solo and collaborative works apart. Not only did the couple paint according to a shared ideology, very much in current with the postwar Concrete Art movement, but this very ideology emphasized a ‘rational’ methodology that de-emphasized individual authorship.

The Molnars didn’t follow this path for long. After co-founding the Centre de Recherche de l’art Visuel (CRAV), later known as GRAV, in July 1960, the couple left the group only four months later, citing a fundamental disagreement over the definition of ‘research.’2 They made their last co-signed canvas, Effet esthétique de l’inversion des fonctions par la fluctuation de l’attention, in 1960, exhibiting it in Max Bill’s landmark exhibition “Konkrete Kunst” in Zurich that same year. Then, François Molnar ‘quit’ art, turning his attention to scientific research in perceptual psychology and experimental aesthetics. I argue in my dissertation, however, that the Molnars’ collaborations did not really end there. Rather, they took on a different shape. For the next three decades, until François’s death in 1993, the couple remained each other’s primary interlocutors, Vera’s painting influencing François’ research and vice versa.

“Until his death in 1993, the couple remained each other’s primary interlocutors, Vera’s painting influencing François’ research and vice versa.”

References:

(1) Deiss, Amely, and Vincent Baby. “Entretien avec Véra Molnar.” In Véra Molnar: Une Rétrospective, 1942-2012, edited by Sylvain Amic, 15–19. Couleurs contemporaines. Paris: Chauveau, 2012, 18.

(2) François Molnar, “Lettre de démission / Letter of resignation, 30.11.1960,” in GRAV, Groupe de recherche d’art visuel, 1960-1968: stratégies de participation: Horacio Garcia Rossi, Julio Le Parc, François Morellet, Francisco Sobrino, Joël Stein Yvaral: 7 juin-6 septembre 1998, Magasin—Centre d’art contemporain de Grenoble, ed. Yves Aupetitallot (Grenoble: Le Magasin, 1998), 59–61.

This letter suggests that the disagreement was primarily François’ and that Vera left in solidarity, along with the artist Servanes.