← Explore

Research: Alternative Exhibition Spaces

“Why only look at exhibition history as evidence of an artist showing their work? Instead, I suggest we broaden this idea of showing work to sharing work.”

“Why only look at exhibition history as evidence of an artist showing their work? Instead, I suggest we broaden this idea of showing work to sharing work.”

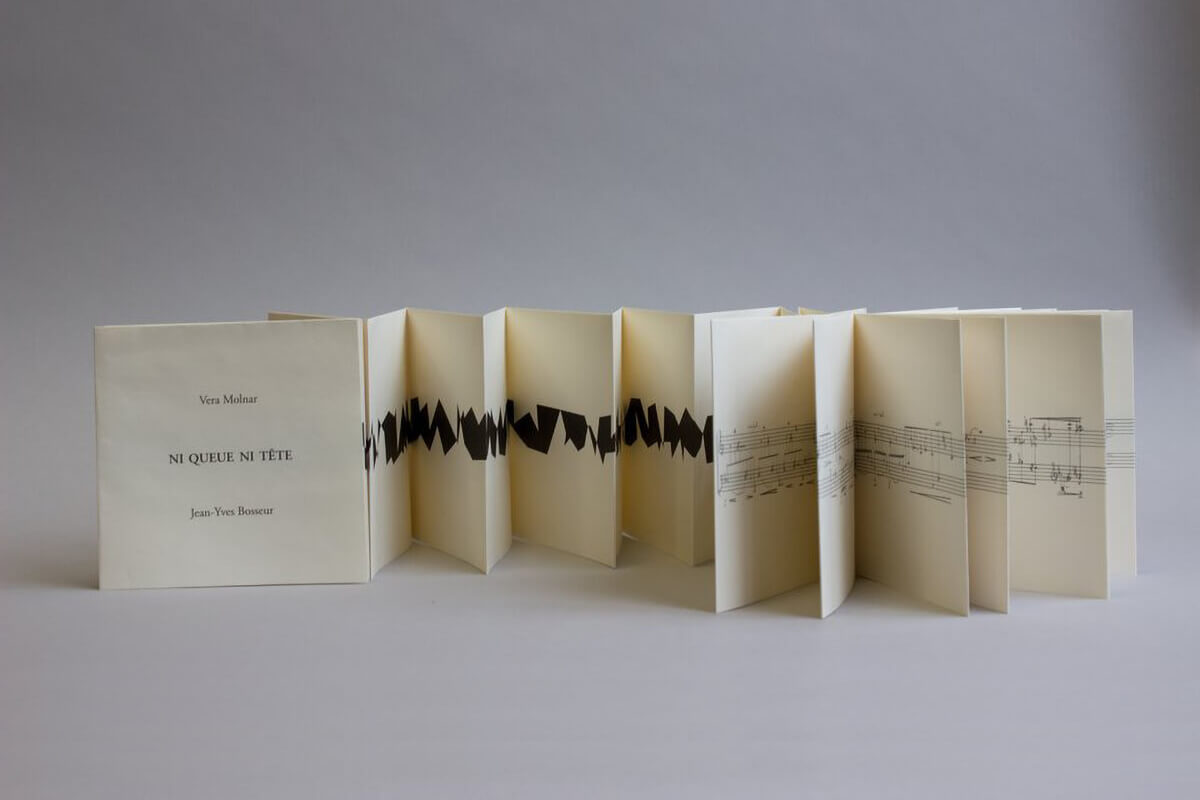

Vera Molnar, Ni Queue ni Tête (Neither Tail nor Head) (2014), 15 x 15 cm (folded)

A collaborative project bringing together a visual work by Molnar, a composition and text by Jean-Yves Bosseur, and performance by Pascal Dubreuil. Edited and published by Couleurs Contemporaines and Bernard Chauveau. The work is housed in a custom-made portfolio box containing Molnar’s six meter long folded artwork, printed on 90-gram Acroprint Edizioni paper; a musical score partition booklet by Bosseur; and a CD of Dubreuil’s performance.

A collaborative project bringing together a visual work by Molnar, a composition and text by Jean-Yves Bosseur, and performance by Pascal Dubreuil. Edited and published by Couleurs Contemporaines and Bernard Chauveau. The work is housed in a custom-made portfolio box containing Molnar’s six meter long folded artwork, printed on 90-gram Acroprint Edizioni paper; a musical score partition booklet by Bosseur; and a CD of Dubreuil’s performance.

“Enter the alternative spaces in which Molnar’s work reached audiences: informal research groups, festivals, academic journals and conferences, art magazines, and self-published artist’s books.”

The usual narrative around Vera Molnar’s work is that she didn’t exhibit her work until the mid-1970s, and even then, only sparingly. It is true that she didn’t focus on exhibiting and building relationships with galleries until the 1990s, especially after her husband passed away. Whether her husband was the reason why she didn’t exhibit much before this is up for debate, but let’s save that for another day. Instead, I want to ask a different question: why only look at exhibition history as evidence of an artist showing their work? In today’s research note, I suggest we broaden this idea of showing work to sharing work. In other words, what were the more informal contexts in which Molnar shared her images or her ideas? We are going to peek at some of the alternative spaces in which Molnar’s work reached audiences: informal research groups, festivals, academic journals and conferences, art magazines, and self-published artist’s books.

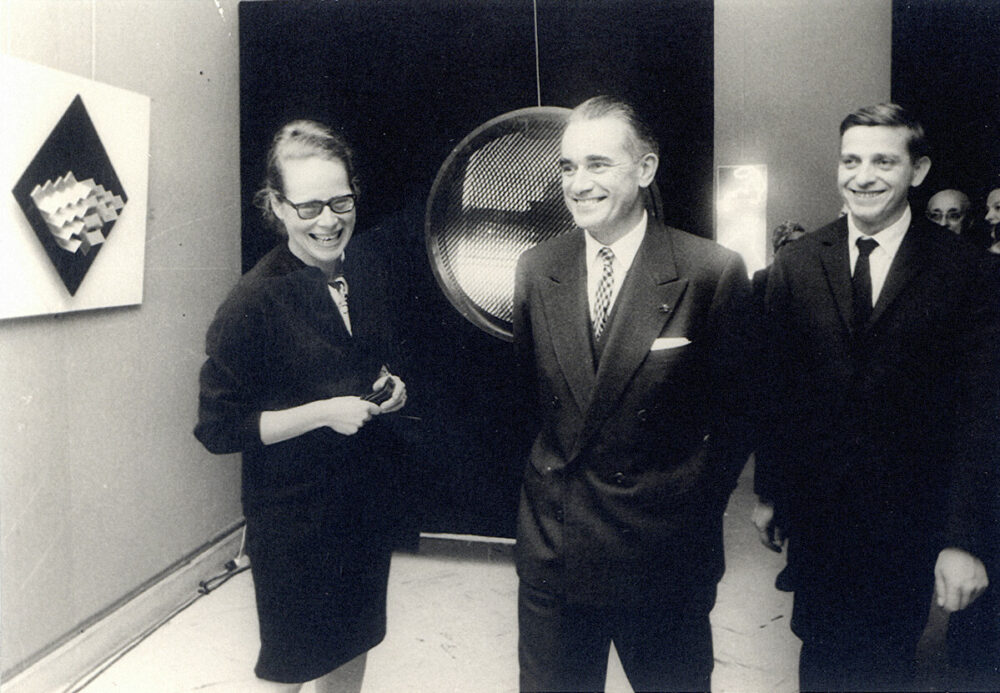

In 1967, a year before she first accessed the electronic computer with the help of Pierre Barbaud, the Molnars co-founded the group Art et informatique (Art and computing) at l’Institut d’esthétique et des sciences de l’art (Institute for aesthetics and the science of art) at the Sorbonne in Paris, where François Molnar worked as a researcher. The group mainly consisted of music composers, including Barbaud and Janine Charbonnier, but also included poets like Jacques Mayer, who wrote in the parameter-driven Oulipo style made famous by novelist George Perec. Vera Molnar was the only painter in the group; in fact, despite their near-identical names, Art et Informatique would have little contact with the Groupe Art et Informatique de Vincennes (GAIV), formed at the University of Vincennes across town in 1969. As Molnar recalls, the Sorbonne group met weekly to discuss their works-in-progress and the more theoretical stakes of computing for the field of aesthetics. As these conversations gained momentum, the members of Art et informatique shared their work with broader audiences at events like the SIGMA festival in Bordeaux, which showcased contemporary intersections of art and science. While François Molnar had already participated in the first edition of SIGMA in 1965, co-organized by Michel Philippot (the composer who inspired Vera Molnar’s ‘machine imaginaire’) and Abraham Moles (who developed the field of ‘information aesthetics’ in France), Vera Molnar did not formally participate in the festival until 1973, when the festival was titled “Art et ordinateur” (Art and computer). Here, she gave a talk titled “L’Oeil qui pense (The thinking eye),” which she borrowed from the notebooks of Paul Klee. She also designed the festival posters as well as the catalogue for the exhibition “Contact,” in which her computer plotter drawings were shown alongside computer graphics made by Herbert W. Franke, Kenneth Knowlton, Manfred Mohr, Frieder Nake, and the GAIV artists, among many others.

“In response to her 1975 Leonardo text ‘Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer,’ Molnar received quite a bit of fan mail. She replied by mailing out photocopies of her artists’ books.”

Vera Molnar (left) and François Molnar (right) with Jacques Chaban-Delmas, then mayor of Bordeaux, at the first SIGMA festival in Bordeaux, 1965 (Molnar archives, used with permission of Vera Molnar)

(1) Vera Molnar, Cover for Computer Graphics and Art, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Feb 1977; Molnar archives)

(2) Vera Molnar’s article in Leonardo, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1975: 185-189) (Molnar archives)

(3) Vera Molnar’s work reproduced in Abraham Moles’ book Art et ordinateur (Casterman, 1971), likely the earliest circulation of Molnar’s images in print. Note that the image reproduced (left) is not a plotter drawing, but a collage based on a computer-generated image.

(2) Vera Molnar’s article in Leonardo, Vol. 8, No. 3 (1975: 185-189) (Molnar archives)

(3) Vera Molnar’s work reproduced in Abraham Moles’ book Art et ordinateur (Casterman, 1971), likely the earliest circulation of Molnar’s images in print. Note that the image reproduced (left) is not a plotter drawing, but a collage based on a computer-generated image.

Vera Molnar’s artist book Ni Queue ni Tête (Neither Tail nor Head) (2014) on view at Beall Center (table)

It was in these liminal spaces between art and science that Vera Molnar’s work first reached an international audience beyond the Sorbonne computer lab. Throughout the 1970s, her images circulated in American periodicals including Computers and Automation, (later renamed Computers and People) and Computer Graphics. These black-and-white reproductions were flanked by technical specs––what machines she used to make them––as well as short anecdotes from the artist. Molnar also penned longer articles for journals, perhaps the most widely distributed being the Franco-American journal Leonardo, edited by artist/engineer Frank Malina, which was published in English and thus had a wide Anglo-American readership. In response to her 1975 text “Toward Aesthetic Guidelines for Paintings with the Aid of a Computer,” Molnar received quite a bit of fan mail. She replied by mailing out photocopies of her livrimages, her artists’ books, including Love-Story and Out of Square (both 1974), which she referred to in English as “computer picture books,” until she ran out. Molnar self-published her early livrimages, cutting and pasting their accordion folds by hand, only later collaborating with printmakers and publishers (mostly notably Bernard Chauveau) to make higher-quality artist’s books, two of which are included in the Beall exhibition (Ni Queue ni tête, 2014 and Six millions sept cent soixante-cinq mille deux cent une Sainte-Victoire, 2012).

“Alternative modes of ‘exhibiting’ might have done things for Molnar that showing in traditional art venues couldn’t have: they brought her work to an international, more open-minded audience.”

I don’t mean to suggest that giving an artist’s talk at an academic conference, or publishing computer graphics in a specialist journal, are the same as gaining art-world recognition. Of course, these are quite different kinds of achievements. However, I want to suggest that these alternative modes of ‘exhibiting’ might have done things for Molnar’s work that exhibiting in traditional art venues couldn’t have. For one, they brought her work to an international audience, one that was perhaps more open-minded than the traditional museum-goer when it came to determining what counts as art and what doesn’t. Moreover, by printing her words alongside reproductions of her work, these print publications in particular worked to level the hierarchy between the artist’s theory and practice, placing them on equal footing. On the one hand, we could say Molnar had to be her own critic in the absence of art-world attention. But on the other hand, this gave her an advantage, as these venues provided more space for context and the artist’s own voice, allowing her to direct her own narrative.

(1) For more on Molnar’s Livrimages, see Vincent Baby’s text “Les Livrimages” (1999, in French)