Economies

Reader

Matthew Braga explores prosperity and precarity for the artists and cultural workers whose true value will never be measured in dollars.

The Digital Economies Reader builds on the Digital Economies Lab (DEL), a year-long exploration of the wonders and anguish of making art and culture in the twenty-first century organized by Ottawa’s Artengine.

Lead Writer

Matthew Braga

Residents

Izzie Colpitts-Campbell

Julie Gendron

Lee Jones

Suzanne Kite

Emmanuel Madan

Tim Maughan

Jerrold McGrath

Kofi Oduro

Kalli Retzepi

Macy Siu

SWINTAK

Type Treatments

Tim Rodenbröker

Artengine Team

Ryan Stec

Remco Volmer

Kseniya Tsoy

Steering Committee

Jeremy Bailey

Sarah Brin

Jen Hunter

Artengine is an Ottawa-based artist-run centre that brings together artists, designers, technologists and researchers to explore the social impacts of emerging technologies through collaborative learning and production.

The Digital Economies Lab (DEL) is a year-long exploration of the wonders and anguish of making art and culture in the twenty-first century. Drawing on in-depth research, dialogue with experts, engagement with the public and media arts professionals, DEL’s residents are producing prototypes and proposals for increasing sustainability and resilience in the creative sector.

© 2022 HOLO

“Artists who lose the lottery for grants, residencies, and corporate patronage work second and third jobs to subsidize their much less lucrative art. It often feels like the only people who can afford to make art at all are the people who don’t need money at all.”

When will I feel like I’ve finally made it? It’s something I think about a lot as a writer trying to make a living off my work. There are the critical markers of success, like writing stories that have an impact, are widely read, or appear in prestigious publications. But I don’t think I’ll ever feel like I’ve truly made it until I’m no longer worrying about precarity—until I feel like I’m fairly, properly, and promptly compensated for my work.

I know I’m not alone! Musicians get paid mere fractions of a cent for every stream of their songs and have to relentlessly tour and sell merch to get by. Disney is eating the film world, at the expense of independent and experimental film. The diverse, affordable, working-class neighbourhoods where artists once lived and worked—painting, sculpting, constructing, showing—are now luxury condos and high-end boutiques. Artists who lose the lottery for grants, residencies, and corporate patronage work second and third jobs to subsidize their much less lucrative art. It often feels like the only people who can afford to make art at all are the people who don’t need money at all.

Add a global pandemic to the mix, and things aren’t looking great right now for people who want to make a living making art. What will it take to help artists prosper? Is there a way forward outside capitalism? Can we—or should we—still rely on government funding, or corporate support? No one knows! Not yet. But as terrifying as that may be, there’s also excitement in the unknown, because it means we have an opportunity to conjure new, experimental, hopefully better futures into existence to replace what exists now.

“With the Digital Economies Reader we’ll be publishing short interviews with the artists involved, more information about their projects, links to stories and resources you might find interesting, and some of my own thoughts on trying to make a living as a writer.”

In January, I joined a group of artists who descended upon Ottawa to imagine what some of these futures might look like—futures more equitable and sustainable, where artmaking is more broadly valued, and where it’s possible to make a living making art. Some proposed an artists’ union that could push for better working conditions and support by leveraging the collective strength of artists across disciplines, a collective too large to ignore. Others advocated for ways to make resources, funding, knowledge, and skills more widely available and accessible—especially among artists with children, marginalized artists, and artists of colour, who often lack the same privileges, opportunities, and benefits available to their white, cisgender, heterosexual colleagues. Clearly, the business models and financial supports that have funded artmaking for decades aren’t working, or aren’t working equally, if they ever worked at all, and the artists at this workshop were eager to come up with something new—such that anyone who wants to be an artist, who wants to make art, can feel welcome, supported, and secure. The meeting, organized by the Ottawa collective Artengine, marked the start of a year-long exploration: the Digital Economies Lab (DEL).

Over the coming months, the DEL’s artists will present some of their ideas to the wider artistic community for feedback, insight and support. With the Digital Economies Reader we’ll be publishing short interviews with the artists involved, more information about their projects, links to stories and resources you might find interesting, and some of my own thoughts on trying to make a living as a writer. Running themes will include: how automation, AI, and tech-assisted tools are changing the way artists work; how universal basic income and other forms of government support might alleviate the feeling of precarity; the impact of corporate funding on who gets to make art, and the kinds of art that gets made; and why art-making isn’t valued the same as other types of work. I hope you’ll come away with a greater appreciation of the uncertainty and precarity facing today’s working artists—and optimism that things can change.

“When tales of artist struggle are rooted in the experience of individual artists or bands, the public response is often to push back and discredit, to find fault in the story or suggest the individual is not a credible spokesperson for the problem he or she is articulating…. It’s not a matter of dredging up a more appropriate poster child for the starving-artist cause. If we want to improve the lot of artists, we need to shift gears from a woe-is-the artist conversation to one about the importance of art and the need to support the creation of art at the societal level.”

“The Digital Economies Lab exists because the world was broken even before the pandemic. The motivation for bringing the Lab into being was really trying to find new models and new ways for artists to find the life of an artist to be sustainable.”

Ryan Stec and Remco Volmer are the Artistic and Managing Directors of Artenngine, an Ottawa-based non-profit center for art and technology and initiators of the Digital Economies Lab (DEL). Ryan is an artist, producer and designer working in both research and production, and a PhD candidate at the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism, Carleton University. Remco is a researcher, producer and collaborator; a graduate of Utrecht University of Art’s Creative Media program, his practice is focused on technologically mediated collective experiences.

“It’s like a very long marathon that we’re running, but we need to shift the world from right-place, right-time privilege to, ‘if you work and you are passionate, you get access and you can achieve success,’ right?”

Jeremy Bailey is a Toronto-based self-proclaimed “Famous New Media Artist” and Head of Experience at FreshBooks. Bailey believes that technology done right empowers us all to be famous, and he has taken that positivity and channeled into the Lean Artist program, a project he initiated to catalyze artistic imagination by drawing on strategies and models from the startup world. Along with Jen Hunter, Jeremy served on the DEL steering committee, and helped shape the program undertaken by its residents.

“If there’s one good thing to come out of this year’s global pandemic, it’s that a lot of people are suddenly talking about universal basic income. What was once a relatively fringe concept is now very much mainstream.”

As a short-term measure, governments have been putting money into people’s pocket (in Canada, for example, more than 8 million people have applied to receive $2,000 each month through the CERB program). The schemes haven’t always been perfect, but they’ve offered a lifeline for many—especially precarious workers, freelancers, artists, and creative types, for whom steady, well-paying work is elusive at the best of times. It’s not hard to imagine what life might be like if governments did this all the time.

If there’s one good thing to come out of this year’s global pandemic, it’s that a lot of people are suddenly talking about universal basic income (UBI). What was once a relatively fringe concept is now very much mainstream. Is it any surprise people are looking for new means of support? The pandemic has upended our jobs, our social circles, the niceties of daily life. Everyone knows someone who’s been laid off, or who’s struggled to find work. Maybe that someone is you. It’s clearer than ever that the support systems so many people rely on to make a living are far more fragile than they appear.

At the same time, we’ve been witnessing social unrest on a scale not witnessed in years. People across America and other parts of the world have turned outrage over the killing of George Floyd by a Minnesota cop into widespread protests against police brutality and systemic anti-Black racism. The possibility of defunding and abolishing the police has taken hold like never before. If you want to talk about how we fund a guaranteed income for all—along with access to housing and mental health support—the disproportionate amount of money cities spend on police is a pretty good place to start. For people who spend their lives making art, UBI has an important advantage over the traditional supports of residencies, patrons, philanthropies, and grants. Adopting UBI doesn’t just benefit artists. It could lift everyone out of poverty. Everyone wins.

“A guaranteed income could help level the playing field for Black and Indigenous artists, whose practices are often overlooked and ignored by white-run institutions and funders.”

A guaranteed income could decouple the necessities required to live—food, housing, healthcare—from the work that artists do to make a living, much of it entirely unrelated to the work of artmaking itself. Artists could make art without—or in opposition to—the pressures of the market, without worrying about what will sell or appeal to donors, grantmakers, gallery owners and brands. It could help level the playing field for Black and Indigenous artists, whose practices are often overlooked and ignored by white-run institutions and funders. And as much as it feels like artmaking has never looked so precarious, it also feels like there’s never been a better moment to push for new supports and safety nets that not only help us recover, but set us up to thrive.

“The institutions that have undergirded the existing system are contracting or disintegrating. Professors are becoming adjuncts. Employees are becoming independent contractors (or unpaid interns). Everyone is in a budget squeeze: downsizing, outsourcing, merging, or collapsing. Now we’re all supposed to be our own boss, our own business: our own agent; our own label; our own marketing, production, and accounting departments. Entrepreneurialism is being sold to us as an opportunity. It is, by and large, a necessity. Everybody understands by now that nobody can count on a job.”

“I think a lot of artists have this problem—the constant switching between a wealth of admin work, survival work, activist work, creative work and homework. It’s not the biggest problem we have, but it is definitely an annoying one that is also very much woven into people’s socioeconomic status.”

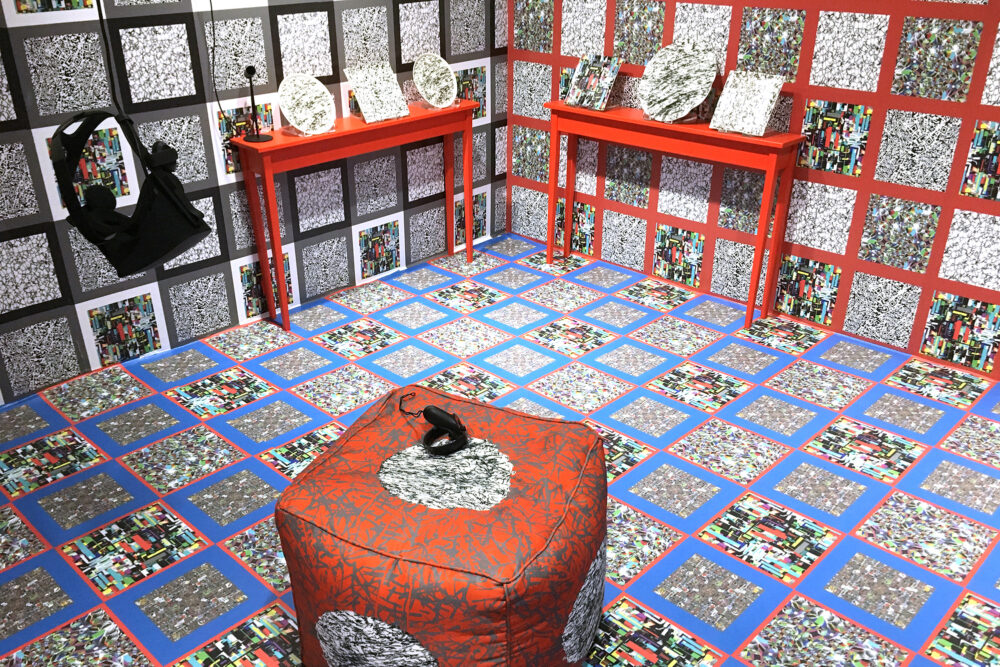

DEL resident SWINTAK is an interdisciplinary artist, educator and context-maker based in Montreal. Her past projects often involve large-scale installations built onsite and integrated with the surrounding context. Examples include moving an entire house by hand without the aid of machinery, constructing the most banal roller coaster ever made, and attempting to give a shed consciousness.

“Whenever it is possible, I try to make space by having computer and phone free times. Sure, I might be hard to reach, but most things can wait. Having the time to percolate is so easily overlooked, yet it has such great value.”

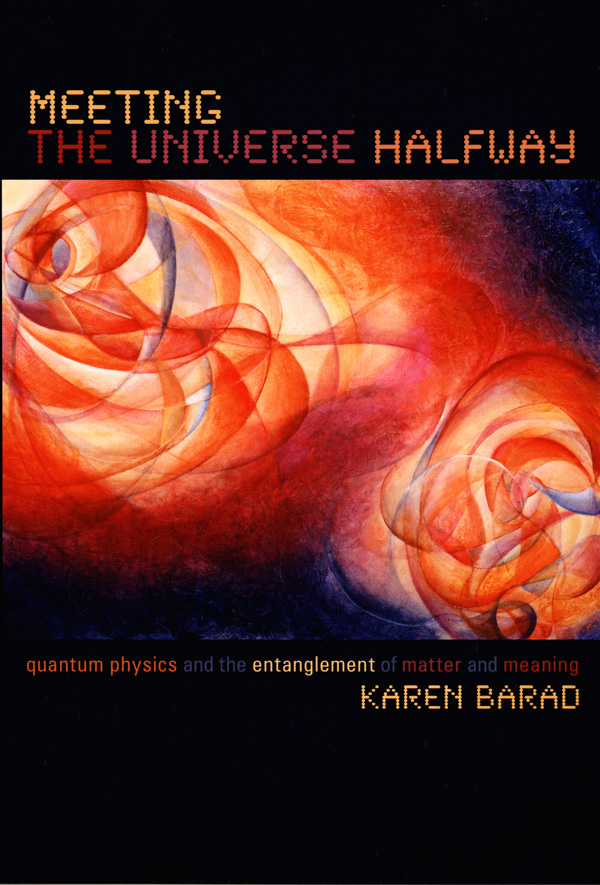

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007)

“As industries across the board line up for bailouts, it is time to assert culture as an essential industry and map out a role for the arts that would have seemed unimaginable weeks ago. A new Federal Art Project probably wouldn’t be devoted to mural painting, but it could offer an alternative to a flailing market and channel artworks into public collections. Museums, now supported through tax-deductible donations, could receive more direct public funding in exchange for offering free admission. Private markets and philanthropy will be changed on the other side of this pandemic, so it is time once again to envision what art looks like as a public good.”

DEL Pitch: An Anti-Airbnb Experience

“Our project looks at the way artists have changed radically over the last couple of decades while funding and distribution has remained the same, but by taking a different approach or ideology. We are looking at a system that provides expression to be at the frontier—elements of randomness—and take away from the super-curated feelings that run today’s world.”

Outline:

The perception of an artist is one that is weird when dissected. People often overlook the arts when these are experts in their own craft, and a lot of people have daily interactions with a creative output. Our project looks at the way artists have changed radically over the last couple of decades while funding and distribution has remained the same, but by taking a different approach or ideology. We are looking at a system that provides expression to be at the frontier—elements of randomness—and take away from the super-curated feelings that run today’s world. This ensures that a multitude of artists, curators, and other engagements in the arts can be more natural. By providing everything from knowledge circles to “anti-Airbnb” experiences that derive from random encounters, we hope to stimulate conversation and ideas on how artists can work in the future.

Team:

Kofi Oduro & SWINTAK

01 – Reference

Roughness, randomness, the uncurated: these aren’t bad things as inspiration can be drawn from anything. Art doesn’t need to be inspired from the same artists, the same ideologies, or even the same region. It can be mustered from the simplest of sources—like the way your bed squeaks at night, the way your water faucet still drips, no matter how tightly you turn the knob. This is what this image represents: the notion that there is more than one way to appreciate art, and that maybe that is the approach funding and distribution should take.

02 – Collaboration

Even during uncertain times there are rays of light and brightness, as long as we look at what is right and guided.

03 – Preview

The ideas are there, they are brimming. We have what we want to do, we’ve tested it out in small settings and have asked questions. But even with work, it is still in the prototyping stage; hence an incomplete planet. At the same time, with the brightness of the image, we believe in the idea and what it stands for. Potentially, it can be used to achieve long term goals, case studies and other factors. Ideas are only a small gesture, but a small gesture can make sparks.

“When will audiences return to live events and cultural institutions? And with limits on crowd sizes, how can anybody budget for a venue they can only fill to one-third capacity? Maybe digital alternatives will replace the live arts, but will people pay for the virtual experiences they’re currently enjoying for free? As arts leaders debate these questions, a picture is emerging in which the micro and the local are as likely to succeed as the grandiose and the institutional, and the virtual will flesh out the actual. The economics, however, remain murky.”

“Back in the day, you found an artist randomly, watching MuchMusic, or MTV, or on the radio. Since we’re not engaging with these formats, and everything is curated for us, it’s hard for some artists to get discoverability.”

DEL resident Kofi Oduro’s artistic practice is an observation of the world around us, which he then inserts into artwork for others to relate to or disagree with. Through videography, poetry and creative coding, he tries to highlight the realms of human performance and the human mind in different scenarios. These situations can be described as social, internal, or even biological, which we face in our everyday lives.

“I hope that in the longer-term UBI would allow for the blurring of art and life, allowing us to approach problems in more creative ways and reconstruct society to address systemic issues. This would not mean that everyone would suddenly become artists, but art would lose the elitism attached to it. Giving more people access to making art or having creative outlets, would foster a wider appreciation for the benefits of art and what it can be (not just painting and sculpture). This would also help to challenge what is understood as culture and flatten the hierarchies of high and low culture. Going to watch football and having a drink in the pub is culture and just as valuable as a trip to an art gallery or museum.”

DEL Pitch: Artists as ‘Alternative Consultants’

“After a big storm or fire, fungi and bacteria move in and liberate resources from the destruction so that new growth might emerge. Following COVID-19, how might artists and other creators be recruited into the process of decomposing the debris following the pandemic and quarantine to support new models to emerge?”

Outline:

COVID-19 is revealing the fractures in the systems intended to support us. We will see considerable institutional failure in the coming months and years. After a big storm or fire, fungi and bacteria move in and liberate resources from the destruction so that new growth might emerge. Following COVID-19, how might artists and other creators be recruited into the process of decomposing the debris following the pandemic and quarantine to support new models to emerge? Networks of cultural production differ in form and intention from media, manufacturing, supply, and other global systems. However, by superimposing creators and their structures of production onto other systems experiencing stress and collapse new sources of value can emerge, be synthesized, and support a new cycle of emergence. One job of the artist is to see the world. By imagining artists as ‘alternative consultants’ other sectors can better see the aftermath of the pandemic on their traditional activities and imagine paths forward outside of habitual and often ossified routines.

Team:

Jerrold McGrath

01 – Reference

The phrase “stop watering dead plants” serves as a reminder and a gesture toward grieving in the work. Decay is not immoral. Regeneration requires loss.

02 – Collaboration

This work is being expanded through New Not Normal, a crowd-sourced emotional map of responses to COVID-19.

03 – Preview

Working with a company in Halifax we have secured our first opportunity to practice this approach in an authentic setting.

“The alternative consultant is in there to examine unexamined sources of value. And value not necessarily in an economic sense. There are raw materials present in organizations with a long history that are likely not seen. But there are absolutely routines that become ossified over time that also need interrupting.”

DEL resident Jerrold McGrath explores how culture can play a more active role in complex systems challenges such as economic inequality, climate change, decolonization, and artificial intelligence. Following several years as a cultural consultant in the Japanese automotive industry, he served as the director of innovation at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, program director at Artscape Launchpad and continues to work with organizations and projects that span sectors and geographies.

“I have my consultancy, and to be honest, I’m sick of it. I shudder every time I say the word consultant, and so the opportunity to sort of play around with that, to turn my own dying consultancy into that is really exciting to me.”

David Cayley & Charles Taylor, The Rivers North of the Future: The Testament of Ivan Illich (2005)

“Although some institutions have introduced diversity initiatives, progress seems slow and tied up to arts funding structures that are temporary and one directional—ultimately serving the institutions rather than the ethnic minorities they seek to engage. Organisations may gain funding by appealing to funders’ diversity agendas, but their engagement with ethnic minority communities and artists is rarely sustainable or lasting, leaving creatives feeling exploited and perhaps further marginalised.”

“In 2018, Christie’s auctioned its first piece of AI-generated art—a vaguely eighteenth century-looking portrait—which, according to The Verge, was created with ‘borrowed code’ and wrapped in an alluring but ultimately misleading narrative of a self-determined computer creating art.”

I’ve been watching an increasing number of artists experiment with machine learning in all kinds of interesting ways. The writer Robin Sloan has been writing a novel with suggestions from an algorithm trained on old sci-fi and fantasy novels—a word here, a phrase there, curated fragments plucked from the ether, generated based on what Sloan has written so far. The musician Holly Herndon created her most recent album using musical contributions from a machine learning algorithm trained on a choir of Herndon and her collaborators, resulting in a haunting digital feedback loop that resembles their voices but is a performer all its own. And for days, earlier this Spring, I couldn’t stop thinking about the work of artist Cyril Diagne: a prototype of an app that functioned, essentially, as a copy-paste button for the physical world. Diagne took a picture of a dress on a wall, pointed their phone at a laptop, and the dress magically, almost immediately, lept to the digital canvas on the laptop’s screen.

But there are other experiments that give me pause. OpenAI recently introduced Jukebox, a machine learning algorithm that generates new songs in the style of popular artists—from the Pet Shop Boys to Nicki Minaj—after being trained on libraries of their music (there are some unnerving examples, but a lot of bad ones as well). A musician and machine learning developer offered a thoughtfully detailed critique. In 2018, Christie’s auctioned its first piece of AI-generated art—a vaguely eighteenth century-looking portrait—which, according to The Verge, was created with “borrowed code” and wrapped in an alluring but ultimately misleading narrative of a self-determined computer creating art. The ethically fraught world of deep fakes looms large, and work that incorporates image and facial recognition algorithms—and all their inherent biases towards race and gender, embedded by those who trained them—have so far presented the biggest concerns of them all.

“It’s tempting to think algorithms and automation could help level the playing field in a world that is already uneven … freeing overworked and underpaid artists to pursue the aspects of their art that are most enjoyable, creative, or personally fulfilling.”

Creatively, there’s an abundance of potential uses. But that doesn’t mean moral or ethical considerations can be ignored. I know that it won’t be long before machine learning algorithms enter the realm of the mundane, and are just another tool in the toolbox to help artists create more quickly, effectively, efficiently than performing the dull or repetitive tasks we could scarcely imagine automating before. It’s tempting to think this could help level the playing field in a world that is already uneven, especially when you have artists competing against other, more privileged artists with more money, more time, more comfortable living situations—freeing overworked and underpaid artists to pursue the aspects of their art that are most enjoyable, creative, or personally fulfilling. But at the same time, I think we have to be skeptical of the way these tools might be used to devalue artists, or exploit others.

It’s encouraging to see how both Sloan and Herndon have tried to account for this—Sloan, by acting as a curator and interpreter of the algorithm’s output, and Herndon, by only feeding the algorithm data derived from consenting collaborators. If these tools are to be part of the discussion around artist prosperity, artists can’t lose sight of the fact that the tech companies and communities that develop these tools have different imperatives than artists do. The way artists use them should be different, too.

“I still dream of making enough money from selling a novel every two or three years to not have to do anything else, but looking at the publishing market that’d involve me having to produce such mediocre work that it’d make the whole venture completely pointless.”

DEL resident Tim Maughan is an author and journalist using both fiction and non-fiction to explore issues around cities, class, culture, technology, and the future. His work regularly appears on the BBC, New Scientist, and Motherboard. His debut novel INFINITE DETAIL was published by FSG in 2019 and was picked by The Guardian as the best science fiction and fantasy book of the year.

“In the pay-per-stream model, artists are motivated to accrue spins, rather than devoted fans, by any means necessary. A catchy three-minute earworm that begs to be played ad nauseam generates more revenue than a longer, less repeatable track, even if the same number of people listen to each song every month. Artists are responding to this financial incentive by releasing shorter songs more frequently. But musicians like Vermont-based cellist Zoë Keating, whose instrumentals can be as long as eight minutes, lose out by not making songs that adhere to norms of radio-friendly consumption.”

“Artist-run centres or collectives who are racialized, Black, and doing the work—many of them are new. Given the cycles of how people come into funding, it means they’re starting somewhere closer to the bottom, as opposed to at the top, where traditional institutions have been funded over time and have established themselves.”

Andrea Fatona is an independent curator and associate professor at OCAD University. Her PhD research examined equity in funding from Canada Council for the Arts for Black and other racialized artists during the 1980s and 1990s. Fatona is currently working on an online platform to host the works of Black cultural producers, critics, and craftspeople with practices in Canada between 1989 and the present.

Q: In the U.S. there is a stark disparity between funding for large cultural institutions versus racialized artist-run centres—does that only widen the gap, or amplify issues of visibility?

A: I think it amplifies it more than it widens. Because I think most artist-run-centres I know of, and the ones I work with, are doing the work. In terms of resources available to do the work, they’re getting significantly less support. I think the other thing about artist-run centres or collectives who are racialized, Black, and doing the work—many of them are new. Given the cycles of how people come into funding, it means they’re starting somewhere closer to the bottom, as opposed to at the top, where traditional institutions have been funded over time and have established themselves. And I believe that newer institutions are having to establish themselves and do the work to prove themselves to get to the level of funding that traditional institutions are at—although I think that newer institutions are doing much more interesting work in terms of equity and inclusivity. So that’s where I think the issue lies, in terms of funding going to organizations who, on the surface, are taking up this issue of diversity, not inclusion. It’s about getting a number of bodies through the space, or having a number of racialized bodies within the institution, but they’re not necessarily in positions of power where they’re making decisions that would actually open up the institution’s practice of equity.

“I want to be optimistic, to tell you the truth; I really want to be optimistic. My optimism is not necessarily for traditional institutions, it’s for the racialized artists out there making these demands.”

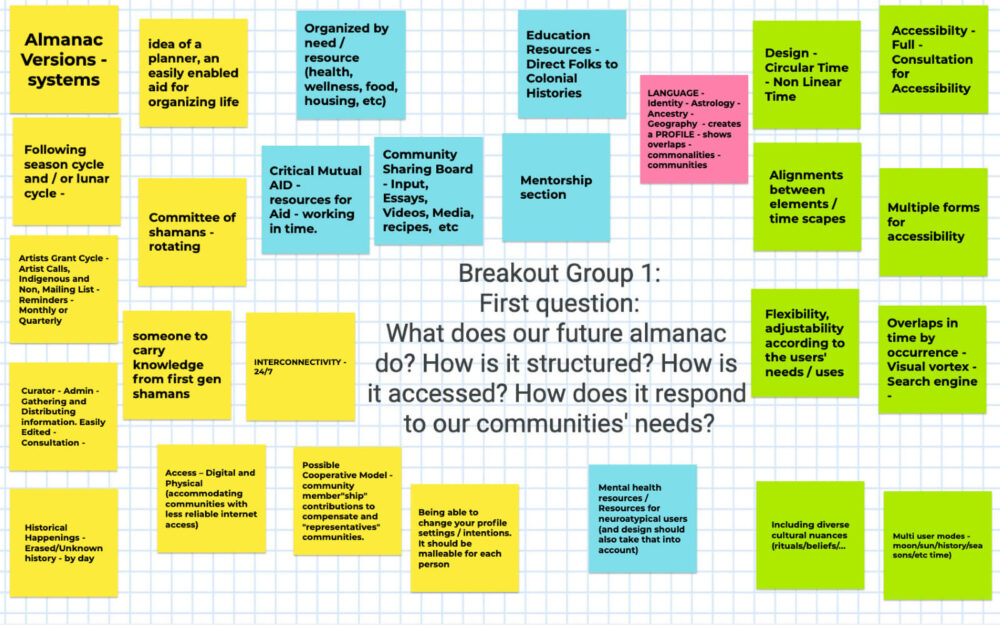

DEL Pitch: An Artist’s Almanac

“My research project is to create an Artist’s Almanac, a tool for U.S. and Canadian artists, especially Indigenous artists and marginalized artists. I have observed that while resources and information are available, it is difficult to access them easily and quickly, causing confusion and hopelessness for members of our community.”

Outline:

My research project is to create an Artist’s Almanac, a tool for U.S. and Canadian artists, especially Indigenous artists and marginalized artists. I have observed that while resources and information are available, it is difficult to access them easily and quickly, causing confusion and hopelessness for members of our community. How can we transform access to resources and information, so that artists are more successful and have tools at their fingertips?

We believe access to already available resources and information is the first step to assessing what resources are needed for artists, especially Indigenous artists and marginalized artists.

We will know we’ve collected resources and information in a helpful way when we see the following feedback from the community: folks engaging with the platform over its first year.

Team:

Suzanne Kite

01 – Reference

How to Build Anything Ethically Suzanne Kite, illustrated by Kari Noe (2019). These graphics represent the starting point of my thinking of ethical protocols, and imagining how those protocols can be reflected in the design of a resource to find further resources.

02 – Preview

The Almanac seeks to “imagine backwards,” from a future where Indigenous and marginalized artists have access to the resources they need and want, to the present, where such information is collected into clear, legible, and printable resources. The summation of my work will be presented when I host a public roundtable that brings collaborators and co-conspirators together.

03 – Collaboration

I meet with the team at Concordia University’s Feminist Media Studio over Zoom to plan our next steps, a series of workshops with co-facilitator Alisha Wormsley and fellow artist and thinkers.

“There is a cultural acceptance that the work of artists is different in essence than the work of other professionals, but it is harder to pin down what, exactly, constitutes that difference. Being an artist is widely perceived as a matter of choice and a question of privilege, rather than one of sacrifice that merits financial reward.”

“I fund my art by siphoning off parts of artist fees from gigs, grants, scholarships, and fellowships to live and make art in the margins of research, academia, and project funding.”

DEL resident Kite aka Suzanne Kite is an Oglála Lakȟóta performance artist, visual artist, and composer raised in Southern California, with a BFA from CalArts in music composition, an MFA from Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School, and is a PhD candidate at Concordia University. Kite’s scholarship and practice highlights contemporary Lakota epistemologies through research-creation, computational media, and performance.

“So that’s my audience—the person who’s like ‘how do I make money as an artist?’ It’s a person, hopefully anywhere in the world looking for international residencies. Residences that let you bring your baby, residencies that provide childcare. Tools for that kind of thing exist, but they require so much research and insider knowledge.”

“Under President Trump, the relatively modest U.S. budget for arts spending—of the National Endowment for the Arts’ $148 million budget in 2016, only $8 million went to programs for music, including opera—is now on the chopping block. The downturn isn’t just happening in the States: More countries with generally higher levels of cultural spending seem to be acting more like America.”

“I think of funding my artistic practice in two ways: personal stability and project stability. One allows me to pay rent and wear cool sneakers; the other pays for the material costs of producing art.”

DEL resident Izzie Colpitts-Campbell is a designer who works with the body, leather, code and computational fashion. She currently works as a UX Lead on Platform at Shopify where she works designing developer tools for the app platform. Through her work as president of Dames Making Games and member of the board at the Toronto Media Arts Centre, she is devoted to supporting and educating artists interested in software and electronic arts.

“I don’t always do the best job figuring out how to make this space [for connecting with collaborators], so I try to organize my schedule so that I have large swaths of time dedicated to more involved artistic projects.”

Stacco Troncoso & Ann Marie Utratel, If I Only had a Heart: A DisCO Manifesto (2019)

“In recent years, artists have more forcefully expressed their discomfort and outrage at the bankrolling of institutions by companies directly involved in climate change, human rights abuses, and other atrocities—motivated, in no small part, by moral and ethical concerns that big businesses are trying to effectively rehabilitate their public images by associating themselves with altruistic things like philanthropy and the arts.”

At the Digital Economies Lab workshop in Ottawa earlier this year, the group of assembled artists were asked whether they had ever participated in an event bankrolled by a military defence contractor. To an outsider, the question might sound like a joke. But the reality is that the art world is rife with wealthy corporate donors and philanthropists who make their millions, even billions, from work that many might consider morally or ethically fraught.

The shift to a corporate-sponsored art world has been underway for decades now (a story in The New York Times way back in 1985 looked at the then-emerging trend. But in recent years, artists have more forcefully expressed their discomfort and outrage at the bankrolling of institutions by companies directly involved in climate change, human rights abuses, and other atrocities—motivated, in no small part, by moral and ethical concerns that big businesses are trying to effectively rehabilitate their public images by associating themselves with altruistic things like philanthropy and the arts. The result: protests against the Sackler family, of oxycontin infamy, for gifts made to the Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others; protests against a member of the Whitney Museum’s board, for his stake in a manufacturer of tear gas; protests against oil company funding of the Louvre and the Tate; and protests against members of the MoMA PS1’s board for their connections to private prison and security firms.

“There are certainly moral and ethical quandaries to consider here, too—should an artist take money from a brand that’s been known to use child labour, or facilitated genocide in Myanmar?”

At the same time, corporations have begun to directly fund the artists themselves. As Samantha Culp wrote for The Atlantic in 2018, big global brands like Red Bull and Pepsi have stepped into fulfill the roles that wealthy patrons once used to fulfill. Well-known carmakers, shoe brands, soft drink conglomerates, and fashion houses have given artists lucrative money for branded work. For years now, some of the largest tech companies in the world have operated artist residencies. Google, one of the biggest proponents of machine learning, is funding artists to work with the technology. There are certainly moral and ethical quandaries to consider here, too—should an artist take money from a brand that’s been known to use child labour, or facilitated genocide in Myanmar?—but also valid concerns about the kinds of art that can and can’t be made with corporate money, and the kind of risks an artist can take. “It’s true that most branded projects don’t allow artists to approach sensitive topics such as sex, violence, or political critique—or meta-critique of the brand itself,” writes Culp.

There are certainly advantages and benefits to attaching one’s self to brand—financial, certainly, but access to resources, audience, and the heightened profile the relationship may bring. But not everyone can or should have to rely on corporate benevolence to make a living, nor should that be the primary source of income on which art institutions survive. We’re long overdue for a collective reckoning: a realization that artists are as much a part of a healthy society as anyone else, and that supporting their work is an indisputable public good. Some may still choose corporate patronage. But there should be other sustainable models for artists—for all workers, really—to make a comfortable living on their own terms, too.

“The fact that minority and community-based groups are ‘plagued by chronic financial difficulties’ is undisputed. But what isn’t being acknowledged is that these difficulties are the result of systemic economic inequality. It should come as no surprise that people in minority, disenfranchised, and rural communities don’t usually have access to millionaires and billionaires who they can cultivate as donors. Nor should it shock that these organizations will suffer if the public-funding system that was helping them build capacity, gain cultural legitimacy, and become sustainable is decimated.”

“I can’t even begin to fathom how liberating it would feel for my basic needs to be met without the obligations of full-time employment. It would free up untold energy and time and capacity that I could harness for all kinds of pursuits that are inaccessible to me right now.”

DEL Resident Emmanuel Madan is an artist who works with sound and technology and an organizer advocating on behalf of the Canadian media arts community. After training in electroacoustic music composition and work in the community radio, he devoted himself to an art practice that spans digital and electronic art, installation and performance, audio and video. He is a member of the collective [The User] and National Director of the Independent Media Arts Alliance.

“I think that BIPOC artists have less access to the kind of long runway that all artists need to try things out and develop. Honing a practice means being secure enough to fail, and even to fail multiple times. Without that safe space for failure, the pressure is just too high…”

Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2017)

“Funding disparity is not new to those working with POC-serving organizations and artists of colour seeking support and resources. In his book Many Voices, Many Opportunities (1993), historian Clement Alexander Price argues that in the United States, art produced by artists of colour is seen as relevant only to individuals and communities of color, while white European art is perceived to have universal relevance, reflecting the human experience at large. This prejudice is rooted in a long history of Western imperialism, slavery, and continuing systemic racism, which results in segregating the work of artists and arts organizations of colour. Community stakeholders point out that folk, urban, and traditional arts are often seen as distinct from contemporary art. This limited framing further restricts the funding pool for artists of colour.”

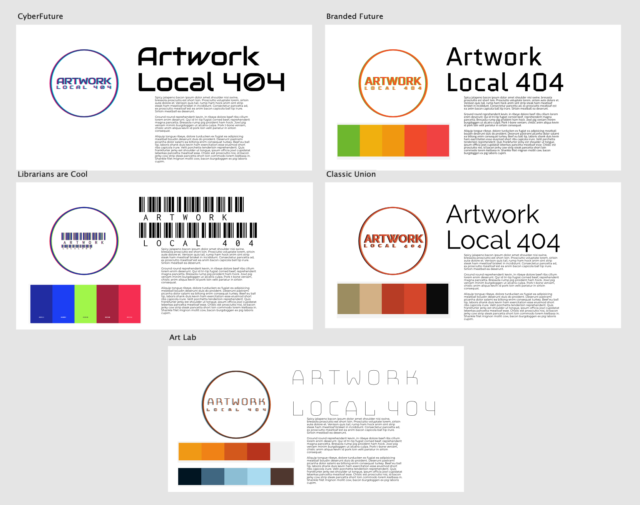

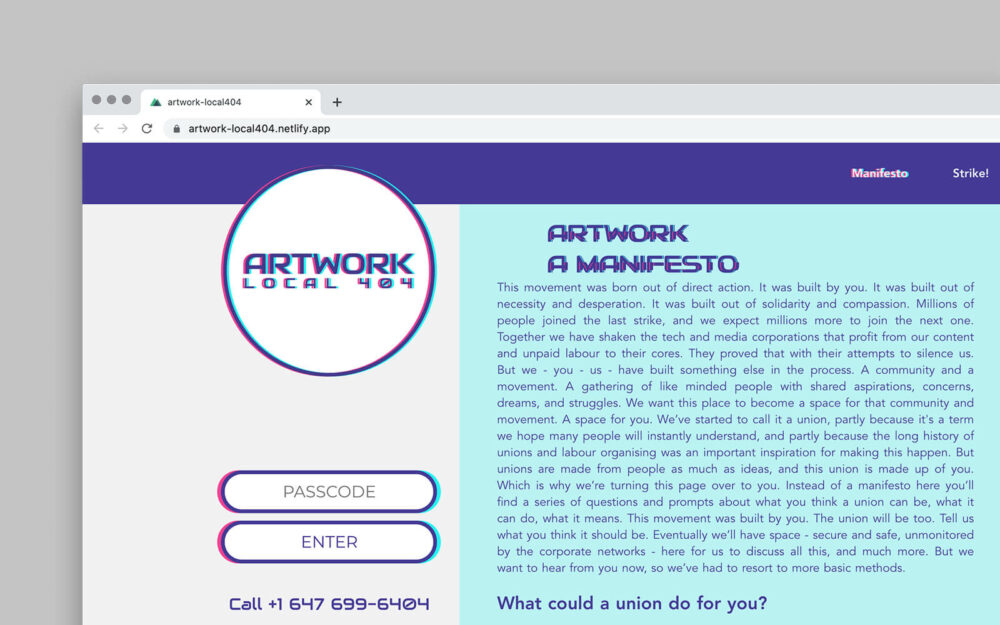

DEL Pitch: Artwork Local_404

“We want to make sure our freak flag flies, it’s a safe space for a diversity of thought experiments. We’re making space to explore what a union could be tomorrow, beyond the confines of the type of union we could build today.”

Outline:

Artwork Local_404, a speculative union, is meant to achieve a collaborative envisioning of what a thriving union could look like for artists. In this project we will explore how we can transform artists’ ability to take collective action so that artists are more successful and have productive inter-community relationships and knowledge sharing.

These speculations create an open way for us to collectively brainstorm what a different kind of Union could be. We want to make sure our freak flag flies, it’s a safe space for a diversity of thought experiments. We’re making space to explore what a union could be outside the confines of the type of union we could build today.

Team:

Izzie Colpitts-Campbell, Lee Jones, Emmanuel Madan, Tim Maughan

01 – Reference

Unionization in the creative sector is not a new idea. In New York in the aftermath of the Great Depression the Artists’ Union formed (founding members included Phil Bard, Boris Gorelick, Max Spivak, and Mark Rothko and Getrude Greene later joined). Initially a lobby for unemployment support, the union’s advocacy expanded to picketing the Whitney Museum and the municipal art projects office for economic relief and fair compensation.

02 – Preview

In our conversations we’ve discussed the idea of a union as a notion of transparency, a set of values, an automated entity, a dataset, an artist’s statement, and an overarching politics; these are early concepts for our speculative union’s logo and branding.

03 – Collaboration

Like everyone, the Artwork Local_404 team collaborated through Zoom in 2020. Here Emmanuel, Tim, and Lee mug for their webcams while Izzie plays director.

“In participatory practices nothing about us without us is one of the most important ideas to keep front and centre. What this means is listening to what folks need and getting their direct input rather than making assumptions about what their needs are.”

DEL Resident Lee Jones is a PhD student at the at Creative Interactions Lab at Carleton University. In her research, she uses participatory design and creates easy-to-use toolkits so that individuals can build prototypes and have a say in the direction their technologies go in. In her current project, she is developing a toolkit for prototyping wearable e-textiles.

“If I didn’t have to worry (as much) about making money I would be able to focus more. I notice my work improves dramatically when I’m really focusing deeply on one thing at a time. But due to my income sources being scattered, it means that my time and my thoughts are spread in many directions.”

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (2019)

“I have often wondered: when we talk of ‘social practice’ or ‘socially engaged art’, where and when do we start talking about social change? [Artist Gregory Sholette] criticises the genre of social practice for making ‘the social itself a medium and material of expression’, rather than a malleable process in which to take action. This is precisely the challenge to artists and activists, however they self-identify, facing today’s set of political, social and environmental challenges: not merely to make art about the political, or even within the social, but to make art that can radically alter the social and political possibilities presented to us.”

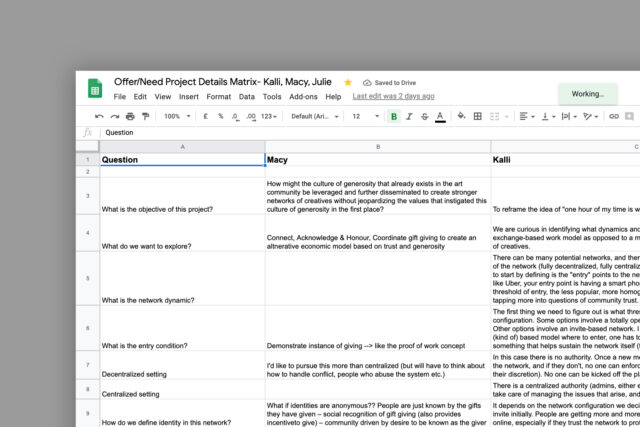

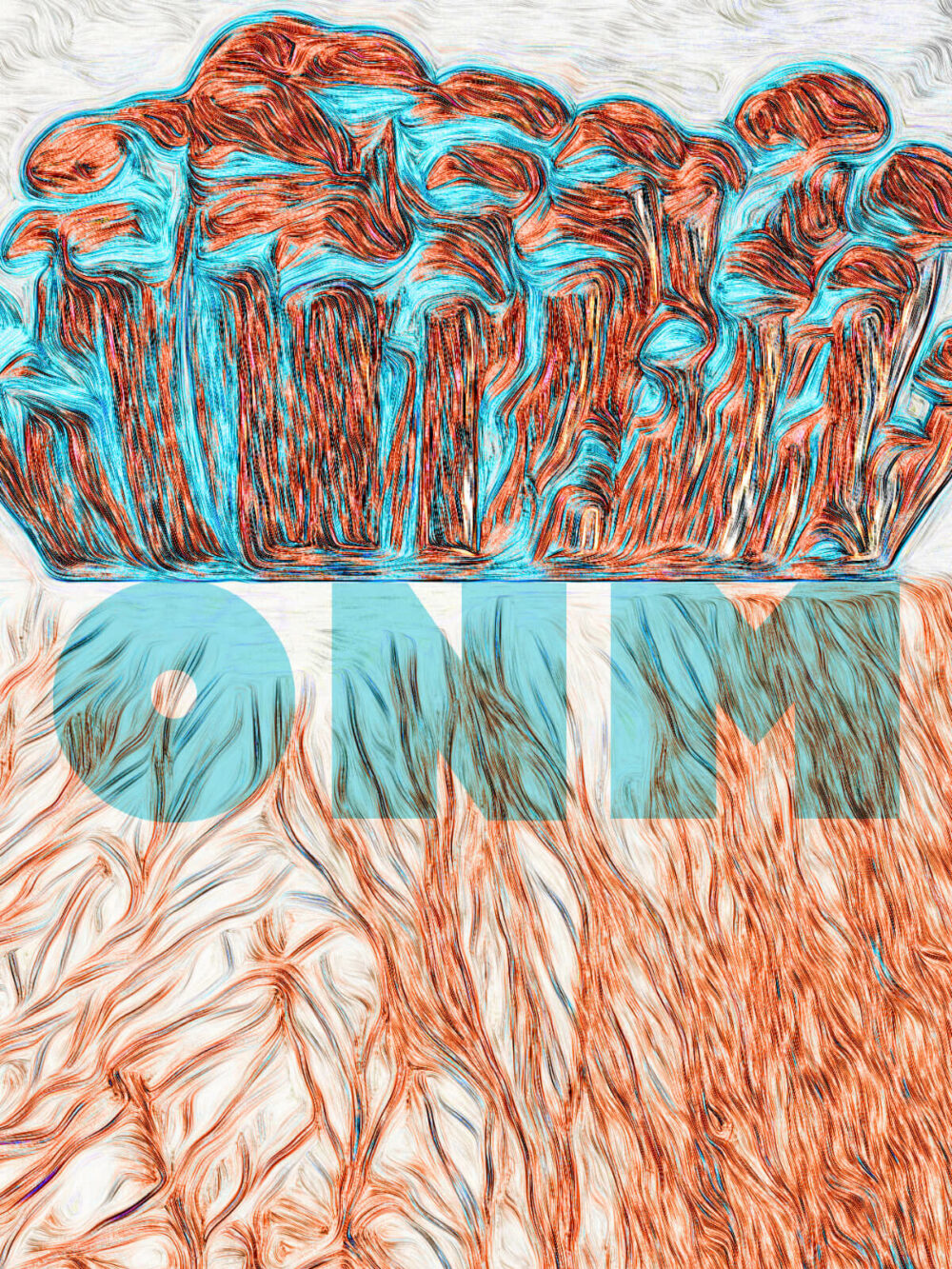

DEL Pitch: Offer Need Machine (O/NM)

“Members of this network volunteer time, and can in exchange receive time from another member. The intention is to create a system where artists can prosper by using both their creative and professional skills in exchange for services from (or as a gift to) other artists.”

Outline:

We are prototyping a web-based network modeled by the gift economy, collective care, and ‘pay it forward’ principles. Members of this network volunteer time, and can in exchange receive time from another member. The intention is to create a system where artists can prosper by using both their creative and professional skills in exchange for services from (or as a gift to) other artists.

To join, one must commit to offer one hour of their time as an initial gift to the network. Through established care protocols, the person who accepted their offer will have had an implicit obligation to pay that hour forward to a third party. We anticipate that this giving and receiving will not be limited to reciprocal exchanges between two parties. Instead, it will spur new connections between the participants of the network, driving growth and diversity, and creating a culture of perpetual giving that is intended to guide us out of isolation.

Team:

Julie Gendron, Kalli Retzepi, Macy Siu

01 – Reference

Janet Cardiff’s 2001 installation Forty-Part Motet uses a network of voices that is both powerful as a whole and in segmented parts. Its strength comes from the integration of interactivity that allows the audience to reimage new connections. These surprise connections are what inspire us.

02 – Collaboration

Writing down answers to what we identify as key questions is essential in order to articulate what we are thinking. We often talk about a ‘grid’ of concepts–and a spreadsheet is the perfect way to put that in front of our eyes.

03 – Preview

A few sketches showing what our web-based interface could look like.

“‘It’s evolved to where we seek corporate funding for all our shows,’ said Richard Oldenburg, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. ‘It’s getting harder now, because there’s more competition and the shows are more expensive.’ Yet many people warn that this trend has eroded the quality of the art shown in museums across the country. The pressure on art museums to produce exhibitions that promote a positive corporate image, these critics say, has caused museums to shun challenging new art in favor of ‘safe’ shows with no overtones of debate.”

“I feel like the pandemic has taken us to a state of liminality, a curious but also disturbing ambiguity as we peer over a precipice—I would like to continue to dwell and imagine at this threshold.”

DEL Resident Macy Siu is an artist and foresight strategist who is driven by expression and empowerment tied to the hyphen of in-between spaces. As part of the Toronto-based foresight studio, From Later, her practice focuses on creating evidence-based experiential futures and speculative design towards driving conversations around possible inclusive futures. Macy has a background in fine arts with editorial and public relations experience in the art museum sector.

“I’m so curious [about young artists’ perspective]. What visions might they have, of futures where concepts of uncertainty, trust, distance, work, care, etc. are already so drastically different than the old world that nurtured my own ways of seeing?”

Institute for Applied Aesthetics, The Artist-Run Space of the Future (2012)

“The question ‘What if Nike is the new Medicis?’ began as an art-world in-joke about a decade ago, but has grown less absurd over time. With the diminishing impact of traditional advertising, companies are seeking new ways to capture the attention and goodwill of the public. In exchange, brands provide financial opportunities to emerging artists. ‘In some ways, the goals are a little amorphous,’ Natasha Degen, a historian of the art market at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, told me. ‘The lines are becoming very blurred between corporate social responsibility, philanthropy, and marketing.’”

“TRANSFER is operating on a different timescale than most galleries trying to turn a profit to keep their doors open. The gallery exists to help bring artworks into the world, but our motivation is never around selling work in the short-term.”

Kelanie Nichole is a technologist and exhibition maker based in Los Angeles, and the founder of the experimental media art gallery TRANSFER. Since 2013, she has worked to explore new modes of supporting and exhibiting “distributed” artworks (namely, artworks that exist in digital, networked, or virtual spaces).

“We are in the midst of a historic social justice uprising and wealth inequality is falling out of fashion. This will be the great unraveling of the artworld.”

Q: Given how precarious digital artmaking—and artmaking in general—can be, where should we look to for optimism that sustainable artmaking is possible?

A: The only optimism I find is in the streets with the Movement for Black Lives. We must actively dismantle the status quo and make space for others to re-seed new values around artistic labor and creation. We are in the midst of a historic social justice uprising and wealth inequality is falling out of fashion. This will be the great unraveling of the artworld. In the meantime, new subcultures and genres are rising, artists are finding autonomy in everything from independently run art schools, like Dark Study, to creating installations inside MMOs for new audiences, as exemplified by LaTurbo Avedon’s work in Fortnite. I believe divesting from the institutions which now have power–and which perpetuate white supremacy–is the true way forward. This will require all kinds of new organizing, and inversion of the values of the existing artworld around scarcity, wealth, and power.

“Spoiler alert: despite important efforts by many leading foundations, funding overall has gotten less equitable, not more. This means that cultural philanthropy is not effectively—or equitably—supporting our evolving cultural landscape.”

“The question of why we don’t value artists or their work the same way we do other jobs is not a new concern. But we seem to find ourselves in a unique moment where there is a real possibility of change.”

For months now, the global pandemic has meant I’ve spent most of my days at home. With nowhere else to go, and only so much to do around the house, I’ve been consuming movies, TV shows, books, and games far more than usual. When there’s little to separate work from leisure, save moving from desk to couch, I’ve eagerly looked to the work of artists to keep me sane. The irony, of course, is that the same artists helping many of us fill our days—while we’re comfortably paid to work from home—are among some of the pandemic’s hardest hit.

For the CBC, Amanda Parris wrote about the pandemic’s dire impact on artist incomes. In Canada, where the arts and culture industries contribute billions of dollars to the country’s economy, the median artists’ income is well below the poverty line. The pandemic has only made matters worse. “Lockdowns around the world have forced tours, performances, book launches, festivals and film productions to cancel,” Parris writes, calling on all of us to finally “stop devaluing artists’ worth” and show them the support they deserve in our post-COVID-19 world.

And make no mistake, this is a societal concern. In times of crisis, “artists are expected to reinvent themselves, turn to crowdfunding, and hustle their way out of their predicaments,” wrote Miranda Campbell for Jacobin in 2015. “But we cannot crowdfund our way to broad public support for culture or to more sustainable approaches to cultural production. We need to move from narrating individual struggles to discussing community-wide challenges and collective solutions.”

“While governments were quick to talk about bailing out cruise operators and airlines, what does it say about art’s value to society that we didn’t move as swiftly or generously to bail out artists, too?”

The question of why we don’t value artists or their work the same way we do other jobs is not a new concern. But we seem to find ourselves in a unique moment where there is a real possibility of change. Max Haiven has argued that artists reeling from the pandemic share a common cause with other undervalued workers—from sex workers to restaurant servers—who have not benefited under capitalism. “Artists should in this moment be joining radical and ungovernable movements to demand, at very least that the emergency responses of the pandemic, which removed the economic coercion of capital, be extended widely and forever: basic incomes, rent suspensions, free high-quality public services, the nationalization of critical infrastructure, and more,” Haiven writes.

Numerous studies in countries around the world have shown the cultural, economic, and educational value that the arts and artists bring. While governments were quick to talk about bailing out cruise operators and airlines, what does it say about art’s value to society that we didn’t move as swiftly or generously to bail out artists, too? In the world we’ll build next, it can happen—if we want it to.

“The engine of Roosevelt’s arts funding was the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. It financed roughly 2,500 murals, 18,800 pieces of sculpture and 108,000 easel works. Thousands of original poster designs were created to advertise local zoos and library book talks or encourage people to get tested for syphilis and report dog bites.”

“Often when I’m pressed for time I switch to the ‘let’s create something’ mentality rather quickly. I would love to have as much time for meandering research, ideation, prototyping, making and polishing processes as possible.”

DEL resident Kalli Retzepi is a designer and technologist, and a grad of the Media Lab at MIT. She uses technology, design and images in order to explore the politics of digital interfaces, the narrative of the user and to imagine new metaphors for the Web.

“A Giant Bumptious Litter: Donna Haraway on Truth, Technology, and Resisting Extinction” (Dec 2019)

“Before this lockdown even began, artists in Canada were already facing a multitude of challenges…. Recent cuts follow a national trend where support for the arts is largely deemed elective. It is often one of the first areas on the chopping block when governments want to balance budgets. Artists are constantly forced to prove their value and worth to governments and voters. This lockdown should be a wake-up call to all of us who are leaning on these creatives now: arts and culture needs to be an unwavering national priority.”

“The best way to fund your artistic practice is to organize it like a business, and to fully accept that responsibility. For that reason, most of our interventions take on an emotional tenor that quickly bleeds into economic or legal concerns.”

Evan Kleekamp is a writer and researcher living in Los Angeles. They are the research director of NOR Research Studio, a consulting service that specializes in artist career development. They are also Operations Director for Study Hall, a 5,000 member strong community and knowledge sharing resource for media workers.

Ultimately, we encourage people to professionalize, even if it’s just to understand the emotional discomfort that professionalizing entails. The best way to fund your artistic practice is to organize it like a business, and to fully accept that responsibility. For that reason, most of our interventions take on an emotional tenor that quickly bleeds into economic or legal concerns. Funding your artistic practice requires fluency with conventions such as contracts, and you can’t properly advocate for yourself within a contract if you don’t understand your material and personal value. Running a successful business also means recognizing that we sometimes need formal structures that will stimulate us into parenting ourselves.

“When one of our clients manages to sell their first work or discover that their work in another medium is financially viable after years of stress and confusion, that motivates us to keep going.”

As the quote you’ve highlighted suggests, this comes from years of doing our work on ourselves and confronting painful moments in our personal history. If a client managed to get $25,000 in funds but they were too paralyzed by self-doubt to spend it on their practice, I wouldn’t be able to consider that a success. Similarly, when one of our clients manages to sell their first work or discover that their work in another medium is financially viable after years of stress and confusion, that motivates us to keep going. When we have clients who get to the finalist round of a grant application, that’s a strong argument that nothing was wrong with their work—they just needed more adequate framing and accomodation.

“There is a sense that a parallel art market is emerging that comprises a new set of artists and collectors. But the $69 million question is whether this is going to become another hype cycle like virtual reality was in 2016, or Net art before the dot-com bubble burst in 2001.”

DEL Reflection: Jeremy Bailey

“I think what we’re seeing right now is a golden age of artists cooperating to own the means of production. That would be the one thing I’d love to leave the audience with: this idea that to be a true anticapitalist you appropriate the means of production. That’s what I’ve always pursued—and queer it, if you can.”

Liner Notes:

Taking stock as DEL begins to wind down, “Famous New Media Artist” and Steering Committee member Jeremy Bailey and Artengine’s Ryan Stec muse over the persistant mythologies around the comingling of art and money that continue to cloud perceptions of aura and value—especially now, as we struggle to assess a world full of freshly-minted NFTs. Speaking to “the big C” of capital—the strange anxities it provokes within the art world—the duo dispell the romantic notion that money is a blight or intrinsically ‘impure,’ and pragmatically discuss what art plus capitalism (plus a critical agenda, of course) looks like.

These quotes, notes, and references are highlights from a 40-minute conversation that took place between Jeremy & Ryan in Spring 2021. Click through below and watch the entire exchange.

01 – Lean Artist

“The world’s first seed accelerator for artists,” the Lean Artist initiative has run at A/D/A Hamburg (2016, image) and MCA Chicago (2018). Adopting the startup world’s agile approaches and the minimum viable product model, 10 creators have worked with Jeremy to conceive and monetize projects.

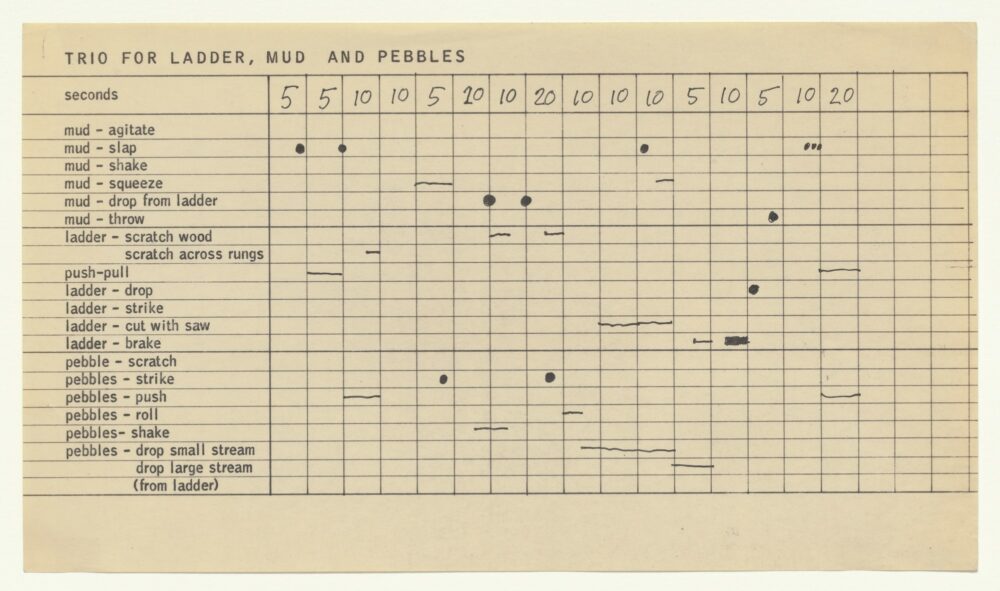

02 – Fluxus

The Fluxus sentiment that art is not for the bourgeoisie is cited as being crucial. Inspecting the score for George Maciunas’ performance Trio for Ladder, Mud and Pebbles (1964) evokes that movement’s inherently messy, visceral, and embodied nature—a full-on rebellion against the elitist positioning of ‘art as rarified commodity.’

“Ultimately, what is likely best for artists is what is best for all workers: universal high quality free public services and the abolition of the wage-discipline of capitalism. These demands seem possible surprisingly today and are in a strange way an actually existing fact in the emergency. If artists make common cause with others, we might be able to preserve and extend these, and so abolish capitalism as such.”

DEL Reflection: Artwork_local404

“Unions are about solidarity and creating a presence that is greater than one person—knowing that somebody has your back. We are arguing for that within the arts; and the idea, that, you know, if someone messes with you they’re messing with a collective. That’s what a union is about, really, in an old school labour sense.”

Liner Notes:

In three conversations with Artengine’s Ryan Stec and Remco Volmer, DEL residents Emmanuel Madan, Tim Maughan, and Izzie Colpitts-Campbell outline the thinking behind Artwork_local404, a speculative union for cultural workers they produced along with collaborator Lee Jones. Drawing in equal parts from the history of twentieth-century blue-collar organizing and familiar frustrations of being human grist in the social media mill, they make the case for using “solidarity and sharing to fight back against divide and conquer tactics.”

The project emerges from the team’s experience authoring novels, videogames, and installations; working in commercial entertainment and the art world; teaching, and creating support infrastructure for creators and artists (i.e. Izzie’s work for Dames Making Games, Emmanuel with the Independent Media Arts Alliance). This experience also shapes the trio’s insightful interviews on labour—and the power of withholding it, to force change

These quotes, notes, and references are highlights from three hour-long conversations that took place between Emmanuel, Izzie, and Tim with Ryan and Remco in Spring 2021. Click through below and watch the interviews in their entirety.

01 – Strike!

“We will no longer stand for being just the content between adverts!” To underscore the power of withholding labour and the fact that social media content has tangible value, the group proposed a 24-hour ‘content strike’ on social web services for May 12, 2021. Image: Striking dressmakers, with placards demanding wage hikes, take a break in a diner (~1955), from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives.

02 – Call Them Maybe

Harkening back to an era of simpler connectivity, Artwork_local404 deploys a touch-tone telephone interface. Art workers call in and are prompted to answer questions about labour and work conditions.

03 – artwork-local404.netlify.app

Complementing their retro interface, the group published a web manifesto that argues for collective action within the arts. Rather than simply arguing for organized labour, they imagines the substance of how that union might work, identifying what organizational cues it could take from contemporary platforms and media.

“So many of the problems that artists face are related to power, to who can make decisions, or holds the purse strings. And so much of that power lies in decisions made behind closed doors, and only allowing artists glimpses of what happens, what affects them directly.

What if a union could blow all that open? What if it could use our solidarity and sharing to fight back against divide and conquer tactics? What if it named and shamed? What if it was less Glassdoor and more WikiLeaks? What if it published emails and recorded phone conversations?”

“If we can re-create the plumbing of the music industry, then all those middlemen have to compete with code. I would be really scared if I were an incumbent player, because they have no idea what’s coming.”

DEL Reflection: The Artist’s Almanac

“One of the prompts that Alisha and I give is to ask people to go as far into the future as it takes for them to have their needs met. Some people say ‘in 10 years I’ll have X, Y, and Z.’ For others, it’s ‘in 1,000 years, X, Y, and Z.’ And some say ‘in 10,000 years, after the super volcano erupts and wipes out everything, and reanimates the earth—then we’ll talk.’”

Liner Notes:

In a conversation with Artengine’s Ryan Stec, DEL resident Suzanne Kite describes the thinking and process that informed the Artist’s Almanac. While all DEL projects were impacted by the pandemic, Suzanne’s was transformed by its strains. Pivoting from her initial plan to develop a resource for racialized artists, her almanac became a container for a broader conversation about care and support. In addition to Artengine, she enlisted Concordia University’s Feminist Media Studio and the HTMlles Festival to organize a consultation with a 20 artists and cultural producers.

In the wrap-up interview, she dives deep into her thinking around the telescoping time scales required for healing across generations and how futurity is relative. She also takes care in articulating the difference between research-creation (‘producing’ knowledge) versus consultation with elders or stakeholders, and, more broadly, ruminates on her thinking around how to build bridges of solidarity and support between marginalized communities.

These quotes, notes, and references are highlights from an hour-long conversation that took place between Suzanne and Ryan in Spring 2021. Click through below and watch the full interview.

01 – Facilitators

Suzanne enlisted a team of A-list facilitators to develop the Almanac. Alisha B. Wormsley, Jas M. Morgan, and Lupe Pérez, brought experience in education and community organizing from Afrofuturist, Indigenous, LGBTQ2S+, and design justice circles, to help structure and coordinate the community consultation.

02 – A list of lists

A ‘list of lists’ was compiled to take stock of resources for collective care that were already circulating. In addition to Missing Justice (image), which raises awareness about violence and discrimination against Indigenous women, some of the Almanac references and precedents include Adrienne Huard’s writing, Afronautics Research Lab, Black Feminist Study, CyberFeminism Index, Pirate Care, Queer.Archive.Work, and trans-resist.

03 – The Virtual Whiteboard

Since meeting face-to-face was impossible, workshop participants gathered around virtual whiteboards. Instead of a running headlong into design sprint, they interrogated first principles, asking questions like ‘how does the almanac respond to community needs?’ (image), and ‘what consultation should be done?’

“In order to fuck with profit, you have to understand your own role in the circulation of capital. You have to confront how profit is produced. In this way, sabotage reveals where value comes from: the worker.”

DEL Reflection: Artists as ‘Alternative Consultants’

“Some people like that game, but I was never a fan; it feels like we should have other games that we’re allowed to play. I’ve got nothing against the hustle, nothing against the start-up world. It’s when those moral positions become hegemonic for everywhere else and start to define everything, like access to water and knowledge—then they become problematic.”

Liner Notes:

In a conversation with Artengine’s Remco Volmer, DEL resident Jerrold McGrath zooms out from the art world as a site of production, and considers opportunities for care, growth, and revitalization. Crucially, he articulates where existing hierachy needs to be dismantled and cleared, to make way for new formations. Drawing on his experience at the Banff Centre, Jerrold arrived at DEL with a strong desire to help artists out of their (prescribed) lanes—to bring their knowledge and expertise to other milieus; this desire has only grown bolder with the failure of so many vital infrastructures during the pandemic.

In his DEL ‘exit interview’ Jerrold mounts a sustained critique of the “scarcity mindset” that is rampent across the arts, and nimbly maps noncompetitive alternative framings. As per his earlier ruminations on mycology, he draws extensively on metaphors and teachings derived from natural systems (freshwater, forest management, etc.) as a way to re-think structure and support.

These quotes, notes, and references are highlights from an hour-long conversation that took place between Jerrold and Remco in Spring 2021. Click through below and watch the full interview.

01 – Ferment AI

An outgrowth of his work with Ukai Projects, Jerrold launched Ferment AI, a newsletter about art and AI last spring. The tone of the dispatches blends playful optimism (deeply engaging AI’s generative potential) and pragmatism. “If the idea of progress—the promise of a better future and ever-faster ways to get there—is no longer valid, then AI offers some sense of control, at least to avoid the worst disasters.”

02 – Rapid Response

Medical face shields, masks, respirators—the onset of the pandemic caused shortages worldwide. Seeing an opportunity to put strategic thinking into action, Jerrold teamed up with 80 peers to address inequity in resource shortfalls through Maitri Platform. “We organized the work around mycelial structure” says Jerrold. Outcomes include “turning garment factories into PPE production in India, repurposing sleep apnea devices into non-intensive breathing support in the Global South, and fundraising support for Indigenous women-led COVID projects across the U.S.”

“Barter systems would indeed make it difficult for an economist to eat lunch. Would a restaurateur exchange his goods for a lecture on monetary policy? Perhaps not, and the meal goes unsold and the economist goes hungry. Thankfully, the economist has students to whom he can sell his knowledge for dollars, which then function as a medium of exchange with which he can purchase his meal.”

DEL Reflection: the Offer/Need Machine

“Our hope for the Offer/Need Machine was that the values that exist within the culture of generosity amongst creators could be more widespread, better leveraged, and become their own knowledge system. We were drawing inspiration from solidarity economy principles and gift economy practices to think about exchange where it’s not quid pro quo or transactional, and more of a kinship structure where others support you and have your back.”

“This project is also a reflection of the changing definition and reality of what it is to be a professional artist. It is near impossible to make a living solely from one’s individual artistic production, and so almost all artists are many things. This project will leverage the multiplicity that exists within individuals and create a larger more resilient network of cultural producers.”

Liner Notes:

Spanning four conversations with Artengine’s Ryan Stec, DEL residents Macy Siu, Julie Gendron, Kofi Oduro, and Kalli Retzepi outline the thinking behind Offer/Need Machine (ONM), a decentralized network of reciprocity where artists, designers, and art organizations exchange “one-hour gifts” of knowledge and expertise to support each other outside of traditional commerce.

Nurtured within the Digital Economies Lab, in spring 2021 the ONM team secured funding to develop a prototype through a Canada Council for the Arts Digital Strategy Fund grant, which the team will work on through fall 2022.

In these interviews, we hear varying notions of care from across the team—and how ONM could remedy the pervasive problem where artists of limited means are stifled because of a lack of crucially needed expertise.

These quotes, notes, and references are highlights from conversations that took place between the ONM team and Ryan Stec in Spring 2021. Click through below and watch the interviews in their entirety.

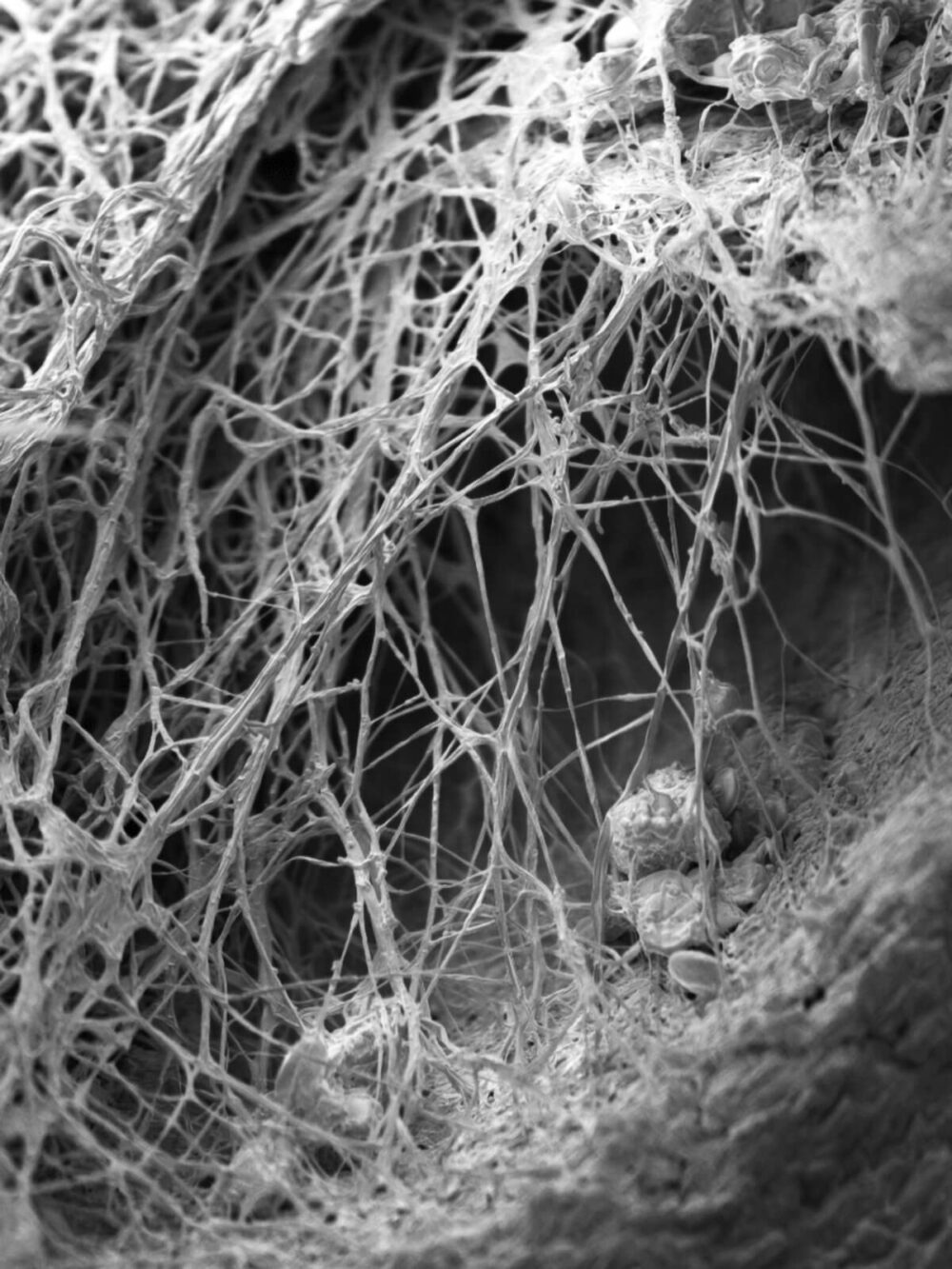

01 & 02 – Mycellium as Muse

“Initially the project stemmed from an obsession with mushrooms and mycelium networks and how natural systems are able to detect and transfer resources,” notes Siu in her interview. From day one, the ONM team was looking to how nonhuman species communicate, sense, and share for inspiration. This thread continues to the present day, as evidenced by the distinctly mycelial ONM frontispiece image by Oduro, the team’s Creative Director.

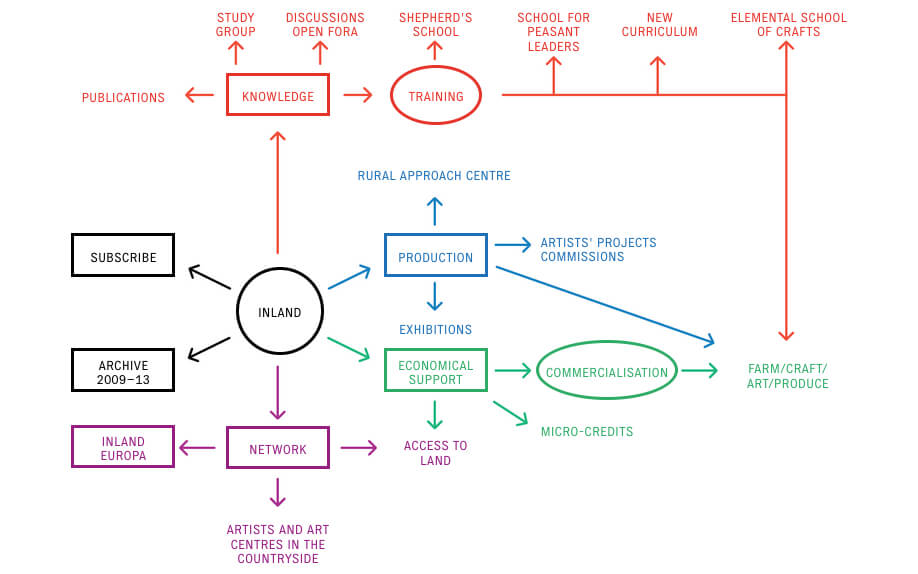

03 – Knowing the Field

ONM may be rooted in theoretical models of collectivity informed by biological systems, but the team did their homework in positioning their project. As part of their grant application, they conducted thorough market research, studying resource sharing spanning a Blockchain care protocol, to an item swap platform, to a European collective focused on agricultural resource sharing (Image: Inland, organizational diagram).